It's no secret that Dunedin has flat parties good enough to make boomers get mad on the news. But when it comes to going into town, we’re a bit shit compared to anywhere else. With only a couple of clubs, long lines, minimal food options, and a student body that can't actually afford to buy any drinks out, that might seem like no surprise. This wasn’t always the case, though. There are many factors that have contributed to the demise of Dunedin’s nightlife, and there are many potential solutions to revive it, for better or for worse.

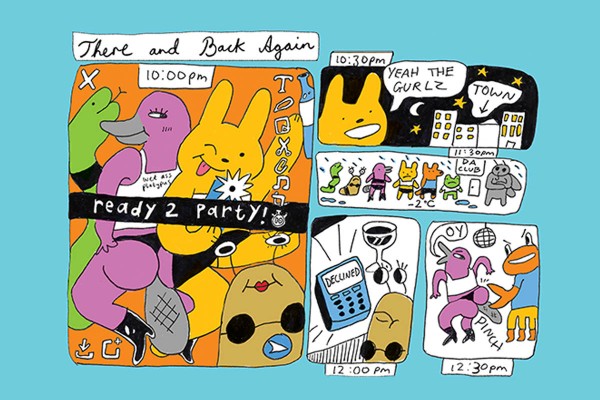

While many freshers told Critic that they go to town regularly, they also said that this was only because their halls kicked them out after a certain time on nights they were drinking. As for non-freshers, for the most part they don’t go to town at all. When pressed about why not, students cited the effort, cost, and cold as being leading reasons. Daniel told Critic the lines alone “makes it not at all worth it”.

The effort is huge. The walk from campus to the Octy is at least a kilometre long, and further if you’re coming from North of the Central Library. Sarah* said she had to be “in a really good drunk mood to go … I would much rather go to someone's flat to drink then stand in line for up to an hour just to be not let in because I'm too fucked.”

A number of women cited times they have felt unsafe in town or walking home from town as leading reasons why they preferred to drink in flats, where they usually knew everyone there. When the busses only run past eleven (but before midnight) for two days a week, but students don’t want to head to town until ten, it leaves next to no inexpensive or safe options to get home. For many, an alcohol blanket and a speedy pace is your way home. As Josh* put it, “If I was going to go to town and have a good night I’d have to be on at least two caps or three Nitros or both.” The two most common reasons students gave for not going into town, however, was that their friends didn’t go, and that it was too expensive.

Barely a decade ago Dunners had a vibrant (and cheap) pub and club scene, so what happened?

Former students can recall the days of “ridiculous” student deals at the many bars across Dunedin, like $1 doubles at The Cook, $3 drinks at Monkey Bar, and $4 jugs at the Gardies. If you visit the official Dunedin tourism website today, the page on nightlife states “Members of the younger demographic dance into the wee small hours at 10 Bar, Urban Factory and Monkey Bar. These and other clubs are found near The Octagon.”

The ‘NZ Pocket Guide’ describes Dunedin as “a great place to actually meet people from New Zealand, especially students in clubs like Monkey Bar, Urban Factory and 10 Bar”. As you may have noticed, literally none of these places exist anymore. 10 Bar is now Catacombs, but Monkey Bar and Urban Factory are now relics of Dunedin past, closing down in 2014 and 2015 respectively. The same can be said for The Bowler (which closed in 2009), The Gardies (2010), Mou Very (2012), Malbas (2012), Metro (2013), Capone (2015), Boogie Nights (2015), ReFuel (renamed U-Bar under new management in 2017), The Captain Cook (closed in 2013, again in 2017, and rebranded as a venue called Dive in June this year) and more.

When Rob Dale, the owner of Urban Factory, Capone, and Boogie Nights, closed all three in 2015, he owed a whopping $141,399 to IRD for Metro alone, and his case wasn’t an outlier. It is clear licensed premises (bars, restaurants, pubs, clubs) were struggling even before coronavirus took its toll on the hospitality sector. In a 2015 interview with Stuff, Dale laid the blame squarely on student drinking culture, claiming he was “the cheapest babysitter in town” and that students would spend less than $4 a person because they’d pre-load at massive student parties. It seems even when we did go into bars and clubs, students avoided spending much. In this era of late-stage capitalism, a vicious cycle has arisen where all the bars are closing or are too expensive because students aren’t drinking in town enough, and students aren’t drinking in town because all the bars are closing or are too expensive.

Don’t get me wrong, I love a red card as much as the next student, but there are many problems, or at least perceived problems, with our current drinking culture. At the risk of sounding like Mike Hosking at 6am on weekdays, first and foremost we have to mention the economy. With an ongoing pandemic/impending apocalypse, hospitality sectors aren't in the greatest position globally, though as I mentioned earlier Dunedin’s has been struggling for a while now. When licensed premises shut down or reduce hours it is bad for the owners and it is bad for the workers, who are often students working part-time to make ends meet. There is also a perception of student drinking culture as hooliganism, a nuisance, or even criminal. Most of the time this is just boomer rambling, and I would be the last person to tell you to listen to what some guy called Jim on Dunedin News thinks, but the litter and broken glass strewn across North Dunedin every Sunday morning doesn’t exactly say “we care”.

Then there is the damage to ourselves. The death of a student last year and a roof collapse incident in 2016 are accidents that remain in the student consciousness today. Outside of the tragedies that make national headlines, however, countless more minor ER visits put students out of action for weeks at a time every year. While it is extremely difficult to get quantitative data, there is far too much anecdotal evidence of sexual harassment on Dunedin streets. Additionally, alcoholism and substance abuse seriously affect our social and academic wellbeing as well as our mental health. While the people causing problems for others when drinking are outliers, these problems do exist.

Sergeant Ian Paulin, the alcohol harm prevention team leader of the Dunedin Police, believes the main problem driving harmful drinking and preventing students from revelling in Dunedin’s nightlife is that booze is too cheap at supermarkets and bottle stores. It appears Vice-Chancellor Harlene Hayne agrees with Paulin, stating in a Stuff article last year that "we need a combination of less availability, and making alcohol less affordable". Otago Uni, according to that article, pushed for the DCC to introduce minimum alcohol pricing in supermarkets and bottle stores under the Alcohol Reform Bill of 2010, to “counter pre-loading”. If they’d been successful, booze would legally have to be over a certain price. That would mean no more 8.6% Bavarias 4-packs for $10, no more Hardy’s bottles for $11, and no more boxes of goon for $25. RIP. Not only would minimum alcohol pricing shove my savings account into a high school locker and punch it in the stomach, it’s unclear what good it would actually do.

Community leaders like Paulin and Hayne imply that buying booze in bottle stores and supermarkets is cheaper than on licensed premises to an unprecedented degree. They are not alone in this assumption, but the assumption is incorrect. Using crowdsourced data on beer, the website Numbeo ranks New Zealand as the 16th most expensive country to buy beer in restaurants. For buying beer in supermarkets, we rank 10th. A Bloomberg report from 2018 found New Zealand alcohol prices are rising faster than anywhere in the world, too. Booze is pricey in supermarkets and bottle stores, it’s just even pricier at bars and most students can’t afford to get drunk in town anymore.

The submission the Uni made to the Alcohol Reform Bill didn’t just request minimum alcohol pricing either. They called for the purchase age for liquor to be 20 years or older, and for reduced trading hours for places that sold alcohol. These changes, along with minimum alcohol pricing, would simply make alcohol harder to get, but wouldn’t necessarily reduce harm. A Ministry of Justice report from 2014 found restricting alcohol access through minimum pricing would only have a “modest” effect on harmful drinking.

The Uni has implemented many other changes aimed at harm reduction of student drinking culture and encouraging more of it to take place on licensed premises, spanning from Campus Watch in 2007 to the Sophia Charter this year, and everything in between.

‘The Sophia Charter for Community Responsibility and Well-being’ was signed by Otago University, the Proctor’s Office, Campus Watch, NZ Police, Fire and Emergency New Zealand, Otago Property Investors Association (OPIA), the Dunedin City Council, and OUSA in late July of this year as a “shared commitment to the North Dunedin community”. The document lays out admirable ideals to make North Dunedin both fun and safe, however the plan laid out lacks any meaningful changes and consists primarily of steps that are already happening and, in many cases, already legally required to happen. These include the Uni stating they will “continue to enforce the Code of Student Conduct”, the NZ Police promising to “ensure that students and non-students are dealt with appropriately in a manner that maintains public safety and aligns with our obligations under the Policing Act 2008” and the OPIA agreeing to “work with Landlords to promote the Healthy Homes Standards and encourage a higher standard wherever feasible”. It’s like if KFC put out an advertisement claiming they now made their buckets with ‘100% real chicken’. Were you not doing that already?

Harm reduction under Otago Uni policy reforms may be succeeding though. A study published in 2018 lead by behavioural scientist Dr. Kypros Kypri analysed student drinking between 2004 and 2014 and found that the amount of students getting wasted on a regular basis has decreased from 40% to 26% in the wider student body, and from 45% to 33% in residential colleges, over that ten-year period. Whilst the study concluded that Uni policies may have contributed to this reduction, it also pointed out that comparable decreases have also occurred in other New Zealand universities and that the overall percentage of students drinking at Otago Uni has not significantly changed.

In a separate 2018 report published by the Uni titled ‘Alcohol abstinence not an option for students in culture of intoxication’, Dr. Kirsten Robertson from the Department of Marketing discussed how ubiquitous our drinking culture is. She also pointed out how hard it can be to abstain, even for a night, when there isn’t actually much out there to do if you aren’t drinking, and if you don’t drink you become somewhat ostracised in certain circles. I spoke to a student who can’t drink for medical reasons, who told me “you get a lot of people asking why you're not drinking and offering you drinks”, describing it as “kinda frustrating and sad”. She also said that FOMO was the biggest thing,and that it put her off going to some events “like concerts or bigger red cards because it's just not worth going sober”. In her study, Dr. Robertson claims that “there is a need to develop alternative cultures emphasising extracurricular activities”. Is it possible to make other evening activities better, more attractive, and more accessible?

To attempt to answer this question I asked students ‘What would you do on weekend nights, hypothetically, if there were good options other than drinking’? Responses ranged from movies, comedy gigs, and board games to sports, walks, and late night swims in Moana Pool. It seemed many students’ first reaction to the question, however, was “hmm” or “uhhhhhhhhh”, followed by something along the lines of “God there isn't much without drinking is there lmao'' or “idk Dunedin kinda sucks for non-alco activities”. It seems we find it hard to imagine a Dunners where we aren’t on the piss every weekend, with student Aimee replying “as soon as I read ‘other than drinking’ my brain just stopped functioning”.

A Dunedin where there are social activities that don’t involve alcohol is possible. Until then, student drinking culture isn’t going anywhere anytime soon. The tricky part is finding the solutions that actually reduce harm to students and improve Dunedin’s floundering nightlife. Raising the price of alcohol in stores isn’t a silver bullet, and with small profit margins, lowering the price of alcohol at licensed premises doesn’t appear viable either. One idea missing from the discussion is increasing student capital. WorldBank and Stanford University data shows that simply giving money to lower-income individuals leads to healthier lifestyle choices, including more responsible financial decisions, more time invested in education, and lower rates of alcohol consumption. Many students hover around what is considered the poverty line and student living cost loans are a band-aid solution that kicks the proverbial can down the road. If students had more money, we would have more freedom to spend it how we liked, and evidence suggests that we would be responsible about it. No one is saying that it would stop drinking entirely, but it would allow more students to afford alternative social activities, better (and safer) flats, and to spend money on food and drinks in town - reviving Dunedin’s nightlife in the process. There are plenty of ways this could happen, from lower university fees to fairer rent to higher and more universal allowances. Until then, Dunedin’s nightlife will continue to die a slow death.

Whilst it can be tricky for public institutions like Otago Uni to advocate for political policies, it’s hardly unprecedented. The Uni demonstrated this when it made the aforementioned submissions to the Alcohol Reform Bill in 2010. If the stakeholders of the Sophia Charter were truly committed to the ideals set out, they would advocate for, and help put into action, meaningful changes to make flats better, making Dunedin more accessible and safe and students more financially comfortable. Unfortunately, these solutions are both boring and mired by political overtones. Improving public transport and making it free for students would be a start, as would advocating for policies that directly benefit students’ bank accounts without drowning us in debt.

As it stands, for most of us Dunedin’s nightlife is not worth the cold walk into the Octy and hour-long lines that often ensue. It’s not worth the harassment that many students, particularly women, often face. It’s not worth the little money that most students have left after rent, power, food, and drinks are all paid for. And it’s not up to students to make it worth it.