A Micronaut in the Wide World

The Imaginative Life and Times of Graham Percy

Exhibitions featuring an illustrator are few and far between. Depending on the number of bedtime stories you demanded as a kid, they can plunge you nostalgically back into childhood.

Although he lived most of his adult life in London, Graham Percy was one of New Zealand’s most well-known and distinctive illustrators, having provided visual material for more than 100 children’s books. However, A Micronaut in the Wide World – currently showing at the Hocken Library – demonstrates that his ideas extend far beyond the realm of storybooks.

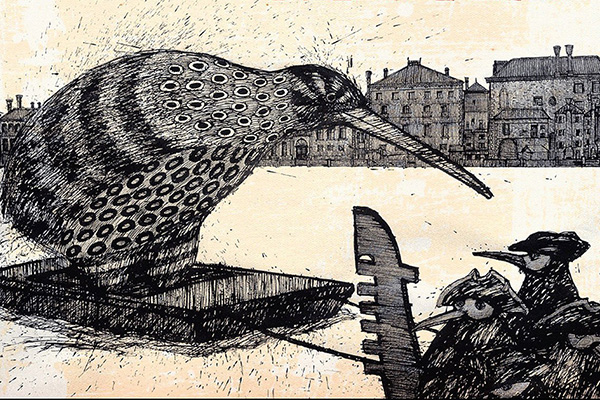

Graham Percy was unknown to me upon entering the exhibition, but his illustrations were oddly familiar. They reminded me of Maurice Sendak: realistic enough to recognise what was being depicted yet with enough of a twist to be disconcerting. The human figures are out of proportion, their heads too large and their figures squashed in a way that makes you want to adjust them / push them into the correct mould. Percy’s style is highly memorable: his plump figures sit in beautifully detailed environments, often with scrawling text hanging in a top corner. Carefully constructed and quirky, they verge on graphic design.

Bordering the two fields of art and design, illustration involves very specific representations of subject matter – much more so than the significant majority of recent “high art.” This level of focus allows illustrations to fit in with a body of text.

Illustration has often been considered one of visual art’s “lesser” forms, but this attitude seems to be changing. In many of Percy’s drawings you notice a distinct awareness of artistic movements such as Bauhaus, possibly a result of his training at Elam School of Fine Arts. In 1994 he published a book called Arthouse, in which he designed each room of a house in the style of an artist he was influenced. (Joseph Cornell was lucky enough to be represented by the bathroom.)

This exhibition gives viewers an overwhelming sense of Percy’s artistic and creative capability, and an insight into his ironic sense of humour. There are endless pictures of famous composers placed out of context, mostly in typical New Zealand landscapes. Franz Schubert emerges from a stream with a trout having found the inspiration for his “Trout Quintet,” and Beatrix Potter, her head an inflated balloon, is depicted casually observing some rabbits above the caption: “Beatrix Potter in her own special balloon watches rabbits dressed for occasion …”

Interestingly, the most captivating part of the entire exhibition is not the works themselves but a 10-minute video of Percy’s house in London, created by the illustrator’s son after his death. Everything is immaculately laid out, each room bursting with art works and collections of objects. One object that stands out as a representation of Percy’s personality is his printer, on which painted black and white squiggles accompany the words “un homage à Wassily Kandinsky.”

Percy died after catching pneumonia on a trip to get art supplies. He was creating and observing the world around him right until his death. With any large exhibition it becomes difficult to maintain the focus needed to really “look” at each drawing, but A Micronaut in the Wide World offers many gems that may touch your heart and possibly make you snort a little with laughter.