“I was so upset I almost forgot that I might be pregnant. I was expecting to be slut-shamed, but I wasn’t expecting to be racially profiled, and shamed for being a woman, a student, and a person.”

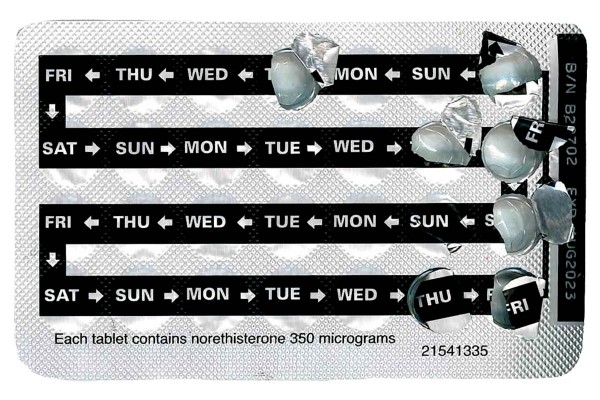

The Emergency Contraceptive Pill (ECP), known as Postinor-1 or, more commonly, the morning-after pill, is a progesterone pill. It works by delaying ovulation so there is a lower possibility for an egg to be fertilized. There is no fetus involved, nor are there any serious health issues associated with the pill. It ultimately has the same result as ordinary daily contraceptive pills, except you only take it once, so there isn’t the excitement of wondering if you forgot to take it last night.

Svetlana* discussed her experience as a woman in the higher weight bracket. When she asked for the ECP she was weighed and told she was “too overweight, which was obvious from a cursory glance” and then had her personal responsibility questioned. She was then refused the pill. The pharmacist then informed her that she would have to be more responsible than most girls. All Svetlana could say to the pharmacist was "okay, I guess I'll just have to get an abortion if I'm pregnant then," and left. It wasn’t until a few weeks later that she found out that she could have taken the pill, just at a slightly higher dosage.

The Family Planning website states that taking a single ECP will be sufficient if you are an “average weight”, but if you are over 70kg you will need to take two doses for it to be effective. It is surprising that they determine 70kg the average when the average weight for Kiwi women is 74.6kg, but okay. Annoyingly, the information package that comes with the ECP says that the data available on the effect of weight is limited, and what is available is largely inconclusive.

When Ellie* walked into a pharmacy after a night out, her expectations were low. After asking the pharmacist for the ECP, she was escorted into a very small room at the back of the pharmacy for the “sensitive” conversations. She was then weighed and asked questions about her mental health, most of them irrelevant to the prescription of the pill. She was on fluoxetine, a common antidepressant, which prompted a conversation on depression and weight gain. “He informed me that I was depressed because of my excessive weight,” Ellie said.

Ellie was also asked if she was Māori, despite writing ‘British European’ on her form. She was then asked if she was on any “holistic contraception”. She wasn’t sure what he meant by that. In this case, he was possibly referring to the cycle tracking method of birth control, which is mostly ineffective.

When offering alternatives for contraception, Ellie was told that “people of your weight class can get an IUD”. A IUD is short for intrauterine device, and is a copper T-shaped birth control that gets shoved up your uterus. The pharmacist provided Ellie a “Steve Irwin-like” description of an IUD insertion. She believed the pharmacist was trying to sell her “the idea of just chancing it and having a baby… I couldn’t even say anything, it was just a very quiet acceptance.”

After all of this, she wasn’t even provided the pill. The pharmacist explained he couldn’t provide the dosage she would need. “At the time, I wasn’t aware that a student health doctor could have provided me with an appropriate dosage,” she said. Ellie didn’t seek further help at that point - she just drove back to her college.

The situation happens even in places dedicated to sexual health, like Family Planning. Lucy* spoke about the situation she encountered when going to get the ECP from a practitioner at the Family Planning clinic in Dunedin. “Her whole demeanour and tone was extremely dismissive, like I was some child,” Lucy said. She was repeatedly asked why she wasn’t on the pill. “I have been on two different IUDs previously and she knew that they didn't work well with me cause she could see my records.”

“I was so stressed and visibly uncomfortable but she didn't register any of that.”

Lucy continued, “This interaction has affected me so much I have been unable to go to Family Planning again. I just feel like it will be uncomfortable and I don't want to hear offhand comments.”

Chief Executive of Family Planning Jackie Edmond said “We’re sorry that Lucy* didn’t have a better experience at our Dunedin Clinic and we hope that she’d give us another try. We’d really encourage clients to tell us when they’re not happy. Complaints or feedback is how we learn and make our service better.”

Ellie said, “I think it’s the element of vulnerability just being met with complete invalidity.” Young women especially are in a vulnerable position, facing the daunting potential of an unplanned pregnancy. The purpose of medical and pharmaceutical professionals is to provide help and support people in a non-judgemental way.

Cases like these depict the kind of gatekeeping and moral projection that all women worry their doctors and pharmacists will say. Legally, there is no problem with them saying any of this. Pharmacists and doctors have the legal right to refuse a patient any contraceptive, either hormonal or otherwise, and not face consequences because of the legislation surrounding Conscientious Objection (specifically, the Contraception, Sterilisation, and Abortion Act from 1977).

Unfortunately, the same people with the power to refuse to help are the same people we are all raised to believe will give us informed, fair, and responsible advice.

The NZ Pharmacy Code of Ethics states that pharmacists must “take appropriate steps to advocate for patients to access services and resources appropriate to their needs”. If a person asks for a medication that they need at that point in their life for any reason, it is their responsibility to advocate for their needs. The Code does not encourage or allow personal judgement, gatekeeping, discrimination, or dismissal.

I reached out to a Centre City pharmacy for comment regarding their experience with the ECP. According to one of their pharmacists, all pharmacists are required to undergo a special training and accreditation process in order to distribute the ECP. This is because, as a subsidized prescription, the government has a responsibility to oversee it. There is also a checklist of questions that the provider is required to ask patients before administering the pill, to make sure it is a thorough consultation. She can’t recall any uncomfortable situations where a woman was asking for an ECP.

Embedded in the stories of Svetlana, Ellie and Lucy are the deep effect of slut-shaming and the mistrust of women. The idea that we can’t take care of our bodies, or we can’t be trusted to make our own decisions is part of what has poisoned the narrative surrounding emergency contraception. There needs to be regulation, clarity, and, at the very minimum, an increase in the education provided for contraception and reproductive health.

*All names have been changed for privacy reasons.