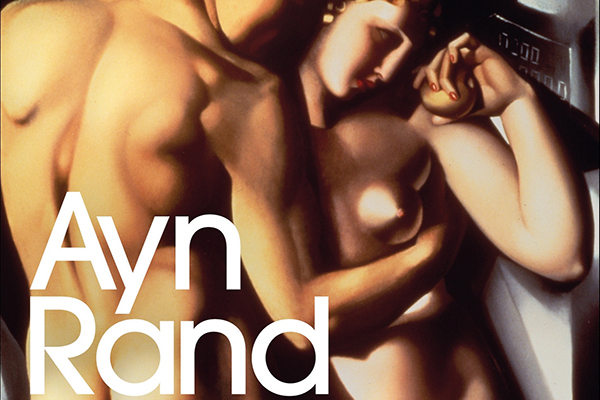

We the Living

By Ayn Rand

Many Russian authors have a tortured relationship with their motherland, but for Russo-American author Ayn Rand, Soviet Russia was an object of hatred. This, her first novel, was written after she had escaped to America, the promised “abroad” — a word whispered in reverent tones throughout the book.

The scene is 1920s post-revolutionary Russia, and the family of Kira Aragounova are returning to the city of Petrograd (St Petersburg) following the final defeat of the White army by the communist Reds. Kira’s father was a wealthy industrialist prior to 1917, making their family class enemies of the new Soviet state. The story follows their struggle to avoid starvation in the day-to-day depravations and insanities of the new communism. But this is only the backdrop to the real story Rand wants to tell.

Rand was not keen to write her first novel about the Soviet state. Having only just escaped Russia, and still painfully young for a novelist, she felt unprepared to write about “adults”. However, she became convinced that it was necessary to deal with her Russian past in order to move on from it and into her new life in America.

Rand begins with a standard plot: a young and virtuous girl who must enslave herself to the whims of a villain in order to save her heroic lover. But from simple beginnings she entwines within this love triangle an unforeseen twist used to highlight the evil of destroying individuality and free will. You can almost feel the young Rand (25 at the time) developing her ideas about Russia, communism, philosophy, and love as she works her way through the extensive chunks of dialogue throughout the book.

We are asked to believe that if free, Kira’s lover Leo Kovalensky would be a heroic and virtuous man. And that his failings, in the end his total failure, are not his fault, but the result of throwing a man’s will up against the authoritarian control of the Soviets. To me, Leo seemed weak compared to the nobility to anti-hero Andrei Taganov, who maintains his values throughout, despite his pursuit of an ignoble goal, and maintains his honesty when he realises the folly of his endeavour. Yet as you read, you can feel that readers would relate to each man in different ways, seeing parts of themselves in each and feeling for whichever one they identify with.

The fascination of reading Rand’s earliest work is tied into her later life. She is the founder of the philosophy of objectivism, which places the happiness and success of the individual as the ultimate goal of each person’s life. In a godless world, individuals must ensure for themselves that they achieve that which is “of their highest reverence”. Any system of governance that attempts to take that away, to tie the individual to the greatness of the commune, creates the greatest form of injustice.

Rand develops this new philosophy throughout the book in the tragic conversations between the protagonists about what they stand to lose to the tyranny of the communists: how inherent evil has the power to destroy them or drive them to destroy themselves. And while each of the three protagonists travels a different path, none survives whole.

Rand’s tempo and pacing are at times infuriating. She spends pages describing the billowing smoke of the primus (admittedly her chosen symbol of the depredations of the age), while racing through moments of fraught tension and obvious significance that could be more fully developed. It reads like the work of young author with much to say but a sense that time enough to say it all may be running out.

Read this book if you are interested in love, history, politics or philosophy. Its ideas are not hidden, and of all Russians authors, Rand is the easiest to read. It is the kind of book that allows you to choose your own hero, and then seeks to destroy them.