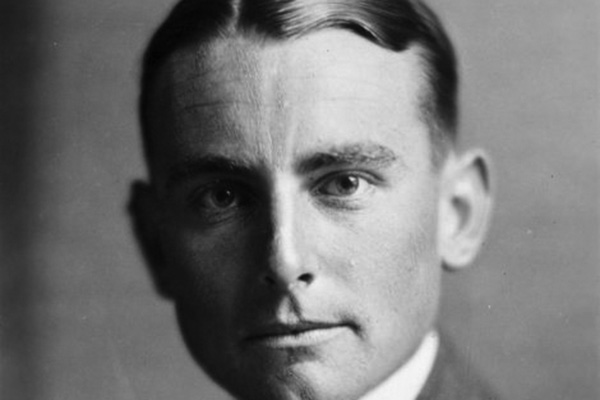

Profile: Sir Geoffrey Cox (1910-2008)

Critic Editor 1930

His days were crammed with intrigue and excitement, and early in his career, he was often thrust into witnessing the worst regimes of the twentieth century. But Cox never lost sight of a journalistic integrity that helped to rescue British independent television news from the exploitative yellow journalism that has come to characterise much of the country’s print-media. So how did a boy born in Palmerston North come to be a key figure in British news journalism for over twenty years?

Cox didn’t speak much of his stint at Otago University, nor indeed his editorship of Critic. In Cox’s day there were three editors: one from Knox, one from Selwyn, and in an early if patronising example of equal opportunity employment, a “Lady Editor.” Cox was the Selwyn Editor. The Critic that Cox oversaw is almost unrecognisable to the modern reader, but similar themes arose now and again. In an April 1930 issue, the self-anointed “Knox College Misogynist’s Club” complained of well-off girls refusing to pay for their own dance tickets. Letters to the editor openly wept of the sexual neglect thrust upon some fresher males, albeit in a euphemistic tone. Articles did not reflect the economic mayhem of the period, and were largely farcical in tone. The most striking difference is a shift from advertisements for pipe tobacco and Scotch whisky in Cox’s Critic, to the enormous anti-drug PSAs that dominate much of modern student media today.

A decisive moment in Cox’s life came when he was granted one of New Zealand’s two Rhodes Scholarships, hand-picked by the Governor General Viscount Bledisloe, in 1931. In a stroke of luck, he won the trust of Bledisloe through his mutual interest in pig-breeding. Before arriving at Oxford in 1932, and observing its stifling class system, Cox travelled to the Soviet Union to assess the credibility of Marxism. He visited during a nadir of Soviet existence, and saw glimpses of a year-long famine that claimed roughly six million lives. Russia was not hurting as economically as the rest of the world, but its people were starving. It was in this environment of two deeply dysfunctional opposing ideologies that the embers of fascism began to spark.

On the very date that Hitler won election, 31 July 1932, Cox arrived for the first of his two trips to interwar Berlin. He stumbled into the uncertain environment of a fledgling Weimar Republic, amid various political ideologies vying for power. The streets were draped with an artist’s palette of party flags; red, white and black for the monarchists; the hammer and sickle for the communists; and the black swastika for the Nazi Party. Cox observed that Germany was a country of remarkable “freshness and freedom,” with bookstores flanked with H.R. Knickerbocker’s Deutschland: so oder so? [Germany: either way?]. Uncertainty about Germany’s submission to either left or right was still yet to give way to the collective hysteria of Nazism.

When Cox returned to Germany in the winter of 1934, the Nazi party had extended its grip over every aspect of German life. This was the year Hitler granted himself total autocracy by consolidating the roles of Chancellor and President under der Führer. Political prisoners were already commonplace, and Cox befriended the wife of an imprisoned communist leader.

Shortly after dining with her in uptown Berlin, Cox refused to Heil Hitler when prompted by a large group of stormtroopers on a street corner. He was rewarded with a blow to the back of the head and only regained consciousness minutes later. Shortly after, the pharmacist who treated Cox instructed him to “wait till [Oswald] Mosley is in power in England, and you too will appreciate what discipline and soldierliness really are.” The Nazi soldiers’ abusive behaviour may be no surprise to the modern reader, but helped set in stone Cox’s opposition to the looming spectre of fascism. Cox’s further experiences in Germany testified to the unprecedented changes taking place in a nascent Third Reich.

Crucially, Cox was present at the 1934 Nuremberg Rally, best known as the setting of Leni Riefenstahl’s infamous documentary Triumph of the Will. With an estimated three hundred thousand attendees, Cox was particularly lucky to secure the Nuremberg equivalent of an Opera Box: the window of an acquaintance’s bookshop.

With the bookseller’s binoculars, Cox studied Hitler and his deputies for four full hours. Cox was impressed by Hitler’s stamina, standing upright for the entirety of the Rally. Frenzied housewives dabbed their swollen eyes with handkerchiefs, while tens of thousands of Hitler Youth watched their namesake in wonder. Cox later commented on Hitler’s appearance, noting that his face was a “strange blend of ordinariness and strength.” Fluent in German, Cox was nevertheless immune to Hitler’s abhorrent charisma; his 90-minute speech was not made for foreign consumption. Hitler boasted that he now embodied Germany and that supreme power was now held by the Nazi Party.

Cox’s initial motivation for returning to Germany may seem borderline suicidal at first glance. While at Oxford, Cox had felt deprived of the physical exercise he had enjoyed as a farm hand in New Zealand. Confronted by a German scholar for his anti-Nazi sentiments, Cox readily accepted his invitation to attend a labour camp in Germany. The camp was designed to draw, as Cox described, “puny and undernourished” young men from Germany’s metropolises.

One might assume that after getting bashed in the head by a Nazi soldier and witnessing the terrifying spectacle of the Nuremberg Rally, Cox would be reluctant to go back. Daringly, though, he travelled to rural Hanover as an Arbeitsmänner [Labour Service member]. Fortunately, the camp was a far cry from the atrocious death camps of the war years, and indeed Cox found the work to be “not very hard.” In one memorable anecdote, Cox recounted how he taught his fellow Arbeitsmänner a Maori haka. Cox later pondered whether any of his long-lost comrades “as soldiers in Crete or the Western Desert heard the haka roared out in reality, as the Maori Battalion of the 2nd NZ Division came towards them.”

Perhaps the biggest break of Cox’s life came through his reportage of the Spanish Civil War whilst working as a junior reporter at the News Chronicle. Unlike a great number of his colleagues, Cox elected to stay in Madrid just as Franco’s forces began to threaten the city. Faced with probable imprisonment if the city fell to fascism, Cox took a gamble that paid off. The Republicans outfought the favoured Nationalists, and Cox was one of only three British journalists to enjoy an inside scoop on the 1936 Battle of Madrid.

Upon his return to London, Cox did not graduate from chasing fire engines and ambulances, but earnt a reputation as a dedicated and objective reporter. It was with these experiences in Madrid that he wrote his first book, Defence of Madrid, a book still considered an authoritative account of the Spanish Civil War.

When war arrived, Cox chose to serve under the jurisdiction of his home country. As a chief intelligence advisor to General Bernard Freyberg and a member of the Pacific War Council, Cox sat at the same table as Churchill and Roosevelt. Cox was in Crete in 1941, where New Zealand troops fought and lost a battle with German invaders. He later reflected that “My first reaction was, ‘I might be dead by tonight, but by God, I’ve seen the first airborne invasion in history.’”

In 1956 Cox won the job as Chief Executive of ITN, the United Kingdom’s first independent television news company. In its infancy, ITN had suffered from major budget cuts that prompted Cox’s predecessor to resign less than a year into his role. Much of the station’s talent was moving to the BBC, leaving the company with an uncertain future. But Cox helped ITN secure a reputation for removing spin and making their reports digestible for even the most unenlightened viewer.

In 1967, as Cox’s parting gift a year before he resigned, ITV’s News at Ten was established. A familiar fixture for many Britons, the show was the first news broadcast with two readers, a tactic initially employed so that one reporter could receive breaking news as the camera focussed on the other. The show was significantly longer than its predecessors, allowing a deeper reportage that is seldom seen on television today. When News at Ten was axed for nine years in 1999, Cox wrote in The Times that its dismissal would “strike a blow at the functioning of democracy in Britain.” He lived long enough to see the station he helped establish descend into reality TV, but also saw News at Ten’s renewal in 2008.

Cox lived a life that would make Tintin jealous, packed with adventure, and witnessing some of the crucial political regimes of the twentieth century. He has been largely overlooked in his home country, partly because he spent so much of his life trying to strike a balance between being a Briton and New Zealander. As one of the great New Zealanders of the twentieth century, Cox is likely the only Critic editor knighted for services to journalism.