Ah, the pill. That tiny, circular tab that’s readily handed out to fix a myriad of issues, whether that be mental health, preventing periods, curing acne or, you know, maybe even as a contraceptive. Since its release in the 1960s, the oral contraceptive pill has been treated as a miracle drug, not only allowing women and AFAB (assigned female at birth) people more freedom than ever before, but also as a tool to fix other uterus-related issues.

But the pill is not always as cut and dry as it may appear, coming with a range of side effects that can have devastating impacts for some — especially when combined with pre-existing health issues. So, is the pill really the best solution for these issues that modern medicine has to offer? Are we treating this medication with enough caution for something prescribed so willingly? Critic Te Ārohi investigates.

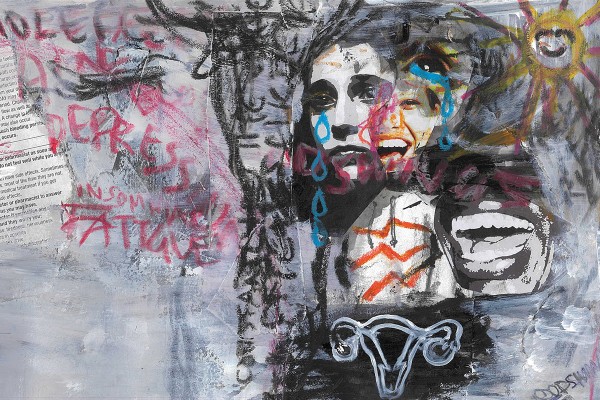

The pill carries some serious risks and potential side effects. As the veritable blanket of paper that comes inside the medication’s box warns, side effects can include: acne, fatigue, insomnia, depression, bloating, and mood swings. Students Critic Te Ārohi spoke to shared their struggles with the emotional and physical side effects that they attributed to taking the pill.

Everyone knows periods can be a bitch, but some have it much worse than others. The pill is often prescribed to alleviate symptoms. Second-year Jess initially went on birth control at age fourteen to treat severe periods that were causing her anaemia. But it wasn’t a quick fix. Since then, Jess has tried multiple different kinds of the pill in an attempt to regulate her flow. While trialling these many variants, her periods became incredibly erratic. “I could go four months of just straight bleeding, two days no bleeding, and then six weeks of more bleeding. There was no clear cycle.”

When a patient is switched from pill to pill in an attempt to solve a physical health issue, as in Jess’s case, hormonal shifts in the body can cause even more side effects. “I had crazy side effects from just bouncing from pill to pill,” says Jess. “I was with the school therapist like multiple times a week, because I was just not coping.”

Dr Ogilvy tells Critic that clinicians take a holistic approach to all health and wellness concerns, emphasising it is important to outline the pros and cons of any proposed medication. “It can be difficult to be sure whether deteriorating mental health is attributable directly to the medication, as a result of the original symptoms or indeed a completely new problem. But we would certainly never want to ignore any such issues.”

Both Jess and another student, Lotto (they/them), told Critic that when they first began taking the pill, they suffered from extreme mood swings. Lotto says they experienced “constant tearfulness, like actually losing hours of my day, most days, to crying. Don't know how I produce so much fluid, to be honest. Kind of impressive.” Jess reports a similar experience: “I literally could just not stop myself from crying. I would just be consistently on the verge of tears. Like, every day.”

In 2022, former Critic Culture Editor Annabelle Vaughan wrote about her experiences with the side effects of the pill, particularly the “tumultuous mood swings” that came with it. “When that time of the month came, my mood became so bad that it was impossible to do anything at all. I was susceptible to bursts of anger and irritability, with my friends often being the ones to bear the brunt of it. I was forever in a state of feeling short tempered and aggravated, depressive and moody.”

Jess’s mood swings affected her personal relationships as well. After starting the pill, she says she “lost a lot of my friends roughly around the same time because I just got too much. It was just easier to isolate myself and not have to hurt anyone if I had a mood swing or if I got really upset.”

While Annabelle initially put it down to pressure of her lifestyle change in beginning university, once she came off the pill she said she had “never felt better [...] I now feel great, knowing that I won’t have to write one whole week off every month due to being in a depressive and anxious state.”

But quitting the pill cold turkey isn’t always the solution to these side effects. The process of coming off the medication can also have serious impacts on your mental health, as was Lotto’s experience. After they stopped taking birth control, Lotto says they felt “numb, but also like very, very on edge all the time. And just my capacity to do anything was rock bottom [...] It was just so, so obvious that I just couldn't look after myself.”

The pill’s side effects can have an extremely detrimental impact on everyday life. Lotto says that birth control left them entirely unable to look after themselves: “It affected everything […] My parents just got so worried that they flew me back up to Auckland. And I was there for like a month. Had to get extensions on everything. Pushed a lot of things back.”

But no one who Critic spoke to could recall being sufficiently informed or warned of these side effects, or the time it can take to regain mental stability after taking the pill. Nor were they offered counselling, or any other mental health support after being prescribed the pill – a medication which has become so normalised that Annabelle wrote she thought “taking the pill was one of the next natural steps in becoming a woman.”

For Jess, the lack of consultation from doctors before being prescribed the pill extended beyond emotional side effects, too. After being prescribed ‘Ginet’, Jess says she experienced horrible migraines: “I was having chronic migraines that would last months. Like I was incapacitated. For weeks on end.” The pain got so bad she was prescribed tramadol (an opioid medicine).

Jess later found out that Ginet could potentially cause seizures when taken by someone with pre-existing issues with migraines, which she suffered from. Jess was not warned or informed of this risk, and has since been told by health professionals that the migraines she suffered after taking the pill could have been absent seizures. This lack of oversight on the part of Jess’s GP did not allow her to make informed medical choices about taking this medication, nor was she provided the possibility of support should something go wrong.

Not everyone, however, has a negative relationship with the pill. Graduate Nina says she had a relatively positive experience after being prescribed the pill as a contraceptive at age sixteen. She experienced no issues or negative side effects for the three years she was on it and said that, “Honestly, I [only] stopped taking it because it was annoying to remember to take a pill every day.” Though she couldn’t recall being warned about potential side effects when being prescribed and threw out the info sheet in the box because it was “giving terms and conditions,” Nina would still recommend the pill to others, explaining “it did the job.” However, Nina acknowledges that, in retrospect, “it is important to be informed of what the potential side effects could be, because every birth control method is different for every single person.” These differences mean every experience of the pill is unique – for some it may be overtly negative, whilst for others like Nina, it may be stress-free.

Dr Ogilvy says many patients coming to Student Health have some prior knowledge of different forms of birth control, including oral contraceptive pills. “We will always aim to provide information around risks and potential side effects of any treatment prescribed. This advice may be verbal or in the form of leaflets or email links. Students are also encouraged to read the written information enclosed with the medication.”

The apparent easy process of getting a prescription for the pill does not extend to being prescribed alternatives. Jess tells Critic Te Ārohi she was denied any alternative treatment, such as seeing a specialist, alternate medication or surgery, despite pushing for these in her appointments. “I went to my doctors at the age of fifteen and was like, ‘Is there a procedure you can do? [But] they didn’t want to look at procedures or anything,” says Jess, explaining that the typical response from health professionals was that she was “too young”. Student Health GP Dr Jenny Ogilvy tells Critic that, unfortunately at this age, there are limited realistic alternatives with fewer side effects.

When asked what she would have liked to have done differently in treating her irregular periods, Jess said, “I would want them to run all the tests. Send me to a specialist […] instead of someone who isn't specialised in treating menstrual issues. I would rather have been sent to someone who was actually fully capable and knew what was going on and was able to figure out what was going on. Because if I had to get a whole bunch of procedures or inspections and stuff done to get to the root of the issue, which we still don't know what the root of the issue is, then it would've made my life so much easier.”

Unfortunately, referral to a specialist can be difficult. Dr Ogilvy says that while GPs “try their best to help as many people as they can, there will be students who require further specialist examination. Access to specialist care under the public health system can be extremely difficult and often students are reliant on private health insurance or the ability to pay out of their own pockets.”

Lotto faced similar issues in their attempt to find an alternative to the pill. With their first experiences with the pill leaving them feeling “just kind of awful all the time,” Lotto was understandably extremely resistant to try it again, their doctor suggested as treatment for their premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). PMDD causes significant distress and impairment in the early phases of the menstrual cycle and endometriosis. Lotto sought Zoladex and hormone replacement as alternatives. To Lotto’s frustration, their request was ignored. “I just could not find a GP down here [in Dunedin] who would do that for me.”

Lotto said they wished they had gotten “blood work checkups, follow-ups […] especially like in my case, just to make sure that everything was smooth.” Similarly, Dr Ogilvy hopes that our healthcare system can improve access to further tests, stating that she wishes we had “improve[d] access to ultrasound scans” and “specialist gynaecology clinics,” – especially for people with chronic pelvic pain – as diagnosis of endometriosis without laparoscopy (a surgical procedure) can be “extremely difficult.” Dr Ogilvy also says that she would like to see “better dissemination of information about contraception, menstrual and sexual health in general to empower people to make informed choices about their fertility.”

While not everyone has a bad experience with the pill, there’s no doubt many young people are being pushed to take medication that has the potential to massively impact their quality of life. As reported by interviewees of this piece, crucial information is not always provided to patients beforehand. The negative experiences of Jess, Lotto and Annabelle and others could perhaps have been remedied, or at least alleviated, had they known more about the effects of the medication they were being given. Their stories seem to point to a gap in our healthcare system, where a lack of access to specialised treatment for uterine related issues is causing an over-reliance on birth control as the go-to solution for a range of health issues and cosmetic concerns.

When the pill was first introduced during the second wave feminist movement of the ‘60s and ‘70s, it was a huge step in offering women sexual liberation and autonomy over their reproductive health. However, it’s important to recognise the shortcomings of the pill and the negative side effects it has on many who take it today as well as its benefits. Women and AFAB people’s medical history, life circumstances, and overall needs must be taken into account with the prescription of any medication, and the pill is no different.

The pill isn’t all doom and gloom, but bad experiences point to a need to rethink its quick-prescription, as well as for better understanding the spectrum of healthcare needs that fall under the birth control umbrella. It was revolutionary once, and with a greater acknowledgement of the diversity of those being prescribed the pill and increased access to specialised care, sexual health can be revolutionary again.