About two months ago, Critic published a story titled ‘A Seat at Our Table’ which shared the experiences of Māori students here at Otago University and the stigma surrounding alternative entry pathways. While the article and interviewees were met with plenty of support, there was no shortage of naive and insensitive questions and comments. The aim of the first article was to shed a light on the inequity, racism and scrutiny that Māori students face at university, especially within competitive programs. It sparked an important, much needed dialogue that must continue, especially in light of the recent news which has come out of Otago Medical School.

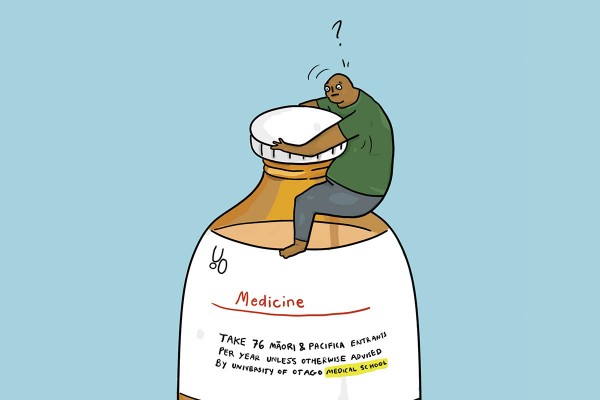

In case you haven’t heard, in recent weeks a proposal has been made to the Otago Medical School to cap the number of Māori and Pasifika places for entry into the professional health science courses, such as Medicine and Dentistry. Other alternative entry pathways, such as rural, refugee or low socio-economic could also be affected, but so far the reportage has focused on an alleged 56-person cap on Māori entrants and 20-person cap for Pasifika. From what we know of this discussion document, it has the real potential to conflict with Otago Uni’s ‘Mirror on Society Policy’ which aims to promote and facilitate academic equity for Māori and Pasifika students, as well as those from other under-represented groups, in the health sciences. This policy was introduced less than a decade ago, and so far has successfully achieved its aims to foster generations of health professionals which will, in time, balance the currently inequitable health sector. Policies like that at Otago Uni encourages students from minority groups to return to their communities and give back. Over time, this policy has managed to achieve some great results, such as a four-fold increase of Maori and Pasifika entries into medicine since 2010. Despite this, there remains severe disparity within the healthcare system.

But this proposal isn’t just concerning for current medical students and the future of our healthcare sector. It’s concerning because it reinforces the struggles, inequities and stereotypes which Māori and Pasifika students are faced with day in and day out. It demonstrates that the effects of colonisation are still alive and well, that our voices are still suppressed. It is yet another example of minority students having to try justify and validate their hard earned place within these professional programs. More frighteningly, this proposal, the media coverage and rhetoric which surrounds it justifies institutional racism and harbours toxic misconceptions about minority students and their place within university and the health care system. But in the wake of this proposal, has anyone asked, what do students think?

Isaac Smiler, the president of Toko, the Māori Medical Students Association says that while he has enjoyed his time at medical school, there are still certain misconceptions which surround student pathways. One of these misconceptions being that entry pathways, which generally have different terms for admission, produced less qualified healthcare workers. “It’s been a rhetoric which has been going around that I disagree with,” he explains. “Medical school is a beast of a program, all the exams and tests are calibrated to test if you are safe and competent. For people to say because you’re Māori, you’re not as good as everyone else, is rubbish.”

Alice Ihaka, who is currently a second year medical student, said her experience in med school has been positive so far. For the most part, “We’re all supportive of each other”, she says. For those who aren’t supportive, she said that part of the hostility is simply due to the misinterpretations of what the criteria actually is. “With logistics of grades, they aren’t letting people with a B in. We’re all pretty similar. Once you’re in, you sit the same exams as everyone else in medical school, so what does one year, or a two percent difference make?” However, these misconceptions and the hostility which surrounds them did get to Alice during her first year of Health Sci. “I noticed last year I did well, but not as well as I would like to do. That was because I felt incompetent with how people looked down on me or spoke to me,” she says. “I went to a shitty public school, I earned my place,” she said.

Not only this, but the media coverage of the entry pathways and the current proposal also add fuel to the fire. “It’s frightening based on what’s been going on in the media, you see people saying ‘if I see someone with a Māori last name, I’m going to think they’re less qualified’. If someone sees my last name, they will make that assumption about me. You never see people blaming rural pathways for taking up places. It really does show blatant racism.”

Hiraani Rieck, who is also a second year medical student, had almost the exact story. “I don’t know why people think that as a Māori, you’re less qualified even though we all do the same thing. There’s a threshold, they don’t just let anyone in. It’s still hard and you have to put in effort,” she says. “What ethnicity you are doesn’t affect what kind of doctor you are.” Hiraani further explains that many of these misconceptions are due to “a whole ignorance of history. No one thinks about the fact that all the effects of colonisation are still playing a part today.”

Isaac says that this shock proposal is contributing to a feeling of mistrust between students and the University. “There is a feeling of mistrust beginning to grow between Māori students and the University. There is work to strengthen and repair the relationship that has been damaged so far.” Alice and Hiraani agree. “Introducing a cap would really damage the pathways and support between students. I think it would discourage Māori students from going to uni and would create more toxicity within Health Sci,” Alice says. “It’s another hurdle you have to go through to prove yourself. If we put up more barriers … it just creates more separation, it takes away from recognising why people are there. I’m there because I’m a student of academic excellence, I’m Māori, and I’m dedicated to Māori health. I didn’t come in to be a statistic.”

“I always thought the medical school had a close relationship with Māori and Pasifika, but it makes me think there is still a sense of ignorance. It’s coming from people high up in the University, it baffles me we still are having these conversations,” says Hiraani. “Just from my experience, I even felt guilty applying under the Māori pathway because I felt I didn’t deserve it, but that was all the voices from other people getting to me. Everyone deserves a chance, if we did cap that pathway it would discourage Māori as they would have to compete with people who maybe had a better footing going into university.”

Aside from creating further challenges for Māori and Pasifika when it comes to medical school admissions, this proposal has the potential to worsen our already broken healthcare system and could deepen the already existing problems within Māori and Pasifika health. “We need Māori and Pasifika to go to their communities and help, but it’s just not happening right now. We are going to continue to see those shocking health statistics if we don’t get to the root of the problem,” says Hiraani.

Māori and Pasifika are underrepresented in the health sector – the statistics, according to Alice, is “not equitable or representative of Māori academic excellence. They don’t consider that the health workforce as of now is only 3.4 per cent Māori, there’s a major intergenerational gap that needs to be filled. We need to understand the process of colonisation, poor housing and lack of te reo has led to worse health outcomes. We need people who understand that, and that can connect to those things,” she says.

“Māori and Pasifika students are passionate about helping our people, that’s why we come to medical school,” says Isaac. He said that a significant cap could singlehandedly set back equity in the health workforce by decades.