Sorry, not sorry, but this article starts with a public flaying. If you were the breatha at the Soaked Oats gig at Mayfair earlier this year who called out if the band could “play that one again so I can boo it some more?” after they performed their final song, I hope you’re reading this so I can personally ask: what the actual fuck is wrong with you?

It absolutely blows to have gone to see a beloved musician perform only to come out of it with more to say about how the crowd acted than the music itself. I can barely imagine how much more it would suck as the musician.

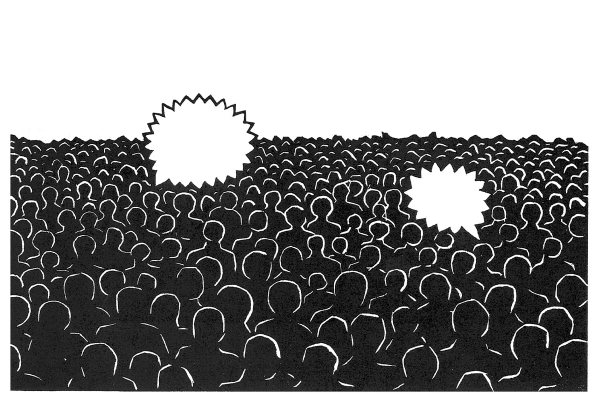

Regardless of where you go to gigs or however regularly you’re in the crowd, whether you’re a Pint Night loyalist or hang out just for the occasional nationally-touring act at Dive, you’ll have experienced someone in the crowd treating the musician like shit. At that Soaked Oats gig, we got it all: throughout it, they talked, they vaped, they interrupted. “Play Avocado! Play Avocado!” Surprise surprise, Soaked Oats refused. They came out for an encore despite the taunts, and were rewarded by a girl deciding it was a good idea to take a seat on stage with the band, even as frontman Oscar stared daggers at her. Visual cues from the band were not enough to override the egging on from her mates.

Sure, it’s only a small handful of people who conduct themselves this way at gigs. But it’s disappointing as hell. And I say the following as respectfully as I ever will in my entire life: Soaked Oats are a bunch of white guys, the demographic that are already at the top of the music food chain. If this is how they’re treated, what’s it like for everyone else?

The APRA AMCOS (Australasian Performing Rights Association and Australasian Mechanical Copyright Owner’s Society) 2020 survey into the Aotearoa music industry found that 45.2% of women in the Aotearoa music industry felt unsafe in performing and music making spaces - the very spaces where they’re expected to practise their art. Sexual harassment was the leading factor. Heckling and unsolicited comments on someone’s appearance is, at the very least, rude. At its worst, it’s sexual harassment.

Lucy Pollock is in the band Riot Gull. They were previously in the band Porpoise, and they also perform as soloist Sir Queen. Both Porpoise and Riot Gull have played shows across the motu. Lucy has experienced heckles and negative crowd interactions in all of their musical projects, in various venues and locations. In Christchurch during a Porpoise show, Lucy was tuning their guitar and introducing the next song when an old man in the audience yelled “you’re hot”. The band launched into their next song as quickly as possible attempting to defuse the situation. Later, another group of male attendees called out to Lucy again, calling them a milf.

Gemma Goldstein performs alongside Lucy in Riot Gull and they’ve experienced something similar here in Dunedin at The Crown. It was during soundcheck for Dankfest in August last year that a group of older men, who they were aware of as regulars of the pub, made comments about the appearances of the four-piece band. “They kept talking about us and commenting on individual member’s appearances as if we weren’t there on stage and could hear them. They were very close,” Gemma recalls. When asked if they thought the men knew they could be heard, Gemma and Lucy both agree that, regardless, the men didn’t care. Of the scenario, Gemma recounts: “It’s almost like, ‘What are they gonna do about it? If they hear me say this, so what?’”

Riot Gull are a women and non-binary band. “It bothers me so much. I feel like so much is expected performance-wise from femme-presenting people,” Gemma says. Lucy agrees: “It’s a lot of pressure to be there performing and look pretty on stage, as well as make music. Honestly, sometimes the attention is drawn more to peoples’ appearance than the music. Like that’s not my main purpose.” “It’s objectifying,” says Gemma. “It’s like, ‘I now see value in you because I think that you’re attractive’.”

This is an issue regardless of gender. TJ Zee, who performs as Zëxïi, has experienced audience members hitting on them while performing at Pint Night. Whether they’re on stage performing or cooling down after the show, they find the scenario inappropriate. This is in addition to having certain individuals feel entitled to details about TJ’s personal life, describing these people as “trying to break that fourth wall, without your permission.” TJ has also experienced front row guys making rude and sexual hand gestures during their set.

And then there’s the cover song requests. “You're trying to request them to play something like they're the queue button on your Spotify playlist,” TJ says of those who spend every lull in the performance yelling out what they want to hear, or those who hold their phones splattered with the text of a song request. “It’s a performance… it doesn't make sense to just yell out what song you want to hear. There's a whole structure to someone's show.”

For TJ, as a Black musician, those song requests aren’t simply frustrating; they’re flat out racial stereotyping: “They’ll automatically assume that I’m a rapper, when I’m clearly on stage singing alternative RnB music.” TJ also gets mixed up with other Black musicians in the scene, even with those performing completely different genres. This also comes back to the intrusiveness TJ has experienced from crowd members, who often ask where TJ’s from. “You don’t want to know where I’m from. You just want to know why I’m Black.”

There have been occasions at Pint Night that TJ has had to cut their set short as they could not compete with the poor crowd behaviour. TJ finds it disappointing, not only for themself, but for others in the audience as well. It only takes one person jeering or a small handful of people chatting and not paying attention to ruin the experience. “I actually like to put on a whole thing and treat it like it’s Coachella Festival,” says TJ. Preparing and rehearsing a set takes hours and hours of TJ’s time, as well as the precious time of his band, which is done on top of TJ’s studies. “Going through all that hard work and preparing it for all these people, then them being a barrier to the hard work that we’ve put in. Like, I did all this for you guys but you’re not reciprocating it right now.”

Other rude crowd interactions the above musicians have experienced include mocking and loud repeated remarks. The former they experienced in the intimate and small din of Inchbar, where a man imitated Lucy’s singing of a higher passage with an off-key croon of his own. It would have been in a crowd of no more than fifteen. The latter, Lucy and Gemma experienced together watching another band’s set while touring in Hamilton, where an audience member called out “fuck you”, thankfully humourously, between every single song. Gemma explains this “funny status thing within the crowd” can sometimes be harmless, but can escalate much farther as people try to one-up each other. The audience building rapport with the band is always appreciated, but there is a clear line when even positive statements veer into attention-seeking territory. Of those who make these constant remarks, Lucy asks: “Are you really doing this to show your appreciation for us? Or is this more about you making yourself stand out?”

Musicians know better than anyone else the difficulty of balancing their own notion of their art’s worth with the wants of the audience. When that music and the act of performing it is so personal, it conflates with your own self-worth. That’s your own being up there. Physically, as you move on stage. Emotionally, as you sing those lyrics and melodies. That’s something that happens as soon as you hop on stage and start sharing your music. It doesn’t matter how many songs you’ve recorded or how many people are listening.

It’s not as though musicians are naive to their audiences’ reasons for attending gigs either. Musicians are aware that certain venues and events are rowdier than others. They’re aware that people may just be there to get on the piss. But still. If you’re actively seeking out live music, because it’s legitimately pretty hard to end up at a gig without prior planning, why are you being such a dickhead to those providing it? Even more baffling is when you’ve fully dropped around $40 to be there, which was the case of the Soaked Oats gig. Gemma feels as though musicians are often seen as “for entertainment purposes only,” and Lucy comments that the commodified aspect of paying for that entertainment adds to that entitlement. “If you don’t like it, go away,” says Gemma. “No one’s forcing you to be here. But there’s no need to yell and take someone down like that.”

In not being able to form a positive connection with your audience, TJ shares that “it makes you, as an artist, feel like you are not doing your job right.” Here, where intoxication is clearly a factor, artists have to be additionally reflective of how it shapes their experience of performing. Still, TJ is understanding, saying that in a venue space it’s “probably the safest space” someone can just be messed up and have no inhibitions. “Why don’t I try to facilitate an even safer environment and give them something that will help them remember this moment? More so for how enjoyable it was, and not how fucked they got.”

As musicians, they’ve all got different ideas around minimising disrespectful crowd behaviour. “[Creating] gigs that have the mantra of being a safe space seems to work really well,” says Gemma, of both shows that she’s played and attended. Lucy and Gemma also point to the venues themselves looking out for their performers’ wellbeing up and around the stage and setting a tone in terms of what is and isn’t appropriate.

But really, it’s unfair for the ones providing that music and providing that space to be responsible for the crowd’s shit behaviour. I’m not saying you can’t go to gigs and get lit at all. Just read the room. Is this a Pint Night gig where the atmosphere is just as much about the pints as the music? Or is it some intimate ticketed gig where the musician is sharing new material for the first time? Are you hyping the band up? Or are you making them visibly uncomfortable? Are you simply just heckling? Or are you just reproducing the sexist and racist dynamics of the music industry right here within the walls of some silly lil’ pub in Ōtepoti?

If your entertainment is coming at the expense of the performers and the audience, Lucy has just one suggestion for you: “You fucking get up here and play, then.”