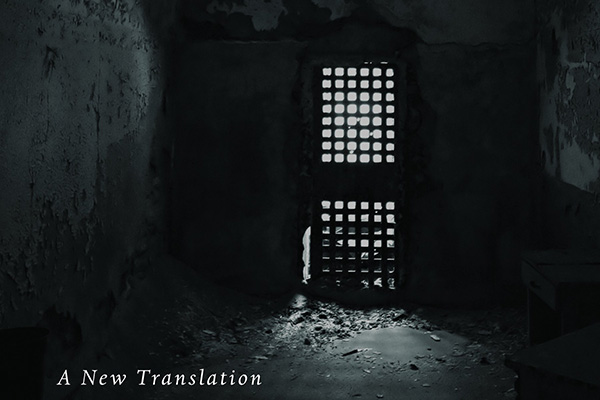

The House of the Dead

by Fyodor Dostoyevsky

Dostoyevsky’s fictionalised self, Aleksandr Petrovich, has been deportated to Siberia and sentenced to ten years’ hard labour. Life in prison is particularly hard for Aleksandr; he is a “gentleman” and therefore suffers the malice of the other prisoners, nearly all of whom belong to the peasantry. As the narrator, Aleksandr is a largely passive observer in the prison, but describes his torment in peculiar detail: the cockroaches boiled in the soup, the baffling and pitiful vanity of the prisoners, and the “terrible and agonising” lack of privacy. Aleksander enjoys not one single moment alone in the ten years he spends at the prison.

The novel doesn’t have a strong plot or focus on building characters. Instead, it is organised around a central theme: the brutality of prison life, perpetrated not only by prison guards and administrators but by the captive population itself. He recalls the guards’ relish in administering unspeakably cruel punishments – often the crimes the convicts themsleves committed. The barracks are deathly cold in winter, unbearably hot in summer, and always stink of shit. Personal possessions and money are coveted and fiercely protected, but never stay with the same man for long – the owner will invariably be beaten unconscious and robbed. Some of the prisoners are kind, sensitive men, others ruthless murderers. Their ingenuity is amazing; they manage to source cigarettes, alcohol, chocolate and even prostitutes whilst labouring outside the camp.

Of particular concern to Dostoyevsky is the blanket use of particular punishments to suit a wide variety of crimes. Religious martyrs, political deviants, the insane, those who killed in defence of others, innocent victims of circumstance and savage murderers are all treated identically. Dostoyevsky is preoccupied with this injustice, as well as the fact that the punishment itself is not suffered equally by the prisoners. Some are half-mad with remorse and guilt for the crimes they have committed; others brag proudly of the strangers they have murdered in cold blood without provocation.

The prisoners are fed adequately; this is cause enough for some of the inmates to have committed murder, simply to escape starvation as “free” people in the outside world.

It was Dostoyevsky’s freedom to doubt that led to his own imprisonment. The portrayal of the prison, with its absurd practices and savage corporal punishments, is a graphic illustration of why the members of the Petrashevsky Circle were so opposed to the Tsarist autocracy and the Russian serfdom.