The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

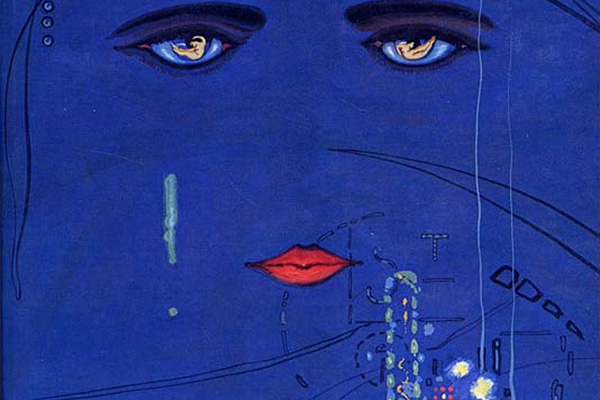

Our narrator, Nick, arrives at West Egg in the hopes of cashing in on the East Coast’s easy money. His new neighbour hosts extravagant parties, and Nick watches as glittering figures dance through the blue gardens until one night he is invited to join them. His host, Gatsby, makes no dramatic entrance; it is as though he wishes to be a guest at his own party. He floats like a ghost through his own house, and has a timeless smile and handsome, all-seeing eyes.

Gatsby has always loved Nick’s cousin Daisy, a beautiful, delicate creature with a voice that sounds like a song. Years later, he buys his house knowing she lives just across the water. Yet Daisy has a husband, Tom, and a daughter. Daisy cries when her girl is born, and says “I hope she’ll be a fool – that’s the best thing a girl can be in this world, a beautiful little fool.” Her husband Tom is a white supremacist, and is having an affair with Myrtle, who is also married.

Everyone cheats on each other, and makes little attempt to hide it. Women fall into men’s arms at Gatsby’s parties, and are referred to as attention seeking “girls.” No one seems to know what they’re doing, so they draw attention to themselves with material things. Gatsby’s car is the centrepiece of his affluence, and yet it is the power of this car that sparks the tumultuous events at the end of the novel.

What’s striking is how young everyone is; it is as though they have been prematurely thrown into adulthood. They foolishly throw their fortunes at elaborate cars, clothes and parties, in a desperate attempt to stave off boredom. By her early twenties, Daisy believes she has “been everywhere and seen everything and done everything.” Perhaps what readers still relate to is the sense of escape that such frivolity brings; throwing parties and getting drunk shows that you’re living life, when really you’re unhappy.

The real tragedy, however, goes beyond the facade of having a good time, and beyond the harrowing loneliness that sets in as the last guest leaves. The saddest thing of all is that Gatsby’s show fails. He only wishes to impress Daisy, yet he fails even to bring a smile to her face. She doesn’t see what he wants her to see, and it’s tragic, frustrating and embarrassing. The moment Daisy so much as hints that she is not fully impressed by Gatsby’s mansion, it’s as though the walls are made of paper. The fact that it is all for show becomes clear as daylight, and there is no justification, no covering it up. His life is a lie, but we already knew that. What’s tragic is that the lie is pointless.

Despite being the most talked-about man in West Egg, no one really knows who Jay Gatsby is. He is built on rumours and the opinions of others, and his personality is extrapolated from his material possessions. As Daisy says: if you hear enough people say something, it must be true. Gatsby is only what other people think of him, and perhaps the message is that, really, we all are.