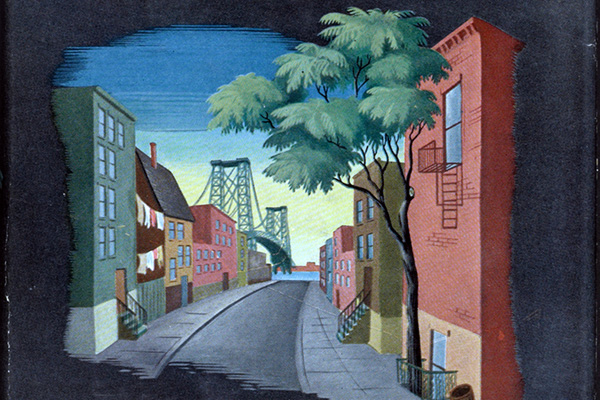

A Tree Grows in Brooklyn

by Betty Smith

It is the turn of the twentieth century, and Francie Nolan seems to understand more about the world than the adults around her. She offers a child’s delightful perception of life. The symbol of the tree seems to represent someone growing until they can look down over where they have been, rather than a person being kept in one place by their roots.

At the age of 11, Francie’s life mostly consists of scrounging the streets for scraps. Her mother Katie is almost a child herself, and constantly has to worry about their next payment, and whether they will have enough to eat. Francie’s creative and handsome father, Johnny, suffers from alcoholism, yet Francie hopelessly idolises him. Johnny represents the bleak decline of the American dream. He still believes in the New Country that has tragically failed him. Katie sees her children encounter the same troubles she did, as generations overlap one another in an endless cycle that traps children in a predictable life.

At 13, Francie decides that she doesn’t like women. When local girl Joanna falls pregnant before marriage, something they refer to as “getting into trouble,” the women throw stones at her. Katie tells her daughter that she must learn from this, and Francie is confused. She decides that because she is told this so often, her adulthood will consist primarily of tracking down grown-ups and thanking them.

Francie’s creativity is squandered. Her underprivileged life leaves little room for self-development. Despite this, she keeps up her writing. Yet Mama never has time to read her work, and Francie burns her stories when her teacher tells her not write about such sordid things as poverty.

Despite their poverty, Katie ensures there are always small pleasures, such as hot coffee, in the house. Francie doesn’t drink her cup, yet it is not wasted. Katie allows her to pour it down the sink to experience, even just momentarily, the carefree joys of the wealthy. It is the biggest shame to feel sorry for oneself. Starving children will turn up their noses at free food, and young Francie gets her first taste of shame over the doll she accepts as a charitable gift to a “poor girl.”

Gradually, Francie’s world begins to widen. She has grown up in a small community, hearing whispers of exciting places such as New York City, but when she gets a job in the city she is miserably disappointed. Even the dull experience of the famous train ride shatters her dreams – “like Alexander the Great, Francie grieved, being convinced that there were no new worlds to conquer.” She is only 14 years old. The children of Brooklyn, it seems, are worn down into a premature adulthood.

In this book, there is much emphasis on education as the key to breaking the cycle of poverty. However, particularly with the late arrival of her third child, Katie gives up on the idea of her children having a better life. The Catholics in Brooklyn have more children than they can support, and to her utter despair, Francie must work rather than attend high school. Growing older, Francie loses faith in God. She tells her brother she doesn’t believe anymore, because she never sees proof of his work. Finally, war provides the final blow. Prices soar and jobs are scarce. Francie finds herself at a crossroads, close to repeating the cycle of her own family, and making the same decisions her mother made when she was 16.

The book highlights the failure of adults to provide for their children. Francie’s parents have the best of intentions, yet are unable to give Francie the life she wants. In Brooklyn, children are a nuisance, and are treated by adults as “loveable but necessary evils.” Yet Francie Nolan is an exception. She seems to grow. And maybe in time, her children will have a better chance at life than she did.