In March, I got a Google invite from the University of Otago.

2pm – 4pm.

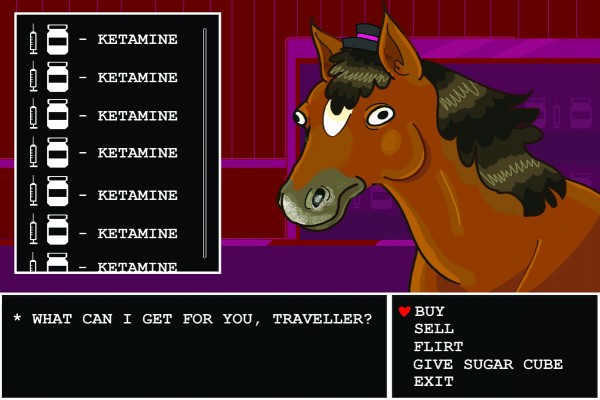

KETAMINE.

Ketamine is an anaesthetic, known for its usage on horses as a tranquilliser. It also gets you fucked up and therefore is illegal for recreational use. Ketamine can be found on campus, but only if you are doing the official study with Dr Paul Glue. His study aims to cure depression. I discovered it from a sponsored Facebook post, right beside a Wish ad for willy warmers. I’d tried a handful of different medications and had given up, raw dogging reality in a serotonin-deficient limbo, so I filled out a preliminary depression questionnaire and passed with flying colours.

The sesh organiser is an Otago Uni Professor of Psychological Medicine and pioneer of weird and wacky treatments for miserable sods who hadn’t much luck with standard antidepressants. According to Dr Paul Glue, the treatment works for about two thirds of those who try it.

A few meetings later I was sat in a La-Z-Boy, a gooey brain cap slapped onto my head, looking bald and sexy. After blinking at a wall for ten minutes to record my resting brain activity, a vial of ketamine was taken from the fridge. It was sitting right beside some yoghurt and orange juice (no pulp), then injected into my arm.

“How are you doing?” Dr Paul Glue asked me after a couple of minutes.

“I’m good,” I responded. “I’m not even feeling iiuuruuguughhhhhhhghh.”

The world’s frame rate dropped. I thought very hard about moving my hand but it lagged behind; it looked grotesque and waxy, like the skin on cheese. I closed my eyes. That was a bad idea. I fell through my entire life and out the other side into death. It must have looked horrible, because a doctor tried to console me by reading a passage from her book: Prehistoric wombats were over six feet tall. This was too much. I threw up everywhere.

I left with crusty hair and forbidden knowledge of the universe, wishing that I had listened to Harold the Giraffe. But my depression had briefly subsided. Despite the rancid experience, it felt pretty okay afterwards. I staggered down George Street and didn’t care that I looked (or smelled) like a goblin. I made mashed potatoes for dinner. They burnt, but I didn’t even cry.

Standard antidepressants take around 4 to 6 weeks for mood to improve, and only a third of people totally ‘recover’. Ketamine was hitting the feel-good part of my brain within a couple of hours, and I enjoyed a full week of functioning until the next dosage.

Ket was first experimented with for antidepressant purposes around the year 2000, when a group in the USA gave it to a group of 8 patients with treatment resistant depression, for what sounds like no real reason except a bit of a laugh. To their surprise, it improved their mood. A bigger study was done with similar results, and Paul decided to have a go as well. He’s tinkering with other internalising disorders, too, those which manifest inside of a person -- severe anxiety, OCD, PTSD, even injecting an arachnid-phobic patient with ketamine and throwing them into a horrifying virtual reality world full of spiders. These are all linked by neuroticism, a personality trait where stressful circumstances are often met with negative emotional states. He wants to understand what links these neurotic disorders together and is looking for biomarkers (physiological changes) in the brain that are associated with ketamine responsiveness, figuring out the best way to administer it. One of these methods includes slurping up ket with a cup of orange juice, hence the contents of the fridge. The yoghurt was probably just a snack.

Dosing uni students with ket sounds a bit dodgy, but Paul swears it’s legit. As an academic, he can research whatever he wants so long as the ethics committee agrees. Good clinical practice states that worthwhile research involving humans requires informed consent, relevant experience, good safety monitoring, and appropriate publishing of findings.

Depression feels hopeless at the best of times. When fluoxetine or sertraline don’t help, it feels even worse. There haven’t been many new antidepressants on the market since the first ones were discovered in the late 1950s; the new ones have fewer side effects, but they’re no more effective. Eventually there is a point where you say “fuck it, let’s do some horse tranquiliser from a Facebook ad”, and it turns out horse tranquiliser isn’t so bad. Paul thinks that an educational process needs to be rolled out; a national letter to help psychiatrists identify and treat their patients. If it worked, ketamine could be a ground-breaking treatment for the 650,000 adults diagnosed with depression in Aotearoa.

There’s a pretty significant barrier that’s standing between having some novel treatment available and seeing it used safely in practice, though. Ketamine has a stigma. Paul grimly recalled Trainspotting-esque images of black markets, of 1980s punks raiding veterinary clinics to get plastered. Don’t even think about self-medicating through your dealer. It might be ketamine, but it’s probably something more sinister, and likely won’t be administered safely. Paul does regular checkups to avoid ketamine’s side effects, namely memory loss, executive motor function and bladder issues. He hasn’t seen any of it yet. People are getting a single dose once or twice a week for several months over the course of treating their depression. Irresponsible recreational usage can be dangerous and only hurt ketamine’s image further. “I’d hate to lose something that’s potentially as important as [psychoactive drugs] where really, we have pretty sucky existing treatment. If we lose the ability to use that therapeutically, that’s a huge loss,” he says.

Ideally, ketamine would become a well-established antidepressant over the next 5-10 years. A nasal spray in the US has been approved by the FDA but it’s pricey, at $1400NZD for a single dose. It’s still in the baby stage of becoming standard treatment. Doctors and researchers like Paul are working hard to help those who otherwise feel utterly unfixable.

The question still begs, however: does Paul ever dabble in his own supply?

“No.”

Sure thing, Dr Glue. Glue → horses → ketamine. Got em.