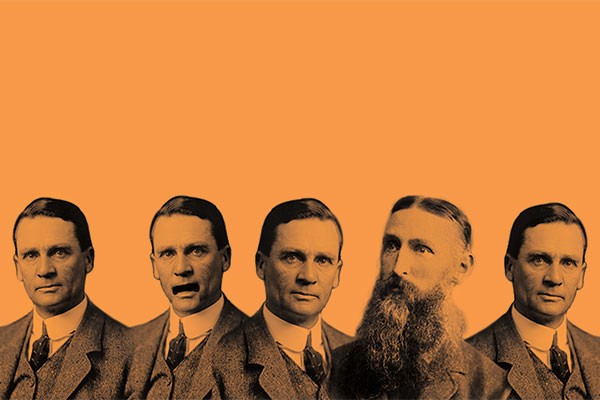

At the moment most students see the Dunedin City Council (DCC) as a body that does not serve their interests. And ultimately, that’s the point: it doesn’t. Only one fifth of the elected Councillors are women, none are under the age of thirty, and in photos the lack of diversity is confronting. Fortunately, we have the opportunity in October to change that.

Local body politicians are seen to be the poor cousins of their national counterparts. There is probably some truth to this: the big and most important policy levers are pulled by politicians in Wellington. Income tax, health services, education, and social welfare are all administered by central Government with oversight by our Parliament. Certainly when people think about “politics”, it is this to which they refer.

But this doesn’t mean that decisions made by local councils don’t matter. Most people interact more with local government than central government. On issues like housing affordability and transport, local government is able to pull a few levers of its own. These local matters may not set the direction of the country and be as sexy as the decisions made by central Government, but they are decisions which affect people directly each and every day. Young people and students are no exception.

In North Dunedin, there are a smorgasbord of services the DCC and Otago Regional Council provide that have an impact on students’ lifestyle. These range from bus services, cycle lanes, the frequency of rubbish and recycling collection, and local alcohol policy and liquor licensing. When it comes to the major decisions that affect students locally, they are driven by our local council.

We witnessed first hand how decisions by local council can fundamentally change student culture in Dunedin. In 2014 the DCC proposed a number of measures to curb student drinking and reduce the availability of alcohol in the city. The Council wanted no shots sold after 12am, a one-way door policy for bars and clubs after 1am, and a closing time of 3am for clubs across the city. They were decisions that set out to strike at the heart of a vibrant and bustling culture in North Dunedin. But more than that, they sought to restrict the legitimate choice of people to responsibly consume alcohol, and instead force people out from drinking socially in regulated and safe environments to their flats. At that time the Otago University Students’ Association (OUSA) successfully fought against the implementation of those proposals, but a council with students’ interests at heart should not have pursued them in the first place.

In an ongoing game of whack-a-mole, OUSA has continued to push back strongly against measures that students disagree with: a blanket liquor ban in 2012, proposals to introduce surveillance in North Dunedin in 2015, and an attempt to introduce another liquor ban in that same year. When one awful policy is defeated, another springs up to take its place. Council has been relentless. The risk with relying on OUSA to assume this role is that it may not always continue to be so steadfast in its opposition. What happens when elected student politicians lack the political clout to have those fights? Are students willing to have the very fundamentals of student life in North Dunedin stripped away?

That’s why it’s vital that students hold the people who are elected to public office to account. Dunedin City Councillors lack the political impetus to pursue student-friendly policies. The reason for that is simple – students aren’t enrolling to vote, and they’re not voting come election time. At the moment only 49 percent of eligible voters in Dunedin between the age of 18-25 are enrolled to vote in local body elections. This means that elected Councillors have little fear of electoral pushback if they implement unpopular decisions that affect young people. They know that students have no power currently to boot them out at the next election. Perhaps this is a cynical view of politics, but it reflects the realities of our democracy. While elected Councillors ought to govern for the whole community, they are too often beholden to the groups and constituencies that get them elected to office. Even more so when those groups are donating to their political campaigns. Unfortunately, this approach has meant that students, who are a huge chunk of the Dunedin community, are completely shut out of local politics.

In all of this, it’s older folk that are benefiting. In Dunedin, older people religiously vote at local body elections, and the Council panders to their interests accordingly. Remember Carol of the now infamous piece aired on Sunday last year? Her complaints typify the thoughts and feelings of a large body of people in Dunedin. They see students as destructive alcoholics that contribute little to the city and ruin their quality of life. Of course this isn’t true. The University and its students make a massive social and economic contribution to Dunedin. The problem is that people like Carol can be relied upon to vote—89 percent of people over the age of 70 vote in local body elections. This makes proposals like liquor bans and introducing surveillance appealing to political candidates looking to get elected. And get elected they do.

Part of the problem is that students feel that they should abstain from voting in elections here in Dunedin. Research conducted within the University of Otago Politics Department shows that students think that they have no right to vote given they are only in Dunedin for three years, and that they should only vote in their hometowns. The truth is that students are as big a part of the community as anybody else–they are indirect ratepayers, support local business and utilise local infrastructure. Therefore students have a legitimate claim that as users of those services they should be able to vote in local body elections. For students to act as a counterweight to the majority of Dunedin voters, and to successfully advance their interests at a local government level, they need to enrol to vote at their Dunedin address and cast votes during election time. Participation in local democracy should play an important part in community building—all people, regardless of where they fit within the community, should be encouraged to participate and decide on who represents them.

It is also clear that the lack of hype surrounding local body elections contributes to low student turnout. Students simply aren’t aware that the process is happening. Unlike general elections in New Zealand where there is extensive media coverage, TV debates, and prominent party political advertising, local body elections are a comparatively low-key affair. The DCC and Electoral Commission (the statutory body responsible for enrolling voters) should make every attempt to ramp up the prominence of local elections. This ought to include working with organisations, like OUSA, who have a better knowledge of their communities and people they represent. That’s why it’s particularly surprising that the DCC has refused to establish a polling booth on the University of Otago campus this year for the local body elections. Increasing the visibility of the process and promoting the act of voting would only serve to engage young people in the very process they have been alienated from.

Some of the concerns about student voting appear to be driven by an idea that students are a homogenous voting bloc. We don’t all vote for the same political parties, we aren’t all “left wing”, and in turn we are unlikely to vote for the same local body candidates. The student population is diverse, and it’s these differences that make North Dunedin a unique and more exciting place to live. However, the common experience we have in Dunedin does mean that a lot of us share similar concerns in respect to certain issues. The quality of housing stock, a desire for more frequent rubbish collection to serve the needs of the student quarter, and defending our ability to enjoy a beer when walking to a friend’s flat are just some of our collective concerns.

By engaging in local elections, and being voters, candidates are more likely to campaign on issues that matter to students and govern on their behalf. This can be contrasted with the approach of current Councillors who have a dismissive and antagonistic attitude towards the student population. In an interview in 2015, Dunedin City Councillor Lee Vandervis described students as “troublesome little snots”, and his colleague David Benson-Pope likened some student streets to “a bloody slum”. The language used seeks to tar all students with the same brush, and it’s accepted because students aren’t holding them to account at the ballot box.

There is no doubt that the DCC and the wider community are cautious about increased student turnout in local elections. Make no mistake: if students voted en masse, it would have an overwhelming and decisive impact on the election results. It would be enough to elect councillors. Certainly it would send a clear message that students are serious about participating in the electoral process and casting votes to shape Dunedin’s future. This isn’t important only for students living here today, but also for the next generation of students, and the generation after that. What if, instead of a relentless push to clamp down on the student quarter, the Dunedin City Council focussed on the bigger picture and the issues that matter? Creating a city that attracts and retains young people, has a thriving young professional culture, is sustainable and responsive to the issues of climate change, and creates opportunities for everyone.

Our democracy, at both a national and local level relies on people ‘turning up’ and voting for the representatives they think will best serve them and advance their issues. In Dunedin, we have a situation where students are being left out of this process, either by deliberate attempts to not engage with them, or using them as scapegoats to advance personal political agendas. It’s clear that the issues decided by the Dunedin City Council affect everybody who lives here. We all use roads and footpaths, consume water, have our rubbish collected, and directly or indirectly pay tax to the local government. Enrolling, and voting in local body elections is important because it decides the future of our city and the provision of services. More than that though, it shows that students will no longer accept being ignored and shut out of process which would only be enriched by their participation.