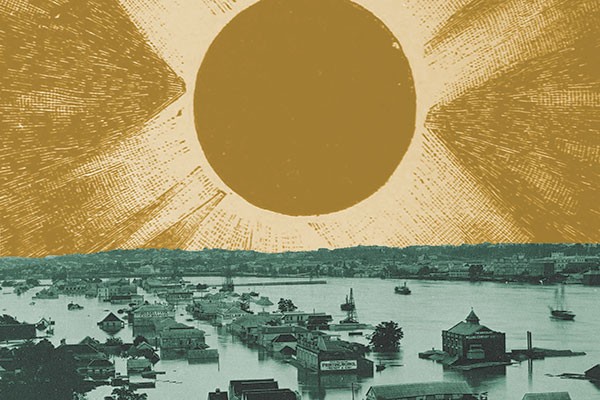

As record-breaking levels of rain fell in Dunedin on 2 June 2015, South Dunedin quickly began to resemble an Arctic Venice. Large canals divided streets. Those without a kayak or a sturdy set of waders were left to ponder indoors on what the hell was going on outside. Meanwhile, further north in Studentville, most occupants were blissfully unaware of just how bad the pandemonium was in the southern city. As the rains subsided, the wider Dunedin area was back to business as usual, but South Dunedin residents faced the challenge of cleaning up the mess the floods had left behind.

Over a 24-hour period between 4am on the Wednesday and 4am on the Thursday, 175mm fell. That’s the equivalent of an average two months of rainfall in just one day. The Southern Motorway resembled a flowing river as residents commuting into the city were trapped on the side of the road. Many were quick to link the event to our generation’s environmental elephant in the room: global warming.

The vast majority of scientists (not just climate scientists) in the world accept the reality of climate change. As Al Gore continues to play the boy who cried wolf, climate change deniers still refuse to accept this inconvenient truth. This could be compared to creationists rejecting evolution. But a small number of unknowns about a theory do not falsify it. That’s how the scientific method works: a scientific theory is the best explanation scientists have developed at a given time, until it is falsified and a more convincing argument is formulated. The vocal minority of global warming deniers tend to exploit these grey areas along with scientific complexities in climate data. So, for the time being, the large volume of scientific evidence about climate change suggests it is real.

So what exactly is global warming or, in this instance, climate change? Think about it this way: Climate is what you would expect to see, and weather is what you get. Weather describes the short-term conditions of the atmosphere. Climate on the other hand describes the long-term averages of weather in a location. So, climate change or global warming describes the change in global climate patterns driven by increased levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide. It’s important to note here that climate change is used scientifically as a more generalised term embracing both natural and anthropogenic (human-created) effects. Global warming, on the other hand, focuses solely on anthropogenic effects.

The Green party, and a lot of social commentators, gave a response to the Dunedin floods that closely resembled the Bloomberg Businessweek’s famous Hurricane Sandy cover: “IT’S GLOBAL WARMING, STUPID”. Hurricane Sandy struck New York in 2012, killing over 100 people. In the chaos that ensued, the Bloomberg Businessweek ran the controversial headline. The feature article acknowledged the risks of linking weather events to global warming. The article described the hurricane as an unprecedented, earth-shattering event with “weather on steroids”, which should prove there can no longer be room to deny the reality of global warming.

The Green party was also quick to paint a picture of the flooding in relation to the National government’s disconcerting lack of efforts to reduce our nation’s emissions. The Greens’ local government spokesperson remarked, “the flooding in Dunedin highlights that the National Government needs to stop being the problem and start being part of the solution on climate change”. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) editor and professor, Blair Fitzharris, has said that Dunedin will face more extreme weather events as climate change continues. We can hardly argue with Fitzharris’s predictions. And the Green party’s comments blaming the rainfall on climate change were probably intended to publicise global warming in New Zealand.

As the media continued to report on the aftermath of the flooding, it remained contentious whether the floods were actually related to global warming or not. We already have a good understanding of how New Zealand will be impacted by sea-level rise. The National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA) has reported that New Zealand is now a degree warmer than it would have been without climate change. Our rainfall and drought extremes and the frequency of risks are changing as a result of climate change.

The DCC labelled the event a one-in-a-100-year flood. So, based on these tremendous temporal scales, can we attribute the floods to climate change?

Dr. Nicolas Cullen, a University of Otago climatologist, says we can’t attribute this flood to climate change. Cullen cited temporal variability to explain his reasoning for not associating the events with climate change. If these events were happening more frequently, we could associate them with climate change.

Another scientist at the University of Otago’s Geography Department, Dr. Michael Hilton, gave a little more insight. He agreed with Cullen’s comments, adding: “You can’t take any event and point it to global warming. It’s trends in climate that are demonstrative of global warming. Trends that can’t be explained by natural phenomenon, but more importantly can be explained by anthropogenic phenomenon.” Hilton also expressed doubt about the way return periods or recurrence intervals are represented in the media. Return periods, such as a one-in-a-100-year storm, express that over a long timescale such a flood will occur on average once every hundred years. The problem with these probabilities is that we don’t have enough quality data to confidently make these predictions, and the world, especially under the influence of global warming, is a constantly changing and unstable place. These kinds of probabilities are often inaccurate for these reasons and skew the public’s perceptions of weather events. This kind of media skewing was evident following June’s floods.

Underlying the global warming debate in the media following the flooding in June, a more threatening issue sat quietly and relatively unaddressed, an issue that is more than likely the problem: South Dunedin’s groundwater. South Dunedin was once a marshy intertidal estuary. Picture a flat, shallow estuary like the one at Blueskin Bay (just north of Dunedin) — this is what naturally made up the flat areas of South Dunedin behind the sand dunes of St. Clair and St. Kilda. The low-lying land was slowly reclaimed and built up with sand taken from the nearby dunes. If you dig down in any backyard in South Dunedin, you will find marine muds that were laid down to build up the surface.

The water table now lies extremely high, typically about half a metre below the surface of the ground in South Dunedin. Council studies have demonstrated that groundwater is very shallow and fluctuates with sea level. As Hilton puts it, “as the tide goes up and down, the groundwater goes up and down. And that fluctuation extends over a kilometre inland”.

This rising and falling of groundwater with the rising and falling of the sea isn’t to do with the exchange of water. While groundwater and sea water sit very close to one another, they are two separate bodies of water that do not meet or mix together. The dual fluctuations are explained by the changing pressure exerted by the ocean on the open coast when the tide rises and falls. As the tide rises, it places more pressure on the coast, and the groundwater rises in close unison. When the tide falls, the pressure decreases, and the groundwater falls in close unison. There are even anecdotes about building foundations having to be poured at low tide in South Dunedin to avoid groundwater sitting close to the surface.

After the June floods, the council responded to a lot of questions. People suggested the drains were blocked and that water wasn’t able to escape the area. Hilton shed light on these concerns explaining: “Basically it is a very low-lying area which has always flooded when it rains heavily. It’s just not possible to drain enough water and, when you have a high rainfall event corresponding with a high tide, that then limits how water drains away.”

So what relevance does this issue have to flooding and global warming in Dunedin? Along with increased rainfall and cyclonic activity as predicted by NIWA, a major issue is the effect sea-level rise will have on groundwater in South Dunedin. The sea level is currently rising at a rate of 1–2mm per year and, according to Hilton, there is “total confidence about the sea level and it’s just a question of how much it’s going to rise, not whether it will”. As the sea rises and is closer to the coast, greater pressure is put on the groundwater, causing it to rise too.

Last year, the DCC commissioned engineering firm Beca Ltd to investigate the direct impacts of sea-level rise on the harbourside and the southern city. While the report is considered to be a rough starting point in managing the issue, it calculates that a 0.1m rise in sea level will result in a 0.09m rise in groundwater. So, as sea level rises, groundwater will rise closer and closer to the surface. This will have significant repercussions in high rainfall events as a higher water table decreases the ability of water to drain off low-lying land, increasing the severity of flooding.

So, is the issue really that pressing? Insurance Council NZ Chief Executive Tim Grafton has recently stated that insurers will pay out $30 million after the flood in June. In Hilton’s opinion, based on these costs, the issue is “already pressing. The likelihood of that flood reoccurring or similar flood costing a similar or more amount of money could only increase as sea level rises. So, as it does, the risk will increase that we will have another flood of that magnitude.”

Fortunately for Dunedin, Beca’s report outlines a range of options to deal with the problem. The most probable option in the near future is to continue to drain and pump the water with large underground systems. While these systems in South Dunedin will have to be upgraded, Denmark has shown that it is an entirely plausible solution to deal with flooding. Denmark, at some points, sits five to seven metres below sea level and has successfully dealt with lowland flooding by pumping. They, too, will face increased flooding caused by raising seas, but have the mentality of continuing to pump even harder into the future. The report also recommends installing wells around the periphery of the flooded area to deal with increased flooding late into the century by further expelling floodwaters.

On top of these solutions, Hilton added the hard-to-sell option of retreat. That is, completely relocating the South Dunedin population. This, too, would be tricky. Where could you shift 10,000 people onto land that isn’t naturally hazardous or agriculturally productive? It would also be costly and socially problematic. Another potential option is to literally raise the land of South Dunedin, as has been done historically. Block by block, sections could be raised with rubble, dirt or clay from building sites and road works, which are expensive to dispose of in landfills. While it seems hard to imagine what seems to be a life-sized game of Lego, raising the land is a viable option that has been used overseas.

The biggest problem associated with managing the issue is, as usual, finances. Someone has to pay for whatever option will be carried out, and the DCC isn’t exactly balling at the moment.

The issue is environmentally, socially, economically and politically complex, presenting a whole range of uncertainties for the city to deal with. As we move through the century, we will no doubt begin to see increased cyclonic activity, rainfall and flooding that we can truly attribute to climate change. For the time being, the South Dunedin groundwater and flooding issue will continue to plague the city, and will only worsen as the sea rises in a warming climate. The scenario presents itself in a way that closely mirrors evolving worldwide urban attitudes to managing global warming: while reducing emissions remains as important as ever, we need to find ways to adapt to global warming in order to survive this changing world.