The theme is the most overlooked aspect of any board game. When all of the game’s events, actions and individual components come together as parts of a cohesive whole, your response to the game as a player is similar to that of the characters you are playing as. Theming is hard to attain and maintain, and it is what sets a lot of modern board games ahead of the standard get-from-A-to-B format. Snakes and Ladders has no theming at all. Dead of Winter, by contrast, has theming like Harry Potter has helpful moral lessons: you don’t necessarily notice them, but they are a core part of what makes it an enjoyable experience.

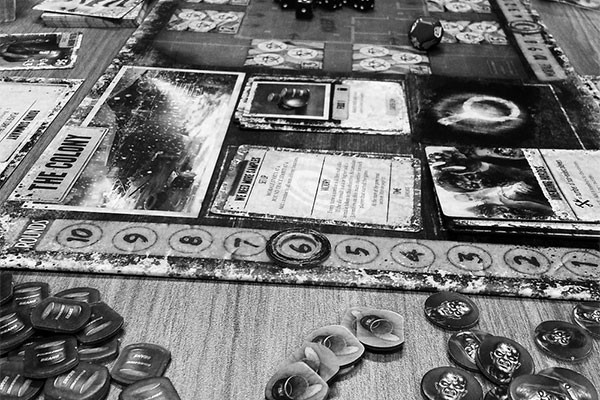

Dead of Winter is a zombie apocalypse survival game, which you would not expect to work in the board game genre. Each player controls a number of survivors, all of whom must work together to keep a safe compound free of zombies, maintain a healthy team morale, and ensure that supplies from six locations outside the compound are retrieved. Each game has one main objective; this can range from killing enough zombies to find a cure for the infection to emptying a location of all its supplies. You are forced to travel outside the compound, searching around for enough food to feed everyone. On top of this, everyone has their own private objectives. These cannot be shown to anyone else until the very end of the game. They may be honourable, such as needing to have a certain number of items in your hand by the time the game ends, or they may be betrayal cards that urge you to secretly work against all of your teammates. This adds a subtle layer of mistrust to the game; your lack of knowledge about your teammates feeds into your paranoia, and builds tension throughout the game.

The gameplay of Dead of Winter is essentially a series of spanners being thrown into the proverbial works. Aside from your main objective, you have a new crisis every round that must be resolved in order to avoid losing morale. Every turn, players are given crossroads cards, which are morale-testing objectives that are triggered if certain criteria are fulfilled. Every single time you move or fight zombies, you must roll an exposure dice which risks giving your survivor a wound, frostbite, or a zombie bite, the latter of which will instantly kill them and then spread to other survivors.

While many board games have the same level of difficulty throughout their duration, Dead of Winter tightens and tightens as it progresses. The more survivors you find out in the cold, the more food you have to find to feed them all. The more survivors are at a location, the more zombies will be attracted to those survivors. Every time a survivor dies, your team morale goes down. If your morale reaches zero, you lose. If you run out of rounds before you complete the main objective, you lose. If you can’t feed everyone, you will eventually lose. The closer your morale is to zero, the more heavily you are reminded of the fact that one bad exposure roll could kill everyone at a location.

One could perhaps criticise Dead of Winter for not being scary, which one might expect of anything zombie-apocalypse-related media. However, in a boardgame a scary atmosphere is borderline impossible to attain. Dead of Winter has no inherent pretensions of being scary, occasionally throwing in such joke events as racing mobility carts to raise morale, or choosing which ridiculous location to find a severed head in. Instead, Dead of Winter has an almost palpable tension that grows as the game goes on. The more your morale sinks, and the more the rounds tick on, the need to complete your objective grows in inverse proportion to your ability to feed everyone and stem the flow of zombies.

There is so much replay value in Dead of Winter, and not just because of how much content the game has. It’s rare to find a board game that is so broadly entertaining, so accessible to new players, and yet such a genuine challenge every time one plays it.