Over forty years ago, passionate residents of a small settlement, just 20km along the coast from North Dunedin, founded the Independent State Aramoana. While it never became anything close to an genuine independent nation, they fought tirelessly against the government to prevent an aluminium smelter from destroying a pristine natural environment. Through their hard work, determination, and more than a bit of luck, they won.

Aramoana is a beautiful place. From atop its rocky heights, hardy grasses and rugged trees stretch far away below. Salt marshes soak up the tide. Shattered cliffs and steep dunes are signs of a slow but constant battle with the sea. And while its hills reflect a struggle against the elements, the small settlement has weathered a greater storm: one of metal, and money, and a man named Robert Muldoon.

Throughout the 70s, Aramoana fought against the government to prevent an aluminium smelter from destroying an ecologically important wetland and a home to locals, particularly local iwi. This battle came to a head when the State of Aramoana declared independence in 1980. Within two years the government proposal fell apart, and, having achieved their goal, the Independent State of Aramoana reintegrated into NZ.

In the 1970s the NZ Government realised that exclusively exporting wool and lamb to the UK was not a diverse basis for an economy. National leader Robert Muldoon, who maintained power in 1978 through the tried and true tactic of accusing all of his opponents of being communists, introduced the ‘Think Big’ infrastructure campaign to refresh the economy. By passing the National Development Act, Muldoon empowered the government to all but ignore the concerns of local stakeholders in developing projects of ‘national importance.’ Development of the Aramoana aluminium smelter was one such project.

The Save Aramoana Campaign (SAC), which was formed in 1974 when a smelter was first proposed, now faced a Government with almost unlimited authority to build whatever they wanted. The group was formed not only to preserve the unique beauty of the area but also to protect the community of Aramoana as a whole. The government disregarded Māori concerns that the smelter could put burial sites at risk. In their submission on the smelter plans, local Māori leaders were forceful, stating “We will not countenance violation of the dead, nor consent to any further destruction of our history that lies in the land.”

At the time, there weren’t many limits on what could be done with land. With no Resource Management Act, the concerns identified by early exploration of the site were not the terrible impact of aluminium smelting on the environment but instead whether or not the sandy ground was capable of supporting the heavy machinery needed for the smelter. To make things worse, the land at Aramoana was owned by the Otago Harbour Board and only on lease to the locals. Legal challenges to the development ended in failure. The main tactic of the SAC became to shift public opinion against the proposed development.

To achieve this, SAC based their non-violent tactics on those of the Orakei Māori Action committee who, in 1977, occupied Bastion Point during a dispute with the government over rights to the land. A massive media campaign was launched at local, national and international levels to raise awareness of the smelter. Publications about Aramoana reached newspapers as far away as The Guardian in the UK and the Wellington Art Gallery held an exhibition titled Aramoana: Tapu Land, which featured work from legendary Dunedin artist Ralph Hotere. Support also came from poets such as Cilla McQueen and Brian Turner. However, despite national concern about the project, Aramoana was soon confirmed as the site for the smelter and eviction notices were issued to residents forcing them to choose between compensation or resettlement.

With their backs against the wall, local residents crossed their fingers and threw a Hail Mary - and it worked. They declared the Independent State of Aramoana (ISA) on 23 December 1980. The SAC stated in grandiose language “the area known as Aramoana and Te Ngaru… does hereby Secede and Declare itself Independent from the Province of Otago and from the Dominion of New Zealand. This action has been forced upon the Citizens of the Area because of the unreasonable and undemocratic actions taken by the governing bodies of Otago and NZ. Be it known that all people wishing to enter the area must apply for the appropriate documentations.”

While largely a publicity stunt, the declaration was backed up by the production of flags, passports, stamps and even a mock tax declaration form, all for sale to raise money for the movement. To sell merchandise and raise awareness, the SAC operated a ‘travelling embassy’. Overall, the fundraising efforts are estimated to have raised $500,000 in today’s money. The declaration also demonstrated lengths the SAC was prepared to go to to see that the smelter was never built.

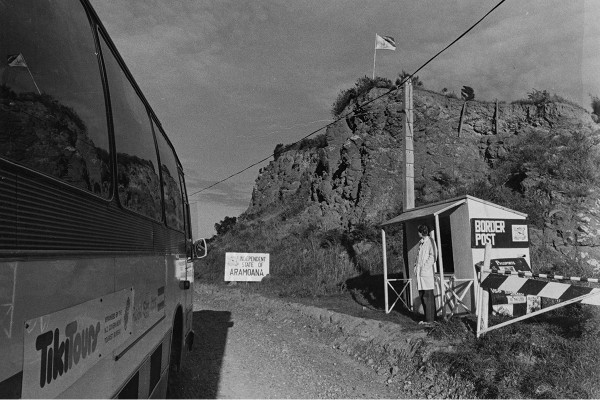

On the roads leading into the ISA a road block ‘border post’ was established in case construction vehicles ever appeared. A handbook issued by the SAC suggested that those manning the border post were to greet newcomers with “Welcome to the Independent State of Aramoana. We have declared this area independent to stop a smelter being built here. Do you have any smelters concealed in your car?”

The government nonetheless seemed determined to proceed with the project they viewed as essential to bringing New Zealand out of years of economic downturn. There was also considerable public support for the smelter from many in Dunedin who believed that it would usher in a new age of economic prosperity for the city.

Businesses and artists who opposed the smelter sometimes had their windows smashed in and buildings vandalised. Mayor Cliff Skeggs, an avid supporter of the smelter, claimed in a speech that "the problem is that many of those involved in the anti-smelter movements are pathetic malcontents looking for a cause – any kind of cause – to fill otherwise meaningless lives.” Further, opponents to the smelter scheme were vilified as ‘North Islanders’ and hypocrites for using aluminium products but opposing an aluminium smelter. Skeggs also pointed out that, because of the links of many of the protesters to the University, the University itself was “a real problem.”

In April 1981 it was confirmed that residents of Aramoana would be evicted the following year. SAC’s occupation appeared to have failed. But just as the project was about to get started, a major company in the proposal pulled out. The Independent State of Aramoana’s second stamp issue pamphlet describes the withdrawal: “Alusuisse, the Swiss multinational giant which was to provide the technology for the project, withdrew from the smelter consortium.”

Despite repeated claims from the National Government that the project would continue, nothing further happened. When Labour was voted into power the government no longer wanted anything to do with massive, centrally planned aluminium smelters. The Save Aramoana Campaign was victorious because, as their pamphlet stated, the project could not proceed “due to a combination of the gloomy future for the world aluminium market, the direct pressure on them from anti-smelter groups, and the weight of informed public opinion which stopped the Government lowering its electricity price for the project as far as it would have liked… VIVÉ ARAMOANA.”

Overnight, the residents of this small settlement became artists, activists, and amateur ambassadors of the Independent State of Aramoana. Through their toil, plans for a smelter at Aramoana eventually fell by the wayside, and with it so did the ISA. The memory lives on, in art and politics, to this day.