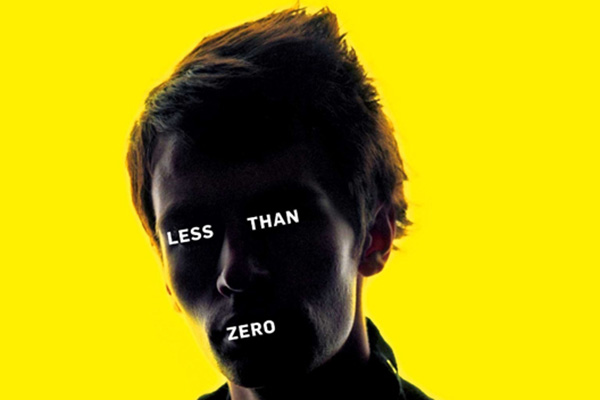

Less Than Zero

by Bret Easton Ellis

While back home Clay avoids confronting his girlfriend Blair about their relationship, indulges in illicit drugs, crawls from luxurious suburban party to downtown club, and enjoys a myriad of sexual relations. It is apparent from the outset that Clay feels as though he is on a different wavelength from those around him; he seems unable or unwilling to engage himself emotionally. Clay is a passive and nihilistic, an accepting observer following a “why not” mantra.

In writing Less Than Zero, Easton Ellis used Joan Didion’s Play It As It Lays as a template, taking her mélange of disparate nihilism, 1960s excess, and clean-cut minimalism, and exporting it into a 1980s diaspora. The novel starts out a little clumsily, seemingly while Easton Ellis finds his stylistic feet, but quickly draws the reader in. I found Clay’s stark narration incredibly engaging, and felt that as a reader I put aside my own ethical and moral standards in order to take part in some serious voyeurism.

It was hard to set down the book the first time I read it, and was hardly any easier the second time around. For the wealthy young characters the sky is the limit, and it is almost impossible not to follow their exploits with a degree of fascination. However, that is not to say that there are no moments in the book that have a real emotional impact. The blunt force of the narration and the utter inability of Clay and the others to demonstrate any more than a fleeting interest in anything outside of themselves was frankly traumatic.

For me, the most upsetting parts of the book were those involving Clay’s childhood friend Julian. Julian seems to have completely lost control of his life; he is in desperate trouble but is unable to get help from anyone he knows. While Julian’s story is viscerally painful for the reader, for Clay it is merely a form of distraction, a kind of stimulation that he cannot get from his own life or from his other friends. While Julian may only be a plot device used to emphasise the enormity of Clay’s disconnect, I felt that he brought a sense of clarity to the morally bereft behaviour of Clay and the other characters; I desperately wanted for Clay to help Julian, and his seeming inability to do so was jarring.

Upon finishing this book I was left with the absolute certainty that my insides had been irrevocably rearranged. It is perfectly constructed and its melancholic acceptance is beautifully relevant to any post-baby-boomer coming to the realisation that there may be endless opportunity in youth but no definable or desirable future left to obtain.