A planet named after the Roman god of time, renewal and liberation seems a fitting final resting place for our lovely friend Cassini-Huygens, whose life was spent furthering astronomical knowledge and the liberation of truth from a far-flung part of our small star system in this abyssal ocean of space.

Cassini departed her earthly cradle in 1997, for she was better than all of us.

She was the first brave space probe to enter Saturn’s orbit, and, on September 15th, t’was here that she drew her final robot breath. Passing by Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, Cassini’s trajectory was altered by Titan’s gravity, causing her to head for Saturn’s atmosphere, where she burned up on entry.

Cassini had run out of fuel, and the team at NASA charged with her mission felt that it would be best to destroy her in a controlled way to avoid risking any contamination collisions with the moons Titan or Enceladus, both of which show promise of harbouring life. “Because of planetary protection and our desire to go back to Enceladus, go back to Titan, go back to the Saturn system, we must protect those bodies for future exploration,” stated Jim Green, director of NASA’s planetary science division.

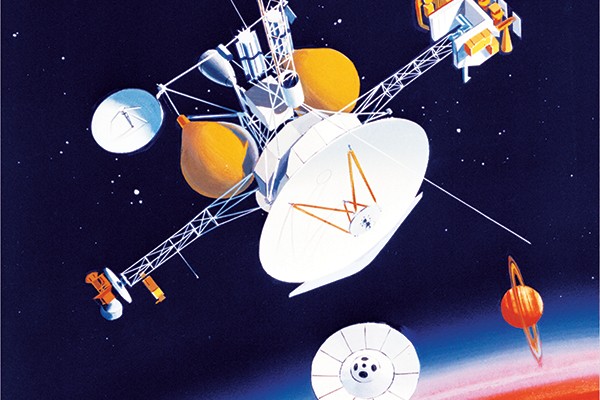

Cassini-Huygens, born in 1982, was the lovechild of the European Space Agency, the Italian Space Agency, and NASA. A combination of NASA’s Cassini probe and ESA’s Huygens lander, she weighed about 2500 kilograms, and measured about two metres tall by four metres wide.

Powered by 33 kilograms of radioactive plutonium-238, she wasn’t always the most popular girl at school. In the late ‘90s, environmentalist groups were unhappy about Cassini’s fuel source, but the cost to run her on radioactive plutonium was more than worth the potential insight she could transmit to us from foreign worlds. Plutonium-238’s decay heat converts to electric energy that would power all of Cassini’s needs, such as her cosmic dust analyzer, magnetometer, radio and plasma equipment, radar, and onboard spectrometers - not to mention all of the imaging systems which have allowed her to send us Saturn’s secrets in such incredible detail.

After her 1997 launch from Earth, Cassini travelled almost 8 billion kilometres, collecting over 635GB of data and snapping almost half a million images. Her first foray was two fly-by stalks of Venus, slingshotting back past Earth and then circling Jupiter. After seven years, she arrived in the realm of the gas giant Saturn - 1.2 billion kilometres from Earth.

Orbiting Saturn 294 times, Cassini completed 162 close fly-bys of Saturn’s largest moon Titan, and pinged photos and data back to us, revealing cold mysterious worlds vastly unlike our own lush temperate home.

Cassini represents an incredible achievement for humans. Years of intelligence, engineering, vision, skill, and a determination to grow and learn as a species. We have shared the lifetime of a plucky little space probe that is currently 1.2 billion kilometres away from us; a place where we may never tread in this harsh, eternally indifferent cosmos. Cassini showed us, in more intimate detail than we could ever have dreamed, what it means to inhabit a universe which is oblivious to us on our tiny little tropical rock.

May Cassini’s short life be a beacon of truth and knowledge for all.