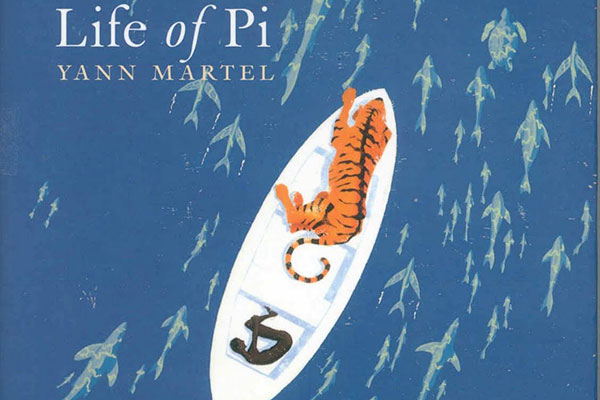

Life of Pi

by Yann Martel

Life of Piís narrative revolves around Piscine Patel Ė known throughout as Pi Ė and his struggles when he is stranded on the Pacific Ocean. The novel uses the framing device of an author talking to Pi, who is now middle-aged, about his childhood experiences. The first section of the novel is dedicated to Piís childhood in India, detailing his attempts to find meaning, largely seen through his exploration of religion. There are a number of recurring characters in this section, however, they are rarely characterised extensively but rather exist in order to further Piís narrative in this coming-of-age story.

The bulk of the novel is set on a lifeboat, depicting Piís attempts to survive the shipwreck that kills his family, and the boatís other passengers. Despite initial misgivings, he decides to help Richard Parker Ė the Bengal tiger that has made its way to the boat Ė survive, fearful of being completely alone at sea. Despite its restricted setting, Martelís book is filled with narrative incident, as Pi struggles to survive and assert dominance over Richard Parker. The narrative is fantastical in premise, but Martel keeps it largely grounded through his detail-heavy prose.

Aside from a fictitious authorís note establishing the framing device, Life of Pi opens with Piís lengthy description of sloths, the subject of his zoology thesis. His rigorous description, conveying both curiosity and intelligence, sets the tone of Piís style of narration, which consistently dwells at length on factual details even as it considers the limits of human knowledge. The first section of the novel considers religion and faith, with Pi coming to the conclusion that ďatheists are my brothers and sisters of a different faith, and every word they speak speaks of faith. Like me, they go as far as the legs of reason will carry them Ė and then they jump.Ē Martelís dissection of different faiths occasionally seems trite, but it is refreshing to see a novel that embraces rational and spiritual thinking in equal amounts.

From a narrative perspective, Piís journey with Richard Parker is both impressive and disappointing. The months they spend at sea are detailed compellingly, especially for a concept that sounds so inherently limited, but the novel loses a lot of its warmth and humour as its depiction of a young man growing up is overtaken by the survival narrative. Until the shipwreck, the novel is structured as a series of interlocking anecdotes that make up Piís narrative when combined. The humour is often dry or understated, as when Pi tells the story of Richard Parkerís name, but it adds much-needed texture to the early sections of the novel.

Life of Pi eventually reveals itself not only as a consideration of religion and faith, but also imagination and creativity. It connects these concepts in a way that makes the reader consider their interaction with the novel, and entertainment generally. In this way, it exists not just as a fully satisfying narrative in its own right, but also as a philosophical discussion about why we need art in our lives.