Blackfish

Director: Gabriela Cowperthwaite

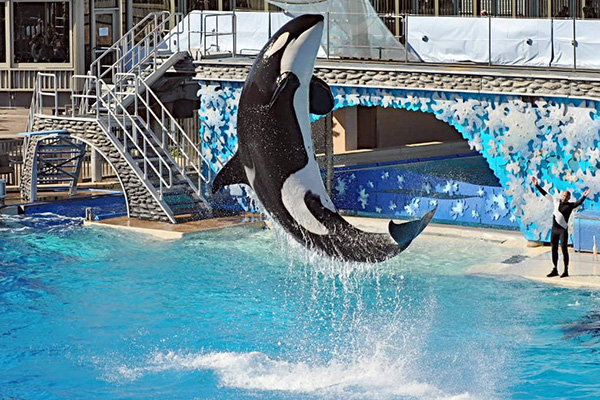

The American summer draws to an end, and no doubt millions of Americans have now attended “Shamu Stadium,” SeaWorld, to see Orca whales wave their dorsal fins limply, jump through hoops and engage in bizarre aquatic acrobats with their perpetually smiling trainers. However, what those spectators would not have been aware of is the amount of complete bullshit they have been feed by SeaWorld to ensure that they go home happy, with a stuffed Shamu doll in tow. The biggest of these lies is that the whales are happy, when in reality SeaWorld’s chronic mismanagement has lead to multiple deaths of trainers and whales alike.

In Blackfish, our “protagonist” is Tilikum, a young killer whale kidnapped in Icelandic waters and sold to SeaWorld. There, the threatment he recieves at the hands of his human “masters” leads him to fall into a downward spiral that Cowperthwaite argues could be a form of psychosis. Blackfish focuses on how keeping majestic beasts such as Tilikum in captivity is a sign of our cultural hubris. We reduce these animals to court jesters or, in SeaWorld’s case, profit-making slaves. Cowperthwaite is unapologetic in her takedown on of the system that has lead to Tillikum’s Titus Andronicus-like fall into psychosis, documenting over 30 years of abuses of power, sub-circus level living conditions and unreported attacks on trainers.

This character study of the whales takes place through interviews with past trainers and “those that knew him best,” which at times makes the film feel like a Crime and Investigation channel special. Every trainer, whale hunter and past SeaWorld employee mentions that they saw the abuses of power that occurred and the slow descent of Tilikum into these dangerous and wild mental states. The moment when an ex-whale-napper breaks down as he recounts how he had to cut open a whale, fill its stomach with rocks and tie an anchor to its tale to avoid a “PR scandal” is particularly disturbing. These interviews are interspersed with amateur footage of whales attacking both humans and one another (something that has never been reported to have occurred in the wild) in front of hundreds of crying families.

The central tenement of this mistreatment, the film argues, is that best practice often does not follow objective reality but rather the vested interest of big businesses such as SeaWorld. While the documentary’s anti-SeaWorld bias is unashamedly on display, it is worrying that SeaWorld “repeatedly declined” to be interviewed. The film may be slanted, but it certainly backs up its accusations with historical and scientific evidence that charges SeaWorld with relying on animal abuse to make a profit, putting their employees’ lives at risk, perjury and endorsing the hunting of endangered species.

The documentary’s title is a reference to the name given to these animals by the Native Americans due to the majestic authority they assert in the wild. This is ironically contrasted with the way in which they are kept in claustrophobic water filled-sheds, released to a slightly smaller pond for a few hours a day to jump for SeaWorld’s many oblivious guests. Indeed, one of the film’s closing shots reveals that Tilikum is still performing to this day, leaving us to ponder whether this creature will feel the urge to “kill again.”

The strength of Cowperthwaite’s film is not in making you feel for the humans who have lost their lives to the orcas, but in making you feel for the whales themselves. Tilikum comes across not as a dangerous animal but as an innocent party who has been abused, demeaned and isolated, making his actions completely understandable. As one of the many marine biologists in the film recounts: “try spending most of your life in a bathtub; see if it doesn’t make you a little psychotic.”

Following on from previous festival documentaries Project Nim and Grizzly Man, Blackfish is a damning tale about how we cannot “tame” animals, given our current understanding of how these social and (undeniably) intuitive animals function. It leaves one with the feeling that watching a show at SeaWorld is tantamount to paying to watch torture.