Full disclosure: I’m white. I don’t have a particular axe to grind, and I like to think that I’m not racist. I also like to think that I, like many other New Zealanders from all kinds of backgrounds, am willing to look at all the facts and decide what to think without taking racial prejudice into account

One Maori? Or many Maori?

Firstly, we should remember that Maori are only a “race”, but a variety of individual cultures. People who identify as Maori but live at different ends of New Zealand have very important cultural differences. By classifying Maori people as one homogenous group without taking into account their differences, you’re losing before you even begin. The fact is the people, customs, and histories of Maori are so vast and varied that they can’t can be chucked into one big pile. But I’m getting a bit off topic. Why does the Treaty of Waitangi matter to you (whoever you are) and me? Kara Dentice, an Otago student and member of Te Roopu (The Maori Students’ Association), thinks the Treaty is just as important to Maori as it is to non-Maori. “Even though the Treaty might affect them in different ways, there needs to be a greater understanding of the Treaty by everyone.” He thinks that cultural discrimination in New Zealand is seen as a bit of a sensitive topic, because no one wants to be called a racist, but that a bicultural New Zealand should be something so widely accepted that it isn’t even talked about. “Because we [would] live in a world which is built on the desires and hopes of the Treaty… a truly equal New Zealand, where Maori values and tikanga (cultural practices) are imbued at the same level as their Pakeha equivalents.”

But I’m getting a bit off topic. Why does the Treaty of Waitangi matter to you (whoever you are) and me? Kara Dentice, an Otago student and member of Te Roopu (The Maori Students’ Association), thinks the Treaty is just as important to Maori as it is to non-Maori. “Even though the Treaty might affect them in different ways, there needs to be a greater understanding of the Treaty by everyone.” He thinks that cultural discrimination in New Zealand is seen as a bit of a sensitive topic, because no one wants to be called a racist, but that a bicultural New Zealand should be something so widely accepted that it isn’t even talked about. “Because we [would] live in a world which is built on the desires and hopes of the Treaty… a truly equal New Zealand, where Maori values and tikanga (cultural practices) are imbued at the same level as their Pakeha equivalents.”

Tihema Nicol, another student I talked to at Te Roopu, also thinks it’s important that we remember that the ideas of giving in the Treaty are reciprocal and it’s not all about taking land, money, or whatever else. “I think there’s a misconception in normal society that Maori are just taking… it’s important to understand that Maori are not the sole beneficiaries of the signing of the Treaty. A lot of people see Maori as getting Treaty claims, getting their land back, getting multi-million dollar deals with the government, and yet they don’t see what’s happening at a local level where… [things have] been put back into the community not just for Maori, but for better wellbeing of the community as a whole.” Kara agrees. “Maori are the most giving people in this country. Even people who have nothing will give everything they have.” When the Treaty was signed, Maori at Waitangi gave their food to the European settlers, even if it meant going without themselves.

Treatygate?

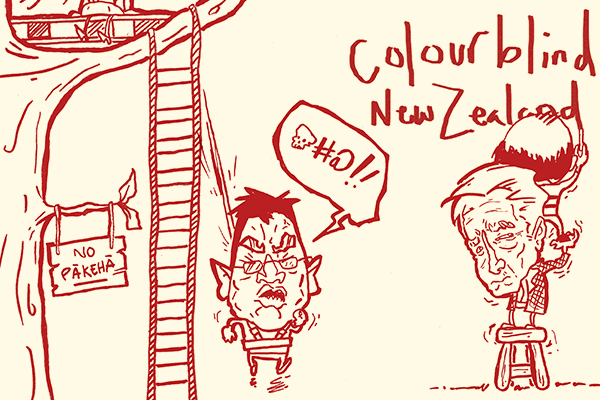

But what about this Treatygate thing? For those of you who haven’t been reading the Critic lately (naughty!), there’s this guy John Ansell who is calling for New Zealand to become a “colourblind state”, with no race-based prejudice or recognition of race in general. This means no Treaty, no seats in Parliament based on race, and a completely different New Zealand. It could also mean some pretty bad things for Maori people. Dr Paerau Warbrick is a barrister and lecturer here at Otago. He believes that “the media needs to ignore [John Ansell] as an extremist”, but the same applies to Margaret Mutu and Hone Harawira, who are “extremists on the other side”. “John Ansell has made a lot of money out of pitting New Zealanders against New Zealanders. Why should we, as a nation, give him the time of day?” Warbrick also argues that the Treatygate idea isn’t pragmatic, because people do things and understand things differently. “Let’s take race out of the equation. Do you really think that the people of Dunedin and the people of Hamilton are the same? There are different cultural and historical settings for the two cities.” In essence, the same could be said for all the different groups of people in New Zealand.

Dr Paerau Warbrick is a barrister and lecturer here at Otago. He believes that “the media needs to ignore [John Ansell] as an extremist”, but the same applies to Margaret Mutu and Hone Harawira, who are “extremists on the other side”. “John Ansell has made a lot of money out of pitting New Zealanders against New Zealanders. Why should we, as a nation, give him the time of day?” Warbrick also argues that the Treatygate idea isn’t pragmatic, because people do things and understand things differently. “Let’s take race out of the equation. Do you really think that the people of Dunedin and the people of Hamilton are the same? There are different cultural and historical settings for the two cities.” In essence, the same could be said for all the different groups of people in New Zealand.

The Maori students at Te Roopu agree. “It’s perspective without understanding,” says Kara. “I don’t think we have come to a time in New Zealand where we can say ‘We don’t need Maori seats… in Parliament, on the council, we don’t need to recognise Maori as a special culture of New Zealand,’ because if we do that, what’s going to happen to Maori? By virtue of [removing Maori seats from Parliament], we are removing the Maori voice.” And by removing the voice, we’re removing particular tikanga and customs from these institutions as well.

But David Round, a law lecturer at the University of Canterbury, has a different perspective. We already know what John Ansell is campaigning for – a society free from racial bias – but Round has a slightly less inflammatory approach. He says the most important thing is “what the Treaty actually says… simply that the Queen is sovereign, Maori are her subjects like everyone else, with the same rights as everyone else, including the enjoyment of their property. That’s it. No special privileges, no ‘partnership’ with the Crown, just equality of citizenship.” And here’s where the debate REALLY kicks off: what does “equality” mean?

Equal?

Lisa Pohatu, President of Te Roopu Maori, says that wanting equality versus equity is the main difference between the sides of this debate. Kara agrees: “The Treaty of Waitangi is about ensuring that we live in a New Zealand where there is a partnership between two different cultures, and an equal society.” Kara says that this is not an issue of race, but of equality. He thinks it’s important to ensure that “Maori values, cultures and views are upheld, because the minute we take away what might be imbued to be special rights, the dominant hegemonic group (in this case, Pakeha) sort of overtakes.” In 2005, David Round quoted Metiria Turei as saying that “Maori want two things. They want independence, and they want more funding.” This contradiction certainly doesn’t help the situation. So they want to be given money, so long as they can be independent with it? Who in their right mind would give someone funding, then let them do exactly what they want with it?

In 2005, David Round quoted Metiria Turei as saying that “Maori want two things. They want independence, and they want more funding.” This contradiction certainly doesn’t help the situation. So they want to be given money, so long as they can be independent with it? Who in their right mind would give someone funding, then let them do exactly what they want with it?

The problem here is that people have different perspectives, and are arguing for different things because they see words like equity and equality differently. To Maori, it’s about maintaining their culture, upholding their values, and having a functional bicultural society. Kara says this means “recognising there’s more than one way to do something. There is a Maori approach to everything and let’s see what that brings, even if you’re not Maori. There is a Maori way to do everything as there is a Pakeha way. Or let’s combine the two without the loss of one or the other.” He believes that in New Zealand society there is a silo effect, where “we gotta do this, this, oh and we gotta do the Maori stuff as well”, instead of integrating Maori culture with everything else.

But there’s always a flipside to the coin. There’s a common view in modern society, especially among the older generation, that the Treaty is now just a tool for the Maori people to take land and claim rights. You can see how this happened – many European families migrated to New Zealand, bought land off the Crown and worked it for generations, only to have it taken away from them. Sure, it technically wasn’t theirs in the first place, but you can understand how the sentiment arose. And you can understand where people like David Round and John Ansell get their ideas from.

New Zealanders seem to have an opinion on everything. whether it’s race relations, gay marriage, or raising the drinking age. But it’s important to understand how the things you’re talking about are affecting you. Everyone knows a little bit about the Treaty (signed on February 6, right?), but a lot of us do not realise just how much it underscores all aspects of New Zealand society and government. Were it not for the Treaty, European settlers might have taken New Zealand by force (well, more force). But the Maori people decided to share; they decided to give the settlers somewhere to live in return for various things and a reciprocal relationship where everyone does a little giving and a little taking. Unfortunately, it didn’t quite turn out that way. So why shouldn’t people who had their land taken from them have rights to it? And why shouldn’t the native culture of New Zealand be upheld? There’s one thing people seem to forget: New Zealand may be a society full of heaps of different people, but it’s the only place in the world where Maori are the native people. So if they lose the right to their own culture, what do they have left?