Patrick Lundberg Draft Copy

Hocken Gallery | Exhibited Until 4 April 2015

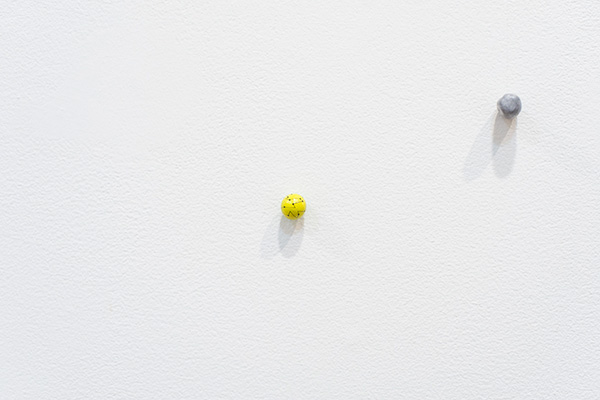

On entering the Hocken Gallery, however, a distracted viewer, or one with diminishing eyesight, may wonder where the art is at all. A closer inspection of the white surfaces is revealing. Arranged across the walls are small colourful objects like round, stationary insects. These globes of gesso, acrylic, pencil and varnish attached to the wall by hidden pins are arranged in six different instalments throughout the gallery, with large spaces between each instalment. In one room, for example, there are four creamy-white balls arranged at the intersections of the room’s walls. At first, they are almost indecipherable from the wall. But a closer look reveals small, speckled, colourful details.

The works that Lundberg has created for Draft Copy can be examined as individual art objects that occupy their own space and also as the shape that they create within their arrangement. This and the objects’ visual qualities show that Lundberg has used his time in Dunedin as 2014 Frances Hodgkins Fellow (previous fellows include Ralph Hotere, Jeffrey Harris and Seraphine Pick) to build on previously formed ideas.

While beautiful in themselves, the pin heads’ size is such that the viewer finds herself equally lost in the inbetween and the periphery. Suddenly, the rough white paint covering the walls and the bulk of the lights that illuminate the art from above (both staples of most gallery spaces) become noticeable and part of the work in a way that could never be achieved by framed paintings or stand-alone sculptures. The boundaries of the institutionalised gallery space are brought into question again in an instalment where one of the balls, like a dropped yellow lolly, is “lost” on the ground. For several minutes the viewer may consider going downstairs to inform the staff that the exhibition is falling apart. But, be warned, Lundberg is playing with her; forcing her to acknowledge her deeply held, supposedly natural, ideologies about how a gallery “should be”.

With space being one part of the conversation, art’s permanence (or lack thereof) is another. An interest of Lundberg’s, Sol LeWitt was a leader and one of the first artists of the postmodern era and advocated for an idea itself being art. LeWitt believed that the production of work could be delegated to others and still be able to be called his art. Draft Copy’s temporary nature invokes a similar idea. While Lundberg has created the art himself, the balls arrived at the gallery and will leave the gallery with no decided or definite layout. In their perpetual status as “drafts”, the balls are incomplete artworks in that they can always be rearranged; how they interact with the space and the viewer will also change accordingly.

While Lundberg’s final products are beautiful, it is when viewing his work as this idea of a draft or an incomplete process to be completed by the viewer’s interaction with the art that makes Draft Copy exciting; it partly relies on the viewer to make it engaging. This art is about ideas and, as LeWitt said, “The idea itself, even if not made visual, is as much a work of art as any finished product.”