Long before he was a peace campaigner, a priest, or a friend of Desmond Tutu, Paul Oestreicher was an enemy alien. His family had fled fascism, seeking refuge in Dunedin – a city that offered safety, but not quite acceptance. In Dunedin, the Oestreicher family were reported by neighbours, monitored by police and even accused of signalling submarines while at the beach.

Otago University, however, has always stood slightly apart from the rest of the city – a self-contained world with its own logic and loyalties. It was here that the Oestreichers found something closer to belonging. Paul’s father, a pediatrician, was forced to retrain in lecture halls beside students half his age. His mother, a celebrated soprano, sang private concerts for students in the boarding house she ran to make ends meet. Paul spent his childhood beneath the floorboards of student life, listening to the scarfies upstairs play Billie Holiday records and try to make sense of their futures, as he quietly did the same.

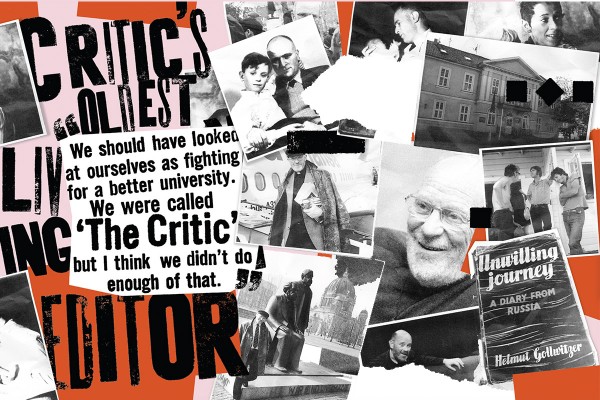

By 1952, Paul Oestreicher was no longer merely observing student life, he was shaping it as the 21-year-old editor of Critic, then still a newspaper. In his first editorial, he laid out a manifesto that now reads every bit its age: serious-minded, internationalist, and conspicuously earnest beside the “Best Places to Shit on Campus” surveys of the magazine today.

“Critic,” he wrote, “should make us realise we are a part of a national and worldwide fellowship of university people. We as a student body are shamefully ignorant of the subject that affects us more than any other in the present-day world. We are not interested in why the world is drifting into catastrophe.”

That editorial marked the beginning of a lifelong engagement with global suffering. Over the decades, Paul’s work would take him into some of the twentieth century’s most volatile conflicts. He campaigned against apartheid, for nuclear disarmament, for women’s ordination, for the release of political prisoners, all while as he once put it, trying not to “disappear” somewhere in Siberia.

What first drew me to Paul – unsurprisingly – was his résumé: Chair of Amnesty International, BBC Radio producer, founding member of Jews for Justice for Palestinians, vice-president of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. In 2022, he was awarded an OBE for his lifelong peace and human rights work (a title he now shares, somewhat improbably, with the likes of David Beckham and J.K. Rowling).

When I arrived to interview Paul, now 94, in his book-lined Wellington apartment, his Wikipedia list of accomplishments became secondary to the story he told about himself. His life could easily fill a book, one Paul insists he’ll never write: “For some psychological reason, I couldn’t do that.” However, there is now hope of a forthcoming biography.

I began our interview with polite curiosity – “Have you kept up with modern Critic at all?” – and ended it, without irony: “Do you believe in an afterlife? Or do you think there’s nothing more?” Between those two questions, and a teapot growing cold between us, Paul told me his life story.

The War

Paul Oestreicher was an only child, born in Meiningen, Germany. His childhood had all the outward signs of comfort: a yellow townhouse with tall windows, a father who ran his medical practice from home, and a view across the street to the Staatstheater, where his mother sang Lieder and oratorio.

But it was a lonely life. He had no friends, not because he was shy or strange, but because he was held to be Jewish. In 1930s Nazi Germany, that was reason enough.

His education lasted just six months before the Oestreichers were forced to leave town in September 1938. Paul Snr’s medical licence had been revoked; Emma had lost her position at the theatre years earlier for being married to a Jew. “Her professional career ended the day [Adolf] Hitler came to power,” Paul recalls. With no income, they couldn’t pay the rent. Their landlord threatened to throw their furniture onto the street. By some stroke of luck, their BMW remained untouched: their only means of escape.

Paul was sent to stay with an elderly relative while his parents went into hiding, never sleeping in the same place twice. “The problem was, which country is prepared to take us?” Paul remembers. “Most countries had closed their doors to Jews.”

New Zealand was no exception, taking in just 1,100 German Jews – a reluctant gesture, made under British pressure. Even then, they weren’t officially recognised as refugees. Applicants needed capital, job offers, or skills deemed useful in order to immigrate. “If you were a poor Jew with no connections outside Germany, your chances of survival were very small,” Paul reflects. “My parents got in simply because they had the right friends.”

Growing Up

Paul Snr’s medical contacts helped the family reach New Zealand – a move that almost certainly saved their lives. But his credentials didn’t transfer. In 1939, they settled in Ōtepoti Dunedin, home to the country’s only medical school. “My mental concentration camp,” his father joked, “was having to pass university exams at the age of forty-five, in a language I’d never learned.”

For a time, Emma’s career seemed more promising. In Dunedin, she became a celebrated concert singer, performing at the Town Hall and praised as the “German mezzo soprano”. After everything she had given up to stand beside her husband and child, she was back on stage – applauded, admired, even locally famous. And then, just four months later, it was taken from her again. When New Zealand declared war on Germany, she was barred from performing, not by the Nazis she had fled, but by the community she had fled to. “My mother wasn’t allowed to sing again publicly, this time because she was German,” Paul recalled. “So she had a double whammy. Her career was literally wrecked twice by world politics.”

The idea that Paul’s family were Nazi spies struck some in the community as darkly comic, including the local ‘Aliens Officer’ assigned to monitor Axis nationals. “He became a good friend,” Paul says. “He’d call and say, ‘Madam Oestreicher, I’ve had another complaint. May I visit tomorrow?’ ‘Yes, sir.’ ‘Then please bake some of your lovely German apple cake.’” He came, ate, and told the neighbours he’d done his job. “Some people had a sense of humour. Some knew the idea we were spies was absurd.”

Despite some lingering stigma after the war, Paul describes himself as a happy boy who made friends easily. One of those friends was Louise Harris (later Petherbridge), the daughter of the man who sold the Oestreichers their first family home. “We were both, I think, 11 or 12, and we were friends from that day.”

It was Louise who first introduced Paul to Anglicanism, the faith in which he would later be ordained. “We used to go cycling together. I remember one day she said, ‘We’ve got to go home early tonight because I’m going to church tomorrow morning.’ I said, ‘Hey Louise, I’ve never been to an Anglican service. Can I come with you?’ She said, ‘Of course you can.’ I went, and I never looked back.”

Louise and Paul were very close, but he insists there was nothing romantic about it. “I always wondered, 'Why was she different?' [...] Her father once told me Louise said I was the only boy she's ever met where you can talk and talk and talk [laughs]. And we did.” During their time at Otago University, Louise confided in Paul that she was a lesbian – a revelation that would become Paul’s first introduction to what it meant to be gay. “We were so close, Louise and I, that she let me in on all her secrets [...] [Her] life was very important to me and [the source of] my real understanding of the gay community long before it was current.”

University

In 1949, Paul and Louise both enrolled at the University of Otago: he in politics, she in theatre. Neither of them knew they’d end up famous in their own fields – Paul as a human rights advocate with an OBE to his name, Louise as one of New Zealand’s most celebrated thespians.

Paul lived at home with his parents during university but was heavily involved in campus life. He became, in his words, “a kind of left-wing campaigner”, active in the Student Christian Movement (a big deal in those days) and increasingly involved in student politics through the New Zealand University Students Association. One of the formative experiences of his early adulthood, he says, came not from lectures or textbooks but the annual student congress at Curious Cove.

“There’s no such thing now,” Paul reflects. “It was so stimulating. The brightest students from all the universities got together in a cove in the Marlborough Sounds. [It was] originally a camp for American soldiers during the war. The students bought it. It belonged to the Students Association.”

The congresses, famously photographed by Ans Westra in the 1970s, captured a moment in New Zealand student culture when degrees weren’t just a means to an end – the end itself was open to question. The photos show students arriving by boat, dancing barefoot on wooden floors and sunbathing half-naked in loose clusters. The mood was free, in every sense. “People did sleep with each other very easily,” he adds, laughing. “We weren’t arguing until five in the morning very often.”

Paul, who served on the national organising committee, helped choose which lecturers to invite. “We invited the most stimulating of our teachers to come and speak informally, in a camp holiday mood. We had fantastic lectures. I think I learned more at those camps than I did at university at all. That’s where you meet people you totally disagree with.”

Critic

In 1952, Paul became editor of The Critic, though he can’t quite remember how. “I think I was already keen to write, but I don't think the job was ever advertised. It was all very informal.” The Critic office was housed inside what’s now Marama Hall, in the old Clocktower complex. “It was always a bedlam of mayhem,” he says, describing loosely organised volunteers, some friends, others just showing up and asking to join.

The Korean War was the big issue of the time. Unlike Critic today, which mostly avoids international coverage – in part because global news is now just a scroll away – 1952 Critic was one of the few ways students encountered global affairs. Although the likes of The Guardian was still the go-to, even then. Paul admits he often reprinted its articles and those of other newspapers without asking. “Simply, I often cheated without permission,” he laughs. “I thought, ‘We’re a student paper, nobody’s going to make a fuss about this.’”

But someone did. The Otago Daily Times (ODT), which printed Critic at the time, refused to run an issue that included a reprinted article about germ warfare in Korea. “I refuse to print it,” ODT editor John Moffett told him. Paul pushed back. “I said, ‘John, you refuse to print this. I protest. I think I have the right to. If you refuse to print it, I will make that public. There will be an empty front page.’” That week, Critic went out with a single word on the cover: CENSORED.

Eventually, they negotiated a compromise. Paul agreed to run an opposing article beside the original, refuting the allegations as propaganda. “In fact, history has proved it was true.”

While the consequences of global injustice were still present on Otago’s campus, it went largely unchallenged by Critic. He recalled one lecturer in German, Dr Felix Grayeff, a German Jewish refugee (who contributed articles to Critic) but was never promoted within his department. “He was far superior in his knowledge to anybody else in the German department. But he was just a junior lecturer.” Eventually, Grayeff emigrated a second time: to the UK. Paul says antisemitism was the cause of it; something that lingered in parts of the university after the war.

He remembers much of it was due to a senior staff member in the language department.. “She was an awful anti-Semite.” According to Paul, she had openly admired Hitler’s Germany and had written about it before the war. “When the war started, she would of course change her tune… But I don't think she had a change of heart.”

Paul regrets that Critic never called out authoritative figures like her directly. “We never attacked any person for any reason. We should have been fighting for a better university. I think we didn’t do enough of that. Looking back, we were called Critic, but we probably weren’t critical enough.”

Asked what he thinks of modern Critic, Paul expresses disappointment. “The whole tone has changed,” he says. “It doesn’t surprise me, but it makes me somewhat sad. I’d like to see more real intellectual debate, the climate now… students aren’t really [actively] political at all.” Still, he recognises students now face pressures his generation didn’t. “Now everything is very competitive. Students don’t have much time. So when they do, they go and drink,” he added, laughing. “Which is okay.”

It’s arguable, however, that Paul himself helped pioneer the irreverent tone of Critic and student media that followed. In 1952, he commissioned the first ever sex themed issue, later published by his successor John Irwin and other student papers around Aotearoa. “That special issue was the beginning of the sexual revolution.” Paul remembers. “It wasn’t very bold – but even to talk about sex publicly, it was not yet done.”

The Book That Changed His Life

In 1953, Paul Oestreicher had left Critic behind and moved north to Victoria University to complete a master’s degree, something Otago did not yet offer in Political Science. One afternoon, he wandered into a Wellington Christian bookshop and stumbled across a text that would go on to define the course of his life: Unwilling Journey: A Diary from Russia, by Helmut Gollwitzer.

Gollwitzer had been a prominent German theologian and outspoken opponent of the Nazi regime. Drafted into the German army against his will, he was captured by the Russians and spent six years in Stalinist prison camps. The book was his diary written during that imprisonment. Reading it gave Paul something his study of politics alone hadn’t offered: a framework for understanding faith in the face of totalitarianism.

The book led him to choose a dissertation topic on the history of conscientious objection to the Second World War – a somewhat controversial choice in 1950s New Zealand. His supervisor, Major General Sir Howard Karl Kippenberger, had commanded troops in North Africa and Italy, and lost both his feet at Monte Cassino. The pairing of a pacifist student and a decorated general could easily have been adversarial, but instead became formative. “This young pacifist that I was,” Paul later said, “became a good friend of the general.” From that friendship grew a conviction that would remain central to his life: that “the very fact of war is a crime, but soldiers are not criminals.”

After finishing his masters, Paul’s intellectual focus began to shift. “To understand politics is one thing,” he reflected, “but to understand why we're here, human existence and its meaning... that’s a spiritual question.” After completing his degree, he applied for and received a fellowship to study at the University of Bonn in West Germany. His new supervisor would be none other than Gollwitzer himself, now a professor of theology at Bonn, specialising in the relationship between religion and the state. “Amazing chances,” Paul reflects. “You’d never plan it that way. It just happened. The rest of my career was built on that foundation.”

However, the idea of returning to Germany was troubling at first. “Germany was the country that expelled us. That killed us [other] Germans,” he recalled. However, Paul felt that reconciliation was essential for his own integrity: “If I was a decent Christian, I had to learn to accept Germans as my fellow human beings, and not hate them.”

When Paul arrived in Bonn in 1955, his classmates, he observed, were still living in a “totally different mental world” having been raised by Nazi parents and seemed unable to acknowledge the past. “They didn’t know how to cope with me. They never asked me anything. I almost felt I was an embarrassment to them.” In his view, Germany’s cultural shame at the Holocaust came years later. “It's very strange how history works. The German student generation in the late sixties and seventies were desperately ashamed to be German... But it took 15 more years for that to happen.”

Paul felt disconnected from his peers and instead became close to the faculty. Many of his lecturers had been political prisoners themselves. “Just about all the professors… had suffered under the Nazis with [the Jews]. They could understand me completely.”

Career

Paul’s first post after graduation was at BBC Radio, producing programmes on church and society. Politically conscious and grounded in faith, it was a fitting continuation of his journalism career post-Critic.

By the 1960s and 1970s, Paul’s work had pivoted to freeing political prisoners. He was a founding member of Amnesty International and later became its chairman, a role that took him into some of the world’s most repressive regimes, landing his name on a South African blacklist for his outspoken opposition to apartheid. But Paul was not easily deterred. He secured a British passport and listed his occupation as “British clerk”. “Clerk,” he explained, “is the medieval word for priest, but I didn’t expect the South Africans to pick that up.” At the border, an officer scanned his name on a blacklist, hesitated, and waved him through.

Inside South Africa, Paul decided it was better to own up to his presence than risk being exposed. He went straight to the Minister of Justice. “If he refused to see me, it would have been a public scandal,” Paul recalled. “So they let me stay, but they watched my every step.” Under surveillance, he visited families of political prisoners, helped secure releases, and compiled evidence of torture. “Getting people who should not be imprisoned out of prison was my job.”

Paul’s work with Amnesty International prepared him for what came next. As Secretary of the Committee for Relations with the Communist Countries of the British Council of Churches, Paul negotiated for the release of dissidents across Eastern Europe. “I was expelled from Czechoslovakia and not allowed into Russia. There were always ways around the secret police,” he said. “In the Stalinist period, I could have ‘disappeared’ somewhere in Siberia.”

Paul believed he was spared because he never met hatred with hatred. His principle was simple: treat every person – even those enforcing the systems he opposed – with dignity. “I always said, ‘I’m not your enemy. I respect you because you’re a fellow human being.’”

The most personal of those negotiations came in East Germany, where a New Zealander named Barbara Einhorn had been arrested for her work with a group called Women for Peace. “I helped negotiate her release and ultimately – 18 years later – married her,” Paul laughs. “There won’t be many cases of people who find their future wife in prison, help get them out, and marry them.”

Though his activism often took him into politics, Paul remained equally committed to reform within the Church. He believed that any institution claiming moral authority had to confront its own injustices first. For the Anglican Church, that meant ending its exclusion of women from priesthood. “It happened far, far, far too late, but it did happen in the end.”

One of the curates in his parish, Elsie Baker, was barred from ordination. Paul remembered telling her, “You’re not yet a priest, but you will be one day. While you’re on my staff, help me run the parish anyway.” For years, Elsie ministered unofficially. When the Church finally changed its law, she was 83 and long retired. The Bishop of Southwark came to see her and said, “Elsie, I’m afraid I can’t make you a priest.” She smiled and said she was far too old, and simply happy for the younger women who’d finally be recognised. “No,” the Bishop replied, “you’ve misunderstood me. God made you a priest a long time ago. I can only confirm it.” At 83, Elsie Baker became the oldest woman in England to be ordained. “The Church caught up,” Paul says, “with what God already knew.”

In 1984, Paul’s old friend and university contemporary, Paul Reeves – then Bishop of Auckland and soon to be New Zealand’s first Māori Governor-General – invited him to dinner in London. Reeves had just been knighted and wanted Oestreicher to accept nomination as Bishop of Wellington. Paul agreed, reluctantly. Though he was then elected by a large majority, conservative factions within the Church vetoed the appointment, Conclave-style. “Thank God,” Paul laughs. “Trying to get people out of prison was much more me.”

Paul’s refusal to separate faith from conscience sometimes put him at odds with political orthodoxy. One of his most controversial stands came as a founding member of Jews for Justice for Palestinians. “For the first half of my life, the German in me was deeply ashamed of what Germans had done to Jews. But when I saw what the Israeli state was doing to the Palestinians, the Jew in me was deeply ashamed of what Jews were doing to Palestinians.” He rejects any accusation of antisemitism: “I feel Jewish. But I’m ashamed of what the state of Israel is doing.”

Even in his nineties, Paul remains outspoken – opposing nuclear power, supporting the 2024 hīkoi against the Treaty Principles Bill, and still occasionally running afoul of the censors. “I sent a good article on Palestine to the Archbishop of Canterbury. Microsoft wouldn’t even send it,” he alleged. “The system decided it disapproved.”

Thoughts on Life

Underlying every position Paul held – priest, journalist, activist – was an attempt to reconcile the world’s moral failures. He reflects on the state of humanity today with sobering clarity.

"I don't think people themselves are getting worse. But collectively, we are in a very, very dangerous situation. Everything else in my life that I've talked to you about is my past, it doesn't exist anymore – well, it does, but at 93, you can't put your weight and influence behind things in the same way. You have to focus on the essentials. If people ask me what matters most, I tell them this: I’ve scrapped all my formal connections to organisations, except one. I’m still Vice President of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. At 93, that’s the only role I still hold.”

Power today, Paul says, is embedded in weapons on a scale human history can’t comprehend. Unless those in power have the “intelligence and skill” to steer the world away from disaster, the chances are not good, he warns. “Especially with people voting the way they do. I mean, look at the world of Trump, Netanyahu, and Putin […] I don’t pretend to understand it all, but it makes me very pessimistic.”

With the conversation veering in a philosophical direction, I ask him if he believes in the afterlife, a heaven that would surely receive him. Death, Paul replies, is not something that frightens him. Despite his faith, he admits he has no idea what lies beyond.

"It’s a mystery. I don’t think there’s nothing, but I also don’t think there’s a place called heaven or a place called hell. But what we stand for – that’s a reality beyond ourselves. Religion is an attempt to answer that question. A very unsuccessful attempt, I would say. There are many different religions, all trying to do the same thing: explain our existence. And some even think they can explain what happens after death. But I don’t think anyone can. We haven’t got a clue.”

Paul describes himself as a “happy representative” – though not a typical one – of two branches of Christianity: Anglicanism and Quakerism. But his daughter who is close to Buddhism, he says, is just as likely to be right about the afterlife as he is. “We simply have different experiences of ultimate reality. And some people have no experience of that at all. Many have abandoned questions of belief entirely. I think living decently with our neighbours, day by day, is enough. Maybe that’s all that matters. I don’t think being religious makes me better than others. And I certainly don’t think religious people are inherently better than others.”

He sees the same longing for meaning in those who reject religion altogether. “Karl Marx said religion props us up – it gives us a sense of purpose that makes life bearable. But to him, that wasn’t enough. Marx believed we have the power to make a revolution and improve things ourselves.”

But no ideology lasts forever, Paul muses. “The Nazi one collapsed very quickly. The communist one took a little longer, but it met the same fate. And I think the present state of Western capitalism – it’s headed the same way. It will collapse. It is already in crisis. The economists don’t have the answers for ordering the world in a way that gives dignity to everybody. Capitalism does not, nowhere near. It’s not even a defined ideology, which is why it’s flexible enough to survive for now. But nothing is forever. Socialism, I think, is a better ‘ism’ than capitalism. But it’s all relative.”

Sitting with his words, I ask whether, if he were young again, he would still choose to bring children into the world.

"I think and feel that we are meant to exist as part of creation,” he replies reassuringly. “This world, as we know it, is very small compared to the whole wider sphere of existence – something much bigger than we can imagine. Within it, we are a tiny fragment.”

And yet, Paul admits, the rest of the animal world seems far more capable of living with itself than we are. “The destructive part of us is just as real, just as powerful, as the constructive part. So, if you like, there’s a cosmic battle – a struggle between good and evil. And I won't see the end of it. Not even close. Anything beyond the next ten years is not my world anymore. And I certainly don’t want to live to 110.”

Then Paul pauses and smiles softly. “Well. I think we've covered a heck of a lot of ground. So, do with that what you will.”