Thrill seekers are everywhere in Franz, to the point where bartenders used to “free-pour shots into open mouths like Cancun”, according to some guy I met in a spa pool. And to take care of those tourists, many students work in Franz over summers where they’ll invariably end up at Glacier Motors, the township’s only petrol station.

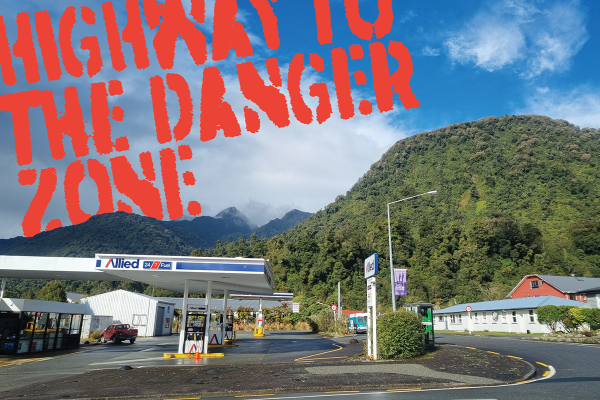

This station directly straddles the Alpine Fault. True, it’s hard to take a walk in New Zealand without stepping on a fault, but this one is especially easy to find; stretching 600-kilometres along the Southern Alps, it’s the longest straight line on the surface of the planet. It’s visible from space. And of the thousands of faults in our country, only the Alpine Fault ruptures with its signature blend of regularity and intensity. Sudden, violent movement. Eight metres of horizontal displacement. One and a half metres vertical. A magnitude 8 event every 300 years - or less. There’s an extensive and detailed record, and the last rupture occurred in 1717. Tick tock.

Glacier Motors’ two 50,000-litre petroleum tanks are right in the firing line. The metal filling valve caps in the forecourt are less than a single stride from the subtle rise made by the Fault in the pavement. To make things worse, the fault’s rise means the station is at the top of a small hill, so if the tanks were breached, any spillage would run downhill throughout the main street. And if the spill were to ignite, according to a local fireman, there would be “no way” to put it out. The town’s volunteer fire station (essentially a church and two garages) are on the other side of the fault from the rest of town.

The station is on the main road through town, unmissable as you head either direction on State Highway 6. To passersby, the only scary thing about it is the price of petrol. Of course, nobody can say exactly what will happen here; the fuel might not ignite at all. But when I last spoke to Otago’s own Caroline Orchiston, the foremost expert on Alpine Fault community resilience, I gave her a list of locations to be at during an Alpine Fault rupture, including a Wellington office, a Christchurch highway, in the Westland bush or in a Dunedin flat, asking her to rank them by where she’d like to be. Filling up at the Franz Josef petrol station ranked second worst, losing only to a boat in the middle of Milford Sound. That’s because when the Alpine Fault goes, landslides can trigger great, sloshing waves in the fiord.

Franz Josef is defined by natural hazards, so much so that it’s a stop on the University of Otago’s fourth-year Geology field trip. In my year, we paused outside of town to examine the oversteepened hillside behind it. Our lecturer pointed out how there was enough material on the calving face to bury the entire town and everyone in it, if it were to fail. He pointed out how LiDAR imagery shows what are basically geologic stretch marks on the top, evidence of creeping failure. He pointed out how (although it’s survived the last several ruptures) an earthquake could loosen the whole face with no warning. But we’re risk-takers, too. After we joked about how we’d better not all jump at once, we headed into town to fill up at the petrol station and then sleep directly under the hill. Because what are the odds, right?

The odds of a major quake caused by an Alpine Fault rupture are 75% in the next 50 years. 100% eventually. Dr Tom Robinson, from the University of Canterbury, recently told Stuff that the rupture will be “the largest earthquake in recorded history.” The odds of when and where are pretty clear, but that’s where any semblance of certainty ends. Predicting what this earthquake will do to the landscape, especially in the case of Franz Josef, gets murky. For example, there’s a chance landslides could dam the Waiho River and unleash a catastrophic flood. The odds are low, but still uncomfortably possible. The odds of slope failure are even lower, but even more catastrophic if they were realised.

When the Alpine Fault ruptures, which it will, we’ll be hearing lots of stories. Many of them will be about hope: about strangers helping strangers, about fast response times and a nationwide effort to build back better. Some of those stories, undoubtedly, will be about tragedy. But at least one of these stories will be particularly perplexing. It’ll be the story asking why the hell 100,000 litres of petroleum was sitting on our most notorious fault line.

The people in Franz Josef aren’t stupid. Except maybe for the guy in the spa pool who also told me that Jacinda was causing earthquakes. But besides him, Franz Josef probably boasts some of the highest Alpine Fault literacy in the country. Caches of post-quake survival supplies are buried across town. Multi-story buildings are rarer than clean boots. Franz has more helicopter pilots than police officers and a population that can take care of themselves and their neighbours. After all, who would you rather be stuck with: a tenth-floor bureaucrat who has never seen a deer or a Franz Josefite who could skin one with her eyes closed?

Back in 2021 when I talked to Wayne Costello, the operations manager for the Department of Conservation (DOC) in South Westland, he made it very clear just how ready the town is. He outlined all the preparation, all the community training, all the backup supplies, all the years of anticipation waiting for “the big one”. He’s right, the town is far more aware of what’s coming than anywhere else I’ve ever been. And he made a point that I’ve heard several times in my interviews on this subject: that the best things in life come with some risk, and all we can do is prepare. I can’t argue with that.

You're more likely to get in an accident on your way to this petrol station than you are to be there during an earthquake. But then again, when you get in that car, you take measures to ensure that if the worst did happen, you’d be in the best scenario possible. You buckle your seatbelt. You don’t look at your phone. You watch out for others on the road. You move the 100,000 litres of petroleum off the imminent earthquake risk. The last time I visited Franz Josef, I arrived in the pouring rain. About half an hour out of town, as I limped along the winding road, I passed a local speeding the other way. He was going about twice as fast as me, lights off, wipers down, seemingly blind to the lashing rain. Don’t look up.

You’d think the resource consent for the proposed petrol station would have been a good start, but you’d be wrong. The 1994 document does not mention the Alpine Fault at all, or earthquakes in general. The first six points of discussion are mostly concerned with aesthetics and disturbing the peace; only at point eight does it get close to mentioning risk. It reads: “It is not anticipated that there will be anything unsuitable about the proposal site.” And this isn’t the only petrol station on a fault line; Wellington has at least two (albeit atop reclaimed land, which could be a protective factor). But in the risk-dominated Franz Josef, it’s the only hazard that didn’t need to be there.

Every single resident I’ve talked to has not exactly been stoked about the situation. They told me that if money wasn’t an issue, the station would be moved. But they weren’t the ones who paid to build it, so they didn’t want to be the ones who had to pay to move it. When I last spoke to the manager of the station, Ryan, in 2021, he had only recently taken over operation of the Glacier Motors site following a change in ownership. And the community already has a long list of other woes: the flood-prone Waiho River is an expensive enemy and tourism is under threat thanks to the shrinking glacier. Publicising the issue too much could scare away visitors.

So, pun intended, whose fault is this? More importantly: who foots the bill? Is it up to the station’s new owners? Or the Council who signed off in ‘94? Or the government in Wellington? It’s genuinely not clear. But what is clear is that, one way or another, one day that petrol station will be moving. It’s just a question of moving it on our terms, or on the Fault’s.

Formal, finite action was proposed in the years following the Christchurch earthquake sequence. When attention shifted back to the Alpine Fault line which, unlike Darfield’s, was explicitly and long-ago mapped, with a regular recurrence interval and ample historical data, a group of scientists got together to propose a Fault Avoidance Zone (FAZ) for Franz Josef. The 200-metre-wide strip followed the surface trace of the fault through town and encompassed 30 properties, including the petrol station, a motel, a DOC lot, and the police building. If adopted, no new buildings could be built in the Zone and existing buildings would be incentivised to start moving away.

Dr. Virginia Toy, one of the scientists behind the FAZ, says this has happened before. In the ‘60s, planners encouraged movement away from the troublesome Waiho River, down towards where you can now find the pub and the Top 10 Holiday Park. Most of the main area resisted, but it was a win nonetheless. “They did eventually help the motel and holiday park on the other side of the river move through financial support,” Virginia explains. In the interest of preserving not just human lives but a nationally-significant tourism asset, “that’s what is needed elsewhere in Franz: central government needs to support the changes.”

The proposed FAZ caused an immediate uproar. Landowners, who were facing the direct financial consequences of the Zone, felt they had been left out of the discussion. Many felt they literally could not afford to worry about the fault, and when the FAZ was eventually adopted in 2015, the impact was indeed significant. Property records for 1 Condon Street, home of the Glacier Motors station, show that the value of the land dropped from $950,000 in 2015 to just $475,000 the following year. It still hasn’t recovered, sitting at $710,000.

Banding together in the name of their financial futures, a group of residents pulled what local Cushla Jones called their “only trump card” and threatened to take the Westland District Council to Environmental Court. The Council, split on opinion and low on resources, conceded. After six years of debate but within less than a year of activation, the FAZ was repealed. Local Helen Lash said she could “see the stress of this etched in people's faces… it’s taken a hell of a toll.” Dianne Ferguson, who owns the Alpine Glacier Motel, told reporters at the time, "We're pleased with the result. We feel this is the point where we should have started from—talking with each other —instead of taking six years and expensive legal action to get here.”

Councillor Gray Eatwell was “gutted” by the decision. He said that “it's not a matter of the people. It's a matter of what's right. If we don't acknowledge one of the world's best-known faults, I don't think it would make us very professional at all.” He didn’t last much longer on the Council. His fellow Councillor Durham Havill disagreed, saying that preparing for every risk eventually becomes untenable: “You can’t plan for everything.” He reckoned that “there are fault lines all around the country. When it eventuates is bad luck… We could have a tsunami, we just don't know.”

But we do know. We know this fault line better than nearly any other on the planet. The Council’s planning and environment manager Jim Ebenhoh raised the question of post-disaster funding priorities, and how much Wellington would shell out for a community who had explicitly voted against safety measures. Either way, the conversation was soon overshadowed by something spreading overseas. As New Zealand’s borders closed to tourists, economic strife had arrived in a different form.

For decades, Franz Josef has been Tourism New Zealand’s literal poster child. It’s front-page on the websites, it’s in all the ads. The tourist dollar, in turn, has offered ample incentive to settle in the township at the toe of one of the country’s most accessible glaciers, even today when that glacier has retreated so far up its navel valley you need a helicopter to get to it. And that visitor spending pumps money into the government’s coffers too.

When Covid hit, that income dried up. The 2021 Development West Coast Covid Impact Survey tallied some bleak numbers: 16 businesses closed, 23% of people gone, volunteer emergency services gutted. Without further assistance, the survey said, 84 percent of jobs would be lost, 67 percent of businesses would close, and at least 31 percent of people would leave the community “in the next six months”. Though one survey respondent was hopeful, saying in true West Coast style, “We’ll start a generator, kill an animal if anyone is getting low on food, helicopter companies will pick up supplies at their own cost, we’ll check in on the neighbours and we’ll still be here in a couple of weeks.”

Despite Covid, despite a recession, despite an utterly bizarre High Court fraud case involving their septic system and an Auckland cake baker, the town has persevered, and the tourists have returned. Business is better, the petrol is flowing again. Someone recently rated the station four out of five stars on Google: “It’s got petrol!” (The station also, incredibly and delightfully, still stocks Kodak film). And so a new plan, Te Tai o Poutini, has been proposed for increasing the resilience of the entire West Coast. Submissions are open now, but 1 Condon Street is still listed as a settlement zone. Simon Bastion, CEO of the Westland District Council, said that “there has been no formal request for the petrol station to relocate,” but that the new plan is “revisiting the zoning within Franz Josef alongside the natural hazards.”

Perhaps tellingly, one of the last times a zone was listed as high risk, it didn’t end well. Virginia tells me that a few years ago, signs were put up outside a hotel on the edge of town warning of sudden flood risk. Under the cover of darkness someone apparently took an axe to the signs, disposing of the pieces in the very river it warned of.

When I try to talk about Glacier Motors on the coast, people baulk. They don’t want “more doom and gloom”, and they don’t think their fault line is unique in a country full of them. A lot of them are more interested in asking me if the station’s pies are any good (“they’ve got a solid mince and cheese,” according to someone who passed through in July). I’ve been told, more than a few times, that we have bigger problems to worry about. And that’s true. But bigger problems require big solutions. We can’t move the Nelson Hospital or the Clyde Dam, both of which straddle faults. We can’t move all of Auckland off its volcanos or the entire city and port of Wellington away from earthquake danger. On a global scale, we won’t solve climate change overnight, either. It’s too late for that. Speaking of sitting on a fuse.

But the reason I think this particular risk is so fascinating and so worth talking about is that it’s not like Wellington, or global warming, or pandemics. There’s a single, simple, relatively-cheap solution: move the petrol station. Or, at the very least, put the tanks above ground. And don’t make the locals pay for it. It would involve interrupting service to the only station in the area, yes. Costs would surely exceed estimates, yes. It would be a major pain in the ass, yes. But it would also be one small thing to prove we can be forward-thinking, that we care about the impact today will have on tomorrow.

In the face of so many insurmountable crises, it would be nice to have a win.