Religion: Explained

Somewhat less impressively, three million Muslims undertake the annual Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca. These massive gatherings of religious adherents are neither rare nor distinctly modern phenomena. Both the Kumbh Mela and the Hajj, to stick to our examples, have been celebrated for hundreds of years, albeit at smaller scales. These great pilgrimages come at proportionally great individual and institutional cost and risk. Even with the availability of commercial travel options, pilgrimages are heavily energy- and resource-intensive endeavours. Furthermore, they pose enormous health risks, especially from bacterial and viral infection. Indeed, pilgrims may even get trampled to death by other pilgrims! Speaking of the costs associated with religion, most organised religions expect financial contributions from their adherents. For example, most Christian denominations famously expect congregants to tithe ten percent of their income to the church. On top of that, religious merchandising has kept religious organisations in business for millennia. First-century Jewish money-changing, medieval Roman Catholic sales of Indulgences, and the modern multibillion-U.S.-dollar-per-annum Christian music industry come readily to mind. Besides these health and resource costs, religion also incurs a significant reproductive cost, making it something of an evolutionary conundrum. Many major religious traditions – including Roman Catholicism, Buddhism, and Hinduism – include castes of celibate clerics or students. Furthermore, lay people are often required to be temporarily abstinent for ceremonial purposes. Indeed, most major religious traditions consider sexual intercourse before marriage to

be sinful.

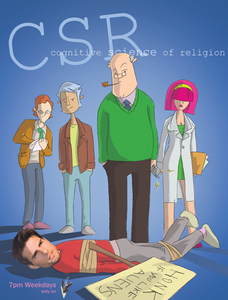

Despite the costs associated with religion, religiosity is a ubiquitous feature of human society. Perhaps more remarkably, religion has also withstood acute antagonism from political regimes, such as in Russia and China; such political attempts to eliminate religion have been notoriously unsuccessful. The demise of religion has been prophesied since the Enlightenment, and yet religion shows no signs of waning at a global level. If history is any guide, it appears that the contemporary attempts to extinguish religion, associated with the New Atheists, are doomed to failure. But why should this be? Why are human beings so incorrigibly religious? Why is religion so pervasive, given the internally-incurred and externally-imposed costs associated with it? Everyone – lay people and scholars alike – seems to have pet theories about this; the history of ideas is replete with attempted explanations of religion. But it’s only in the past 15 years or so that promising theoretical and empirical research has been conducted; now, the “cognitive science of religion” (CSR) is a burgeoning inter-disciplinary field, mostly involving psychologists, anthropologists, biologists, religious studies scholars, and philosophers.

All this talk of the oddness of religion raises the question of what we mean by ‘religion’. Like most categories in the natural and social sciences (e.g., gender, ethnicity, species, and disease), religion is fuzzy: it is incredibly difficult, if not impossible, to list a set of necessary and sufficient conditions for something to count as a religion. But this inability to exhaustively define religion is not, as some think, devastating to the scientific enterprise of explaining religion. As in other fields, all we need is a working definition that helps us to specify and limit our area of inquiry, regardless of whether our definition includes all and only those things that everyone agrees is a religion. While CSR is characterised by its diverse approaches, many researchers – myself included – are interested in the belief in supernatural agents (or ‘gods’, for short), and the phenomena (such as other beliefs, social structures, rituals) associated with those beliefs.

This perspective elicits the predictable objection that lots of things we want to call religion don’t involve gods. Theravada Buddhism is the oft-cited example here. In response, researchers point out that while there are religious philosophies (or theologies) that do not involve gods in any recognisable sense, adherents of these philosophies invariably believe in supernatural agents. Theravada Buddhism might officially be atheistic, but Theravada Buddhists believe in multiple gods, and we are primarily interested in people, not texts. Besides, even if this god-centric approach fails to encompass absolutely all of what we might call religion, it certainly covers most of it. Most people, in most times and places, have believed and still believe in supernatural agents – in omnipotent beings, tribal deities, angels, demons, djinns, souls, and spirits of various kinds; all counterintuitive and elusive beings, rarely amenable to normal detection, sensation, and perception – and these materially and reproductively costly beliefs are our domain of research interest.

The naturalness of religion

Despite the publication of such books as Religion Explained, How Religion Works, and Why Would Anyone Believe in God?, the CSR research programme is far from over. There are still fundamental disagreements among scholars over, for example, whether religion is an evolutionary adaptation or a by-product of evolutionary adaptations. Some scholars even question the importance of evolutionary considerations in theories of religion! However, the last decade or so of inter-disciplinary, piecemeal, and theoretically and methodologically pluralistic research has led to some valuable insights towards explaining religion. Different researchers are bound to diverge somewhat over what these key insights of the field are, but in my estimation three inter-related ideas stand out: hypersensitive agency detection, minimal counterintuitiveness, and inferential richness.

We humans are promiscuous anthropomorphisers. We see faces in clouds, and hear voices in the wind; we believe that our pets have rich mental and emotional lives and behave as though our computers and vending machines are similarly sentient (even accusing them of malice and incompetence). We are, in the jargon, hypersensitive detectors of agents. Hypersensitive because we detect non-existent agents more than we miss present ones. This hypersensitivity, evolutionary psychologists argue, was an adaptation that fit a world full of deadly predators: it’s better to mistake a boulder for a bear, than a bear for a boulder. After all, the former error comes at the cost of some energy spent running away unnecessarily, while the latter comes at the cost of death by mauling and mastication. So, we see agents (i.e., person-like beings) everywhere, and that’s why we see supernatural agents everywhere. Put another way, the same tendency that leads us to see art and artifacts as products of a human agent’s beliefs and desires (as opposed to, say, the mindless splashing-on of paint by a machine) lead us also to see (rightly or wrongly) crop circles, bacterial flagella, and rainbows as products of supernatural agents’ beliefs and desires.

Individual people hearing voices in the wind, does not a religion make; at least, not the kind of religion that interests us. Time and time again, stories about gods have spread to dozens, hundreds, thousands, and even millions of people, but what makes these stories so memorable and transmissible? For starters, these stories are interesting (and we will look closer at why they’re interesting in a moment), without being bizarre. That is, they are minimally counterintuitive. Cross-cultural anthropological and psychological research strongly suggests that all human beings share some basic, unreflective, intuitive beliefs. We believe, for example, that two objects cannot occupy the same space. We might not be able to express this belief propositionally, but people from all cultures are surprised at the sight of a solid object passing right through another solid object. We believe, for another example, that animals reproduce offspring like themselves. Once again, we might not be able to express this belief propositionally, but people from all cultures are surprised to find puppies hatching out of chicken eggs. According to cognitive anthropologists then, we have automatic expectations (or folk theories) about different categories of things, and things that violate these expectations are counterintuitive. Now, something can be more or less counterintuitive. A chicken that lays eggs with puppies in them, but is otherwise normal, violates a single categorical expectation; a chicken that can walk through walls and also happens to lay eggs with puppies in them (but is otherwise normal) violates two, and is thus more counterintuitive. Taking it a few steps further, a chicken that is made of metal, walks through walls, speaks fluent Dutch, grants wishes, turns into a werewolf during full moons, and lays eggs with puppies in them (but is otherwise normal) violates many expectations, and is very counterintuitive indeed. Perhaps unsurprisingly, even if such maximally counterintuitive beings were just as plausible, they are far less memorable (and therefore transmissible, for we have to be able to remember a story in order to retell it) than so-called minimally or optimally counterintuitive beings, which only violate a few expectations. More interestingly, recent research suggests that minimally counterintuitive concepts are also more memorable than simply intuitive concepts. This might seem obvious, but the consensus from the research used to be that familiarity conferred massive memory advantages, and since intuitive concepts are more familiar than minimally counterintuitive ones, they should be more memorable. But what has this got to do with gods? Well, it turns out that gods – or at least, successful gods – tend to be minimally counterintuitive agents. Spirits, for example, are invisible persons that pass through walls; this violates our expectations of persons qua physical objects. (As an aside, invisibility is a common attribute of gods, perhaps because the existence of invisible gods is much harder to disconfirm. Usually, we pick up on our false positives in agency detection when we, for example, take a closer look and realise that the large brown object is a boulder, rather than a bear. In the case of invisible gods, such straightforward disconfirmations are unavailable.) Some gods, for another example, are immortal; this too violates our expectations of persons qua living things. So, stories about gods are well-remembered and transmitted because they involve minimally counterintuitive agents.

I promised earlier to examine the claim that gods are interesting. It turns out that the interestingness (or, technically, inferential richness) of god concepts not only make them more memorable for transmission, but also make them more believable. Now, consider that many conceivable minimally counterintuitive agents do not occur in religious traditions. Sentient, talking trees occur in religious mythologies, but rarely do we get silent, inanimate humans (except insofar as they are made thus by angry gods). Disinterested deities have been speculated about in religious philosophies and systematic theologies (e.g., Enlightenment-style Deism), but have never really caught on. And there’s never been a religion based around a god who lives in an alternate reality, who has never had and never will have anything to do with anything in our own world. Irrelevant beings don’t become gods; only relevantly interesting ones do. Now, a concept is relevantly interesting if it can be invoked usefully in many different domains, and especially if these domains are are subjectively and emotionally significant to us (e.g., morality, mortality, and sexuality). The concept of an invisible person (e.g., an ancestral spirit), for example, can easily be invoked as a moral policing agent. The concept of an all-powerful god or even a god with special powers in limited domains, on the other hand, can easily be invoked to explain natural phenomena. So, we readily believe in gods because we find relevantly interesting concepts plausible, and god concepts are relevantly interesting concepts.

The (un)reasonableness of religion?

The cognitive science of religion is the study of a specific, albeit complex, set of human psychological facts: religious beliefs and behaviours. In other words, we study human persons, not divine ones; we study people’s concepts of gods, not the gods themselves. As such, the question of whether or not any given god exists goes beyond our field. However, our attempts to discover naturalistic explanations of religion – that is, ones that do not invoke divine intervention – look suspiciously like attempts to explain religion away. Are not such accounts always in direct competition and contradiction with the account of religious belief in which Yahweh speaks directly to Moses on Sinai or the one in which Allah speaks through the angel Jibreel to Muhammad in Hira? Furthermore, does the particular account I sketched out, which involves a hypersensitive tendency to detect agents, imply that the belief in gods are products of aforementioned false positives? Much like everything else in the field, the answers to these questions are still heavily debated. However, there are a few pitfalls we should avoid. (Needless to say, not everyone thinks they are pitfalls, but never mind them.)

First, we should be careful not to commit the genetic fallacy: the error of concluding that a belief is false because of some feature of its origin. Here’s an everyday example: my intuitions tell me the All Blacks will win the next match they play; my intuitions are notoriously inaccurate, especially when it comes to sport; therefore, it is not the case that the All Blacks will win the next match they play (i.e., they will lose or draw it). It should be obvious that the way I arrived at the belief that the All Blacks will win the next match they play has no bearing on whether or not they will in fact do so. Of course, this is not to say that the origin of a belief has no bearing on its rationality or reasonableness, which leads us to our second pitfall.

We should be careful not to confuse the context of discovery and the context of justification. The context of discovery concerns how someone came to believe something, in the origin of the belief as above. The context of justification concerns how someone comes to prove or defend or otherwise justify the belief. Here’s an example from the history of science: August Kekulé famously claimed to have discovered the chemical structure of benzene after a daydream of Ouruboros, a snake biting its own tail. Upon receiving this revelation, Kekulé marshalled arguments and evidence for his new theory. Now, just because the original idea came as a result of a dream (which, we’ll assume, is an unreliable way of discovering chemical structures) doesn’t render Kekulé’s (and our) belief that benzene has a ring structure irrational, given that we have persuasive arguments and evidence for this belief. Whether a belief is reasonable, then, depends on the context of justification, not the context of discovery. So, religious believers might well be reasonable in holding their religious beliefs, despite the fact they originally began holding them for non-rational reasons.

Thirdly, an error in the opposite direction: the compatibility of religious beliefs with naturalistic explanations of religion guarantees neither their truth, nor their reasonableness. So far, the religious reader might have taken some comfort from my claim that explanations of religion do not necessarily render religious claims false and/or unreasonable. And so they should, but they should not remain complacent. CSR does raise challenges for religious belief. First, if a naturalistic account of religious belief (or the origin of religion or the origin of a specific religion) is adequate, then we no longer need to invoke God (or gods, etc.) in this domain. So, if the religious believer still wants to maintain that their religious beliefs (or religious tradition) were inspired by God, they have to provide arguments and evidence for their case. Failing that, Ockham’s Razor leads us to prefer the simple, naturalistic explanation sans redundant deities. Second, if our tendency to detect agents is indeed hypersensitive, then we had better not naïvely trust the beliefs generated by this unreliable process. Indeed, we want to be careful, especially if the agent we’re detecting is quite unlike other agents with which we’re familiar. And gods, as I have said earlier, are precisely unfamiliar, counterintuitive agents.

The cognitive science of religion is exciting, not just because its subject matter has been shrouded in taboo for centuries, but also because it is still in its infancy and there’s still so much to discover. And as with many exciting endeavours, it is also challenging, not just because empirical research on people’s cherished beliefs is difficult (though it is!), but also because we are constantly faced with philosophical and theological issues too. In light of this, inter-disciplinary co-operation and scientific humility is necessary; it is far too easy to abuse the science for the sake of militant atheism or religious fundamentalism, and far too difficult to express a nuanced, objective view on the repercussions CSR might have for religious belief. Wish me good luck; I’m going to need it.

Jonathan Jong is a PhD. candidate in the Dept. of Psychology and Dept. of Philosophy. He is investigating various factors that influence religious belief, and how theories of religion affect the rationality of religious belief.