Science, Bitches | Issue 20

Mind Control

Remember the Animorphs book series? With the slug-like Yeerks that got inside your brain and treated people like giant finger puppets? As much as I loved those books, I knew that my bitchy English teacher wasn’t really infested with a mind-controlling parasite – but some members of the animal kingdom aren’t so lucky.

Such as that unfortunate fish. Normally, he would stay away from the water’s surface, out of sight of predators; he would use his streamlined body and darker back to avoid drawing attention to himself. But on this fateful day, he’s doing the opposite – rising to the surface, splashing and exposing his reflective underside; the perfect target for a hungry bird. So why is he doing it? Because the trematode Euhaplorchis californiensis wants him to. This trematode, like many parasites, has a life cycle that is dependent on several hosts. Firstly, the larva swims around until it’s eaten by a horn snail. That snail is then a snack for our killifish, and while it’s being digested, the parasite makes its way along a nearby nerve and into the brain cavity. Here, it forms cysts, which make the fish shimmy like it’s the 90s – an easy feed for a shore bird. Once eaten, the parasite reproduces in the bird’s intestines and releases eggs in the poo. These eggs will be picked up by a snail, which will be eaten by killifish, and the cycle will re-start.

Think the killifish is alone in its peril? Think again. Spiny ants aren’t, by nature, particularly rebellious animals, so when a lone ant wanders off, you should be intrigued to know that she will travel to the underside of a north-facing leaf, about 25cm off the ground. Once there, she will bite the main vein of the leaf and stay there for the rest of her life – which won’t be long, since a giant fungal stalk will shortly erupt out of her head. This fungus is Ophiocordyceps unilateralis, and once it has eaten our ant from the inside out and given her what looks like some sort of avant garde hat, the stalk will explode, showering fungal spores over the rest of her colony. These newly infected “zombie ants” will climb to the underside of a north facing leaf, 25cm off the ground, bite the main vein ... I think you get the idea.

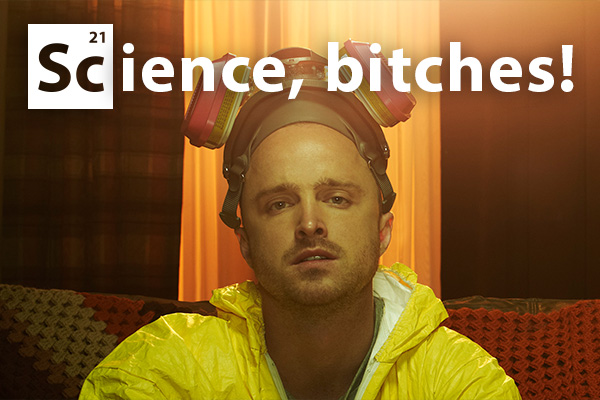

At this point, we’re not too hopeful for our mouse. Why does it stop being afraid of cats? Because Toxoplasma gondii wants him to be eaten. How does it do it? Mind control. Healthy mice have a strong aversion to cat pee, but infected mice will practically bathe in the stuff, allowing the parasite to make it to the next host, the cat. But remember when I said your English teacher wasn’t infested with brain parasites? Well, I might be wrong; about 25 per cent of New Zealanders have been infected with Toxoplasma at some point – if you’re healthy, there aren’t any symptoms, but considering that the effects persist in mice even after infection, it might explain why we like cats so much … That’s science, bitches!