Critic (still) tackles election year

The aftermath

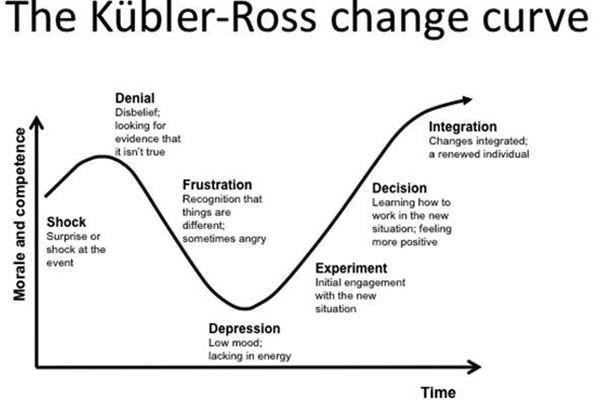

While I never got so far in the denial stage to sign the petition for a recount of the results, it was frustrating to see so many people ignore the lies and what is going to happen to our environment in light of a third National government. Moreover, I just couldn’t see how it happened, when support seemed so strong. The question, for many, was “what went wrong?”

Thus, the post mortems have come thick and fast, a blend of statistical polling booth analysis and emotional reflections; and an abnormally long Labour caucus on Tuesday that left a pack of journalists outside with only Twitter to comfort them.

In reading through the wide variety of interpretations, one thing became abundantly clear: I live in an echo chamber. Beyond the hive of Young Nats, the majority of people I associate with are lefties; much of the political engagement I feed off inevitably comes to the conclusion that if people “understand” or have “empathy,” they’ll vote left. It’s only in the wake of the election that I’ve come to realise how dangerous this is.

To be fair, I still believe that my party is the most empathetic and has the most comprehensive policies, but that’s what being in a party is about – this is not a critique of policy or marketing; this is a critique of myself, and others like me, who see progressive politics as inevitable purely because they’re progressive. Being on the right side of history is a thrilling prospect; it brings with it a relentless idealism that assumes our time will come, that people will realise this and jump on board.

Well, they haven’t jumped; they’ve stayed on the shore.

I took to Twitter to crowd source answers about why the National Party gained a much higher proportion of the Otago vote (37 per cent at the University polling booths, exclusive of the extortionate number of special votes, which haven’t been counted yet) than I anticipated; especially given the plethora of resources that indicated the left is better for students, women, the climate, you name it. Interestingly, this attracted David Farrar, who, unlike a certain member of the Young Nats, hasn’t blocked me on Twitter after my Nicky Hager article.

The discussion generated two distinct factors, both of which I found useful and had suspected previously. First, the simplicity of the National messaging and the streamlined nature of the right-wing campaign in combination with a right-leaning media meant the YNs were easy to absorb for non-political students. If you sit on the right, the imagery is pure and clear: blue. The intensity of the right wing focus on voting for National was all consuming and probably effective.

The second factor is the plethora of voting information that saturated the political sphere for months before the election. There was guide after guide, group after group, all providing reasons why voting for the left is better; but very little of that energy was dedicated to encouraging people to do as such.

In its breadth, this information probably became white noise and off-putting to those who just didn’t care. While the raucous celebration of progressivity got louder and louder for those of us involved, a number of students fell through the cracks and we didn’t notice. One of the YNs responding to my Twitter question noted, “it indicates that student politics is not representative of students, and majority of student voices are passive.” All of the ruthlessly nonpartisan campaigns and analysis groups appealed not to the non-voter, but to each other. Thus, the young and left echo chamber was born.

It also points to a wider issue in the way the left assumes informed voters will vote left. Much of the energy of lefties was spent, this campaign, on education; the assumption being that if the facts are hung out in full view, people will come to the “correct” conclusion. As we’ve seen from this election, this just isn’t the case.

Providing analysis is, of course, an incredibly important activity. Educating students and wider New Zealand should undoubtedly be the focus of some election groups, as no one should ever enter the polling booth uninformed.

Where it becomes problematic is where you add party lines. The conservative youth didn’t campaign on educating students, their message was clear and simple: vote National. To be honest, it has only been the progressive student groups who have focused on educating their peers; thus drawing energy and manpower away from political groups who would’ve undoubtedly benefitted from their help.

George Lakoff, an American professor of cognitive science, has long since criticised the progressives for framing and campaigning poorly. He argues that in order for the left to get back on track, what must happen is “the abandonment of argument by evidence in favour of argument by moral cause; the unswerving and unembarrassed articulation of what those morals are.”

According to Lakoff’s analysis, if the New Zealand left are to draw in the students and the apathetic, we can’t rely on the evidence-based resources that we did this campaign; and rather than pointing to a column on a graph that says Internet-MANA is strongly for students on the assumption that someone will absorb it, there needs to be the ruthlessly on-message intensity of the Young Nats’ campaign, however cultish it can seem from the outside.

Lakoff further notes, “political ground is gained not when you successfully inhabit the middle ground, but when you successfully impose your framing as the 'common-sense' position.” If nothing else, this might help to explain why New Zealand First’s “It’s just common sense” resonated with enough of the population to gain nine per cent of the vote.

In all honesty, it’s a catch-22. The job of educating students politically is one of the most important there is; but if it’s mainly initiated by people who’re members of Labour or the Greens, that leaves said parties with a substantial amount of their youth membership unwilling to express their party lines. If politics is as simple as popularity, it’s necessary that these parties seem popular.

Perhaps, after all our effort, it comes down to this: people don’t want to be told how to make up their minds; they want to be told who to vote for.