“Don’t wait, just go,” is Bernard Hickey’s advice to students who want the security of owning their own home. Bernard is an economist. He is perhaps even more pessimistic about the prospects of home ownership for young generations than the doomers themselves. If you don’t want to be a serf to a landlord class forever, either jump across the ditch or start looking for a partner whose family already has a property portfolio, he reckons.

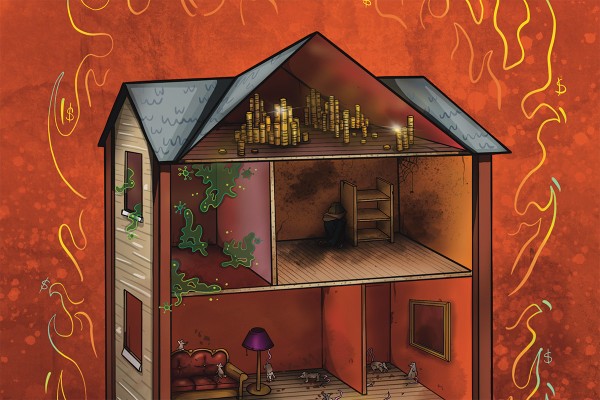

The high price of housing is the end of the egalitarian dream, according to Bernard. “Half of the kids growing up now are growing up in rental accommodation. Half of the nation is being sentenced to live in cold, mouldy, incredibly expensive houses. That means more trips to hospital with chest infections, having mental health problems, not being productive. That's an awful situation. It's not success.”

A housing crash is unlikely to happen because politicians on both sides of the aisle are committed to maintaining house prices. “Most New Zealanders who vote, they think it's a great scheme,” he said. “Why would anything change now? The Prime Minister is in control with a majority in parliament. She told us at the end of last year that she wouldn't do anything that would drive prices down. She said her role was to protect the assets, which is the main home.”

The government switched on the money pump to stop the economy collapsing because of lockdown. We may have avoided another Great Depression, but instead we got petrol poured on an already overheated market. Was it worth it? When I started writing this piece in the first semester, the national median house price had risen 28.7% over the last year. The latest figures from August show a 31.1% increase.

According to a survey by the Building Research Association of New Zealand, almost a third of rentals were deemed by assessors to have been poorly maintained, compared to only 14% of owner-occupied properties. Across every metric, renters are worse off.

As of June, 63.9% of bank lending in NZ is tied up in housing. For comparison, 19.9% and 12.5% of loans went to the business and farming sectors respectively.

New Zealand house prices have risen, in real terms, 259% since 1989. That’s compared to 149% in Australia, and 98% in the United Kingdom. There is no end in sight to this nightmarish rollercoaster, according to Bernard. He sees “another doubling in the next five years” if New Zealand returns to its pre-Covid policies.

Ashley has recently dropped out of her postgraduate course to go into full-time work. She’s confident that her and her partner will achieve their goal of getting on the property ladder within a year. “My mum is a real estate agent,” Ashley says. “So that is a huge help, in terms of: she has all the contacts, she knows the good brokers and the bad brokers, and the good banks and the bad banks.”

Patrick, a recent graduate, got a house that was “partially burned down by a crackhead for the insurance money” at a mortgagee sale with some help from his parents. He was 23. “I want to get out of here as soon as possible,” Patrick says. “It's a freak occurrence, this entire thing is accidental.” He knew that getting a foot on the housing market was now or never, and considers himself lucky to be a homeowner in “bumfuck nowhere”. Patrick lives in Milton. “I’m possibly the last 25-year-old to ever have a house,” he says. “I don't know what's going to happen [with the housing market] in the future. It’s going to get worse. It’s going to get worse and worse.”

Fourth year student Emily says, “I am very jealous of the previous generations’ housing security. Renting can really take it out of you. You have to compromise with a household of adults with varying needs and desires. A house you can mostly do as you please.” She says her “only realistic hope of home ownership is a tiny house” which she says would involve “effectively having to shit in a bucket.” Her parents have “almost paid off” their mortgage, “but won’t have the income, being teachers, to help me.”

Housing advocate and architect Jade Kake reckons that “we almost need a managed crash, which people don't want to hear because their savings are tied up in property.” She reckons “we need some pretty serious government intervention,” but is optimistic about the likelihood of Labour effecting real change. “I'd rather be advocating to a government that is doing broadly well, and really just focusing on how to improve what they're doing, rather than when they're way off track,” she said. “I think this government's tackled some things that you would think would be quite politically unpalatable, but still somehow got them across the line.”

According to Bernard, it will take 100 years to return to affordability following the government's current policy settings.

Wealth inequality researcher Max Rashbrooke is more optimistic. He says the best case scenario for a return to affordability is 15 to 20 years if a year-on-year decrease of around 5% could be managed. “I wouldn’t look to engineer [a crash]. Any government that allowed that would be immediately voted out.” He concedes that for young people starting a degree or graduating it’s a raw deal, but emphasises that “there is nothing inevitable” about the current state of New Zealand’s housing hell. A 30% fall would only wipe out the last year of capital gains.

“They have been saying a crash is around the corner for years,” says Emily. “A clean slate would be good. The state of New Zealand housing is disgusting anyway, both in regards to quality and ownership standards. How can one family own over 160 flats in Dunedin alone?” But she reckons “a crash wouldn't change much unless it came with substantial and progressive housing policies, such as raising insulation standards to match the UK’s.”

Ashley says, “I'd be lying to say that once I was a homeowner, I would want the property market to crash the way that I would want it to crash now.” She believes that while “everybody needs access to affordable housing” and “you should probably be capped at how many homes you're going to own, and therefore how much you can make from rentals and shit like that,” she can “100%” see herself becoming a landlord in the future.

“Just because I disagree with it, doesn't mean that I won't use it to my advantage if I get there. I want to be able to provide for my kids. And if that means I have to own three homes so that I can send them to uni without them incurring $50,000 of debt, well, so be it. I will do that,” she said.

“I don't think there should be private landlords,” Jade says. The point of homeownership shouldn’t be to make massive capital gains, but should rather serve as a base for a broader social wellbeing, she says. “If you're benefiting from a deeply unequal system, somebody else is losing out.”

“I do think it's incumbent upon us to really think about the consequences of our actions and understand the structural factors, rather than just thinking ‘I'm going to make my own life better,’” Jade said. The problem with moving to Australia is that it moves the problem around, to a different set of appropriated indigenous lands with a discriminatory immigration policy.

For Jade, a paradigm shift is needed in the way Kiwis look at housing. “The important thing is that we start encouraging, incentivising, and actively pursuing collective ownership. I'm not really too fussy about the scale, I think we could accommodate a range. We need to move away from individual ownership, I think that's the only way we're going to stop treating housing as a commodity.”

She points out that collective ownership and living is good for wellbeing, an aspect of housing hell underlined by Patrick, who finds living in the sticks, as well as home ownership, isolating. “I'm painfully self-aware, to the point of probably beating myself up on a daily basis, about how privileged I am. And I don't want to talk to people about that. Because it seems like I'm gloating,” he said.

“I think political activism is really important,” Jade says. “I don't think that trying to get on the ladder is a good idea.” Rather, she advocates that today's youth try to change the ladder so the system works better for everyone. “I've got a bit of optimism, at the speed of change, just from what I've seen in my lifetime.”

“There's less chance I’ll be able to own my own home than a fresher trying to get home from Toga without being egged. I feel as optimistic as a Lime in the Leith,” said Adam, a postgraduate student. “Prices have to come down. Right now they're so expensive we’re not going to be able to afford them full stop. If the government cares about students the prices have to come down, it's as simple as that. There's no room for half measures. That's why the decision to abandon the capital gains tax was so cowardly. We know we need a wealth tax. It's just slamming us down in the gutter and forcing us to rent shitty flats with mould on the windows for the rest of our lives.”

So what is the answer to housing hell? It seems like there are four: you can jump ship or jump aboard (if you’ve got the privilege to burn), you can resign yourself to having a Quinovic-branded jackboot resting on your face forever, or you can join with others to make a change and banish suburbia to the shadow realm, where it belongs.