Memories Of My Melancholy Whores

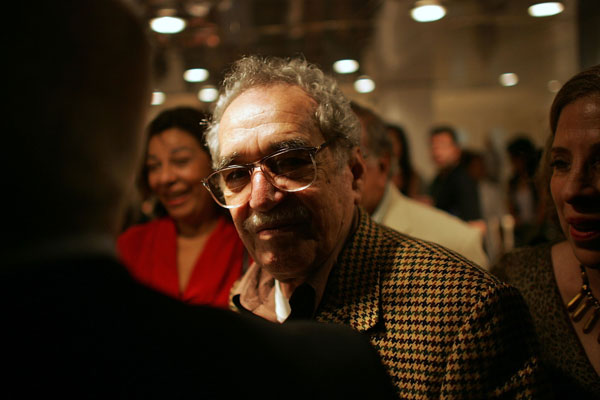

by Gabriel García Márquez

The narrator’s external image of a gentlemanly bachelor who stays at home with his books and classical music hides a chauvinistic mind, in which he sees all males – including his cat – as potential threats, and all females – including his mother – as potential sex. He has no real friends, and has never slept with a woman he has not paid for. When the narrator starts to meet the girl when she is awake, he decides he prefers her sleeping. He doesn’t want to know her name or see her dressed, or anything else which would make her more than a blank slate for him to create his fantasy on.

This detachment from the girl’s human-ness is a disturbing insight inside the mind of a man unable to distinguish a person outside of his own qualifications. This is particularly unnerving when observing the narrator’s attitude to animals and small children: “They seem mute in their souls. I don’t hate them, but I can’t tolerate them because I’ve never learned to deal with them.” So perhaps his way of learning to “deal” with an intimate relationship is to “fabricate” a person over whom he has complete control over, and can therefore “tolerate.” The narrator finds the girl “less real” in the flesh than in his memory; when he finds out her birthday he is troubled that she is “real enough to have birthdays,” and at one point he traces the lines on her hands while she sleeps to take to a fortune teller, so that he can “know her soul.”

Illusion in love is a major theme; from the love of a prostitute, to the love letters from people reading the old man’s newspaper column, and the narrator’s preoccupation with his beautiful, consumptive mother who died when he was 14, about whom secrets are revealed which upset his saintly image of her. There is some twisted symmetry in his imagining the girl charging around his parents’ old home helping him repair the leaky roof and cooking for him, and his gifting to the girl some of his mother’s old possessions, including jewellery and clothing.

The obvious comparison to Nabokov’s Lolita reveals little of protagonist Humert Humbert’s self-loathing and paranoia. But, perhaps the absurdity of a 90-year-old man finding excitement in his life via a teenagerly delusion of manic, unrequited love replaces the former as an excuse for the book’s deplorable content. The story is totally creepy but weirdly mesmerising, with the focus not so much on melancholy whores as on a sad old pervert. I found the relationship between the geriatric near the end of his life and the near-paralytic girl to be almost necrophilic; at one time the old man even checks her pulse to make sure she is still alive.

The plight of the girl is not an issue dealt with in the book, despite mentioning her malnourishment. There is no great revelation or moral awakening, which suits its amoral theme. It is impossible to read a book of this subject without considerable protest from your most basic morals, but both author and narrator are entirely unapologetic of this, telling the story in simple, honest prose which is neither self-deprecating nor grandiose, allowing the reader to enjoy a fascinating story without feeling that they, the author or the narrator need to justify themselves.

Lucy Hunter