It was the second or third week of uni. I was still riding the high of being the first in my whānau to attend university. With three scholarships under my belt, a double degree ahead of me, and a fresh start away from Whangārei, everyone said I was going to do great things – and honestly, I wore that like a badge of honour. But once the excitement faded, reality settled in.

The scholarships didn’t stretch far. I didn’t have the same wardrobe or confidence that everyone else seemed to arrive with. I became “the one with the scholarship”, which came with its own pressure: always performing, always proving I deserved to be there. I’d traded one label for another, from ‘the smart one’ to ‘the exception’.

Most of us were in competitive first-year programmes, and I was always conveniently nearby when someone felt like venting about Māori entrance schemes – how my theoretical B- would apparently trump their hypothetical A+, just because I was Māori. We weren’t even in the same programme. One person even told me I didn’t need to attend tutorials because “Maaris just get in anyway.”

I was one of only two Māori girls in my hall, and people constantly confused us. It became a joke – the kind that stops being funny real quick. She was everything I wasn’t: tall, gorgeous, accomplished. I’d walk around with my timetable scribbled on a sticky note, in the only shoes I owned – a pair of $6 jandals (the good kind). Out of shame, I started to overcompensate – overworking, overspending, overdoing. After the shock of my first year, I refused to be caught doing “not enough” again. I’d rather be too much than risk being seen as undeserving.

And as anyone would, I crashed and burned. But no one could ever know. I was the trailblazer – for my whānau, my iwi, my people – and they weren’t about to find out otherwise. Honestly, it broke me.

For many Māori students, university is a chance to grow, leave home, and do what no one else in your whānau has done. But alongside the excitement comes an undercurrent: justifying your presence, pushing back against stereotypes, and navigating a system never built with you in mind.

Like most students, we juggle assignments, part-time jobs, and the loneliness of being far from home. But layered over that is a cultural load – often invisible, always heavy. It’s the expectation to show up for kaupapa, to represent in spaces that weren’t made for us, and to quietly educate those around us – the constant mental gymnastics of making others comfortable with your presence.

There’s always the unspoken demand to be the “good kind” of Māori – or face the smug assumptions of being just “another hori”. All of it builds. Quietly. Relentlessly.

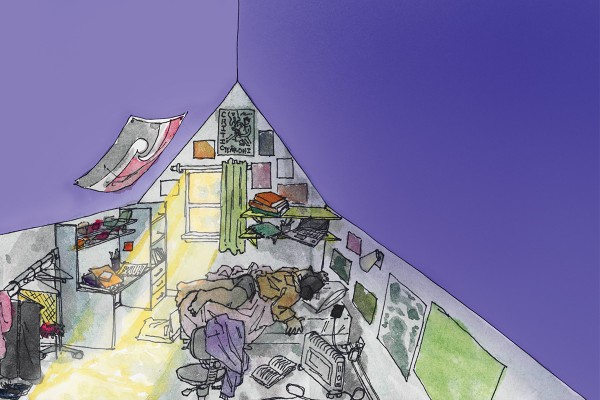

But burnout doesn’t knock. It creeps in. It’s more than just being tired – it’s a full-body shutdown. Your brain starts buffering, and even brushing your teeth feels monumental. When you’ve been raised to be grateful, to never waste the opportunity, rest starts to feel like failure. And that’s when it breaks you. Not all at once, but slowly, under the surface.

It made me wonder: how many Māori students are burning out quietly, because pulling back feels like letting someone down, or getting left behind? Critic Te Ārohi spoke with Te Āwhina Pounamu Waikaramihi, a wahine of many powerful firsts, about the pressure, expectations, and quiet exhaustion that come with always being the one to represent.

If I Don’t Do It, Who Will?

At first glance, Te Āwhina had it all together. The eldest daughter, the first in her whānau to go to university, former Officer on Te Rito (the executive of Te Rōpū Māori) and, in 2022, the first Māori woman to serve as Political Representative on the OUSA Executive. A connector. A leader. The dependable go-to. But behind the smiling face and packed calendar was something less visible: the slow, quiet creep of academic burnout.

Te Āwhina grew up between Kerikeri and Whakatāne as the eldest child of eight in what she calls her “very dysfunctional, crazy, big Māori family”, a role that shaped her into a natural caretaker long before she ever set foot on campus. Now a Master’s student and, perhaps ironically, in Peace and Conflict Studies, her journey reflects the quiet pressures that tauira Māori often carry well before their first assignment is even due.

When talking about her upbringing, she recalls the rocky road of growing up in a split family with parents who don’t get along: “It was full of crazy times.” From a young age, she learned to carry others – emotionally, mentally, and sometimes physically. Despite the turbulence, her parents – academics themselves – were among her biggest inspirations. “They’ve always wanted us to go to university and follow in their footsteps,” she says. Her entrepreneurial father, full of big ideas, sparked her interest in commerce. “He doesn’t necessarily have the funding or resources to back his entrepreneurial mind, but he’s the reason I got into business.” And it was her parents’ deep love for history and te ao Māori that inspired her to pursue Pacific Island Studies.

Te Āwhina describes her first few years in Ōtepoti as “fun and transformative”. “[It was] a real time of discovering who I am and finding my identity or how to express myself in different settings,” she reflects. A fresh start. A change of scenery. The kind of escape that draws many incoming tauira, eager to shed the weight of small-town expectations and step into something new.

Even so, the drive to pursue higher education wasn’t just academic – it was also about escape. “I couldn’t wait to leave home and just get out into the world,” she says. “I applied for a scholarship to come here, and I only applied because there was a Māori woman travelling the motu (country) to inspire other Māori students to come to uni.” Even talking about going to uni seemed to be a big deal, let alone looking into applications and scholarships, and all of the admin that comes with it. In her final year of school, Te Āwhina was awarded a scholarship to attend university, which sealed the decision. Ultimately, she says, it was her whakapapa to Kāi Tahu that brought her down to Ōtepoti. “I’ve always wanted to make that connection,” she says.

But the decision to leave goes beyond chasing opportunity or reconnection – it comes back to carrying expectations, too. “What first comes to mind is breaking cycles in my family,” she says, reflecting on the weight of being the first. “If I don’t make those changes in my family life, or if I don’t succeed academically, who then will do it?” That sense of duty followed her into every lecture, every late night, and every missed family moment.

When things started to unravel partway through her degree, it seemed that there had been no warning sign. “I fell off the wagon halfway through,” she says. “I had to explain to the University why I wasn’t doing so well academically.” Fortunately, she found support in the people who understood her context – kaiāwhina, Māori staff in her department, and the counsellors at Te Huka Mātauraka, the Māori Centre. “I told them straight up: I’m the eldest of my very dysfunctional, crazy, big Māori family, and I carry a lot.” Sometimes, that meant putting whānau ahead of her studies. In one instance, she recalls leaving Dunedin to support her sibling. That decision came at a cost – missed classes, failed papers – but for Te Āwhina, there was no question of doing it differently.

By her second and third years, the toll became undeniable. “We’re the ones checking on others, so we don’t have people checking on us,” she says. The stress showed up physically before it ever showed up on paper. “I lost so much weight because I was so stressed. I wasn’t eating properly.” Few people noticed – or if they did, they didn’t ask. Until one friend did. “He said, ‘Are you okay? You don’t look so well,’ and I just broke down. It was the first time someone actually did something.” Other comments weren’t as kind. “People thought they could comment on my body because I’d lost weight. Someone even said it looked like I was on drugs,” Te Āwhina shares. “Little did they know, I was going through it.”

That year, she failed more papers than she’d care to count. Behind the transcript was something harder to measure: a slow unravelling. And it didn’t happen overnight.

Seen But Not Supported

Burnout doesn’t look like laziness. It comes quietly, and all at once. It’s insomnia, headaches, detachment, and emotional numbness. Crucially, it’s also not something you push through by working harder. Te Āwhina describes her own experience clearly: “I not only feel like I'm always on, I feel like I have to be on. Even when I’m off, my mind is still going.” That compulsion to stay switched on is a symptom of deeper systemic and cultural pressures – what some big thinkers are calling “depleted mauri” where chronic stress and overwhelming demands drain your life force.

Te Āwhina only learned the term “burnout” at university, during a faith-and-wellness workshop. “I thought, wow, I can resonate with that,” she remembers. But recognition didn’t stop it. “I push through, and then I really crash.”

The causes are cumulative: academic rigour, kaupapa overload, cultural expectations, whānau commitments, and parenting. “I’ll sign up for things because I believe I can juggle it all […] then I realise I’ve overestimated my capacity.” And when she does pause, even slightly, it’s accompanied by intense guilt: “I feel a lot of mum guilt. Like if I'm not studying, or if I'm not working, I should be giving all my attention to my son.” She reminds herself that self-care isn’t selfish: “I need to remind myself, and I do this often, that pouring into my own cup is pouring into him.”

This isn’t merely anecdotal – it echoes something we have been warned about: chronic kaupapa fatigue, doing the work of many, never being replenished, and ageing before your time. Whether it’s perpetual code-switching, cultural caretaking, or being asked to speak on behalf of Māori every day; there’s no respite. The signs match what Pūkenga Psychology names as depleted-mauri burnout: physical fatigue despite sleep, insomnia, irritability, loss of focus, emotional withdrawal, cynicism, and frequent headaches or illness.

On a national scale, Māori are statistically at greater risk of burnout. Research from AUT revealed that Māori staff face nearly six times the burnout risk compared to others – a consequence of bureaucratic systems, relentless workloads, and the expectation of constant connectivity. If the professional environment poses that level of threat, the compounded pressure faced by Māori students navigating colonial institutions on unequal terms is not hard to imagine. By the time burnout shows up in grades, attendance, or health, the deeper damage – emotional, cultural, and spiritual – is already well underway. Too often, the systems meant to support students are ill-equipped to recognise or respond to that kind of collapse.

When asked if the University understands or supports the realities that tauira Māori face, Te Āwhina was torn. “Yes and no. It just depends,” she says, explaining that there are some systems in place but that they can still retain an institutional feel. “I know a lot of rangatahi who have just started uni this year who aren’t getting involved in TRM, or going to the cultural support opportunities available because of the culture – [there’s an] intimidating cliqueness [to] some of those spaces.” Perhaps it's a combination of culture shock, cliqueness, and overall disconnect that keeps tauira from pursuing these support networks.

For Te Āwhina, it’s clear: “I don’t feel [that] there’s enough openness or it’s not as easily accessible as it could be,” she explains. It can be burdensome, knowing that there aren’t very many opportunities for tauira to connect with local hapū. It entails more work, more ideas, and more confrontation. “There isn’t a strong relationship there, so I think that ties in with the lack of interaction for tauira Māori who come to Otago, because the institution itself isn’t prioritising [it],” she says. “I don’t feel that relationship.”

One of the more invisible burdens is the expectation to act as a cultural representative wherever you go – in lecture theatres, clubs, and common rooms – often without the protection of genuine, culturally grounded support. As The Education Hub explains, caring for students as Māori means acknowledging Māori identities, knowledge, and experiences as valid, legitimate, and enriching to the entire learning space – not flattening them into stereotypes, or extracting value without reciprocity. Tauira Māori are frequently asked to bring their culture into academic spaces, yet those same spaces rarely meet them with the same depth of care or cultural integrity. Even recently, she reflected on an encounter in a postgraduate class filled with international students. “I made a new friend – she’s German, here on exchange studying Peace and Conflict. At the international welcome, He Waka Kōtuia performed kapa haka, and she said, ‘How genuine is this? Did the University just invite them and actually uphold its promise?’”

That comment stayed with Te Āwhina. “I thought, wow – thank you. Because usually no one says that. [We] don’t get many of the Pākehā staff or students noticing that,” she says. “My classmates were shocked to learn our real history [because] people come here thinking Aotearoa has a great partnership with Māori.” These kinds of reflections now come with clarity and a bit of distance. But there was a time, not so long ago, when the weight of navigating university as a Māori student felt far heavier, and a lot more isolating.

From Burnout To Boundaries

Recovery didn’t come quickly for Te Āwhina, and it didn’t come solely from the university system. “I don’t think when I was in the thick of it [that] I was aware of the support systems available to me,” she says. “But I did find my way.” It was a mix of time, a few good friends, and eventually a quiet walk into the counsellor’s office. There, slowly, she began the process of climbing out. “I was so scared to fully fail,” she adds. “Like, I need to get my shit together before I’m fully kicked out or something at uni.”

Her turning point isn’t defined by drastic change or putting life on hold, but rather “feeling a spark for life again.” She started noticing joy again, possibilities, even leadership. “I remember running for TRM and saying, ‘I’m going to get back on the wagon,’” she explains. “I’m going to try something I know I’m capable of. I’m going to come out of the dark.” That decision wasn’t small. “It was a really brave, scary thing for me to do.”

This is what restoration can look like, but it shouldn’t have to come after collapse. The current systems too often reward burnout, platforming unrealistic expectations and leaving Māori students to carry not just the academic load, but cultural and emotional labour too. As Te Āwhina puts it, “When you're going through it, you can't really explain to others what you're going through.” That silence, driven by stigma, shame, or fear of letting people down, often stops tauira Māori from seeking help until it’s too late.

Real solutions lie not just in self-care, but in structural care: peer-support systems, breaks that centre hauora, dedicated Māori student counsellors who understand the cultural context, wānanga with safe people, deactivating social media, and reframing that as manaakitanga to yourself. These aren’t just coping strategies; they’re acts of resistance in a system that wasn’t built with us in mind.

“Maybe that kind of rest and isolation was necessary,” Te Āwhina reflects, looking back on the stillness of lockdown. Maybe, in a world that never stops asking, the real revolution is learning to stop – and to protect your mauri before it’s gone. “Maturing over the years – I'm 25 now – I’ve learned that not only is it helpful, but it is necessary to set boundaries where needed.”

With that regrounding came a new drive – the kind that carries you into rooms you once thought were out of reach.

Personal, Political & Full of Purpose

The journey didn’t necessarily begin with a plan to run for the OUSA Executive. “Being on Te Rito was a nice stepping stone,” she says, “but I didn’t know that I was going to [be part of] an overall student body thing.” It was a friend, a former Political Rep and strong Treaty partner, who first encouraged her to run for the role, noticing the potential in her kind of leadership. Te Āwhina shared that she doubted her abilities, that “I couldn’t possibly do that,” but when she learned that Melissa Lama – then President of the University of Otago Pacific Islands Students Association – was running for OUSA President, she felt inspired. “[I thought] wow, this Tongan woman is going to run for OUSA President, for the whole uni? How inspiring.”

Te Āwhina entered the race – and when her competitors dropped out, she was stunned. What should have felt like a victory brought a strange mix of emotions. She recalls thinking, “I'm not going to deserve it. I just get handed it.” Even in that moment of success, self-doubt crept in. But it didn’t last long. “Someone said to me that they were intimidated by me,” she says. “[I thought], I need to start recognising my own abilities more.”

As the first Māori student to hold the OUSA Political Representative role, she saw the position as more than a job – it was the start of something new. “I was the first Māori Political Rep, [and] there weren’t many before me.” The mahi was demanding, but thrilling: from oral submissions to Members of Parliament about Māori students in education, to delivering local election kaupapa on campus, to coordinating with national politicians like Chlöe Swarbrick. But one challenge that seemed imminent was “trying to get more engagement with the Māori and Pacific students with politics and local politics.” It was also draining. “I definitely got burnt out throughout that year, too, which I don’t think a lot of people knew was going on.”

And through all of it – from juggling kaupapa and elected roles to surviving burnout – Te Āwhina became a māmā. Her son Noa was born the year after her OUSA term and, in many ways, his arrival sharpened everything. Now, as Noa turns two, Te Āwhina is in the early days of her Master’s journey – and just weeks away from crossing the stage to graduate in August with a Bachelor of Arts and Commerce. It’s a massive feat for her whānau. The milestones feel layered: personal, political, and full of purpose. Still, her focus on uplifting Māori hasn’t wavered. In her Master’s thesis, she hopes to centre indigenous-led solutions. “I’m a big believer in indigenous people finding the answers to indigenous issues,” she says.

Looking ahead, her focus is expansive: climate justice, diplomacy, and uplifting communities across Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa. “I hope to travel and connect a lot with like-minded people, I want to go into diplomacy, [and] I care about many social justice issues.” But alongside the global, there is the deeply personal: “Motherhood is one of the big dreams of my life. I also want to continue to follow my other dream path and find that balance.” She reflects openly on the tension that many wāhine feel – torn between ambition and caregiving, between the wider world and the one at home.

Being Built Different

Being built different isn’t just about carrying more or how well you carry it all. It’s about knowing when to lay things down – the break you don’t take will break you.

Te Āwhina’s journey through student leadership, striving for academic excellence, periods of burnout, and now juggling her Master’s with motherhood, speaks to a wider story of what it takes to navigate institutions that weren’t designed with you in mind. It’s not just about surviving the system; it’s about refusing to shrink within it. From the frontlines of political advocacy to the quiet work of healing, her experience reflects the complexity many wāhine Māori carry: leading change, holding whakapapa, and carving out a space where there wasn’t any.

As she continues forward – not in spite of it all, but because of it – her story is a reminder: being built different doesn’t mean bending to fit the mould. It means shaping something new entirely.