Wandering Womb noun

a) Spontaneous migration of the uterus within the female body, anywhere from the pelvis to the mind.

Characterised by symptoms including but not limited to: Headaches, tremors, fainting, chest pains, abdomen pain, vertigo, sexual desires, intellectual thoughts, homosexuality, tendencies to cause trouble, being old, feelings of sadness, happiness or any kind of thought or feeling.

Treatments include but are not limited to: rest, perfuming your vagina, marriage to a wealthy man, childbirth, exorcism, lobotomy or death.

The description for the ‘wandering womb’ may read like a work of fiction, but for centuries it was a common diagnosis for women presenting with virtually any physical or mental ailment. The first description of the condition dates back to 1900 BC when ancient Egyptian physicians claimed that “spontaneous uterus movement within the female body” was the cause of depressive symptoms in women. It was in Ancient Greece, however, that the term hysteria was first recorded – hystera being the Greek word for uterus. In the 5th century BC, Hippocrates detailed a “feminine madness” that resulted not from an overtly oppressive society, but from “a uterus in distress”. It stuck, and for 4000 years it remained a catch-all wastebasket diagnosis. Almost any pain suffered by a woman could only be her animal-like uterus scurrying around causing a ruckus to her innards like the rat in your flat’s walls. Nevermind that the uterus is internally fixed in place by multiple ligaments, and connects to the vagina via the cervix.

You may ask: what could have caused a uterus to become so distressed? Perhaps it was the pain of having no political rights? Or the weight of a world that forbade you a career beyond childbearing? Of course not. Don’t be daft. Ancient physicians believed the cause was a “deviation from a woman’s intended function” – that is, the uterus grows sad when it’s denied reproductive sex with a man. The female body was imagined to be “cold and wet” and “vulnerable to putrefaction”, while intercourse promoted bodily cleansing. Ah yes, the cleansing act of unprotected sex in the days before STI treatment. In what could be the words of a 14-year-old boy in Year 9 science, the great Hippocrates theorised “vagina equals yucky, penis equals awesome”. Patients were prescribed a dose of dull marriage and regular sex (also probably dull).

Physicians claimed that the condition was rife among “virgins, widows, and spinsters” – better known today as the girls, gays, and theys. Even more bizarrely, a wandering womb was believed to be easily enticed by fragrances. Women were instructed to sniff ammonia salts to drive it lower in the body or perfume themselves with floral scents (that can’t be good for your pH) to lure it back into place. Worse yet, as the world entered the Middle Ages, the popularity of witch hunts crept into medical practice. Now you could be hanged or burned at the stake for not wanting to have sex with men, or in milder cases endure a cheeky exorcism or two.

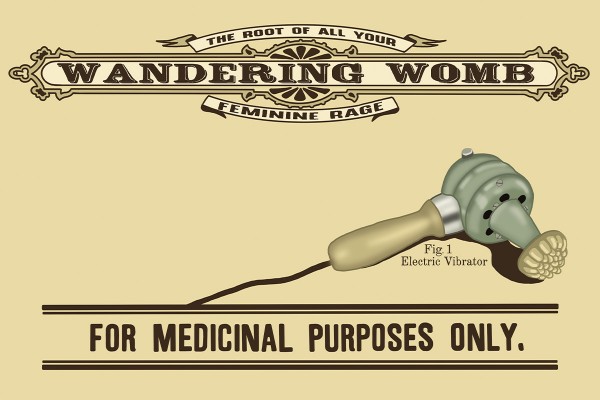

Unsurprisingly, the range of potential hysteria symptoms was so broad that it was responsible for the misdiagnosis of hundreds of other actual disorders. Women with anxiety, depression, PTSD, epilepsy, and bipolar disorder were all lumped together as hysterics. In the few cases where abdomen pain and sexual desire were the main symptoms (and long before the invention of the Satisfyer Pro 2), it’s possible that these patients were genuinely suffering from sexual frustration. However, that’s certainly not synonymous with a desire for children. Furthermore, you can imagine a prescription of forced marriage and childbirth probably didn’t hit the spot. For much of history, hysteria was likely the result of male physicians failing to understand the happenings of a female body. Shocker.

The hysteria diagnosis changed in the 1800s when every Psychology lecturer’s favourite man Sigmund Freud entered the chat. Astoundingly, he concluded that the idea of a little angry demon uterus was ridiculous and that men, too, could suffer from hysteria. Progressive for the 1800s? Turns out, no. He followed this up by declaring women to be more susceptible because of their “frailty of character” – in those times perhaps just a lack of warmongering. Men remained rarely diagnosed with hysteria. However, symptoms narrowed to those associated with the nervous system.

The founding of psychology resulted in another rise in the commonality of the diagnosis. As the distressed uterus theory fell out of fashion, treatments for hysteria changed. The most common cure was rest; women were to refrain from any strenuous physical or mental activity. To the modern woman, that might mean skipping a Unipol group fitness class or late night study session. But in more severe cases, physicians opted for electric shock therapy or lobotomy – forced severing of the frontal lobe from the rest of the brain. As psychiatry gained popularity in the West, mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia, anxiety and depression, edged out hysteria diagnosis. Eventually, the illness was legislated out of existence in 1957. However, the term lingered until as recently as the 1980s. The trauma, even later still.

Hysteria served to justify the societal belief that women were inferior to men. They were fragile and vulnerable to ailments of body and mind. It’s easy to imagine that much of these women’s distress was a direct result of the pressures faced when living in a deeply misogynistic society. For centuries, hysteria helped to reinforce women’s societal role as purely reproductive. Under the notion that unfulfilled duties to men resulted in bad things happening to women, they were subject to greater pressure to marry young and have children.

Hysteria, while no longer attributed to the ‘wandering womb’, has a legacy that remains today. When you hear the word hysteria, what comes to mind? Is it thousands of screaming 13-year-olds at a Harry Styles concert? Or crowds of shoppers shoving each other in a Black Friday Sale? It’s not a coincidence that many of us picture only women and girls. The word continues to reduce women’s valid thoughts, feelings, and experiences to irrationality.

Worse still, hysteria set the precedent for long-standing inequalities in healthcare. Medical data on female bodies remains woefully scarce compared to our male counterparts. Anatomy textbooks stray away from depicting the diversity of labia shape and size and, despite being homologous organs, diagrams of the clitoris are not as extensive as those of the penis. While endometriosis affects 1 in 10 people with uteruses, patients in the US are likely to wait 10 years after symptoms appear to receive a diagnosis, with similar delays in NZ. That’s a decade of suffering before they’re given answers, with barriers often rooted in misogyny – patients are often led to believe that crippling periods are normal, while physicians are misinformed about treatments. Even further, 70% of those affected by chronic pain are women, yet 80% of pain studies are conducted on male-only participants. The stats are even poorer for uterus-owners who are indigenous, queer or disabled. Studies show that women’s pain is often underestimated when compared to men’s, making women subject to longer ER wait times on average, and less likely to receive painkillers – though more likely to be offered psychotherapy instead. These inequalities are vast and can have life-threatening consequences.

While we no longer believe that the uterus is an animal, angrily scurrying about the women’s organs and wreaking internal havoc, it's clear that the echo of this nightmarish belief still plagues us today. So uterus-owners, the next time you express a genuine feeling and someone dares to call you hysterical, be sure to remind them that your uterus remains in the right place. Then kindly tell them to fuck off.