Content warning: suicide, Christchurch shooting

My best friend committed suicide in 2017. When I started working at Critic the following year, I wanted to write about grieving that irrevocable loss. I wanted to do something with my pain. Scrape it off me and mould it into something useful. Maybe I could help someone, I thought. Maybe a suicidal person could read it and remember how their life ripples into others. Maybe a grieving person could realise they weren’t the only one waking up filled with sorrow, and feel less alone.

I interviewed a few people. I spoke to Jean Balchin, the Otago Rhodes scholar who, after losing her brother to suicide in 2014, has volunteered for LifeMatters and talked about her loss publicly. I spoke to Cam Haylock, a Christchurch-based youth pastor who lost his flatmate and fellow youth worker to suicide in 2016, and then supported scores of teenagers through the loss he was feeling so strongly himself. These people were years further down the track, going about life, doing amazing things. I wanted to know how to get there, learn the tips and tricks, ‘How to Get Over Grief in Ten Easy Steps’.

But the article never got further than being a bunch of notes on my phone. I realised I wasn’t interviewing them for a hypothetical audience, but for myself. I was going to have to actually take time to face my grief, rather than just writing an article about it.

I’m in a better place now. Starting another year of Uni, another year of work, I feel clearer. Over the last few months, I have only reflected on my memories of my best friend with joy, something I could never imagine at the beginning.

But the Christchurch shooting reacquainted me with feelings I was getting used to living without. I’m sure I’m not the only one. The heartbreak of waking up and remembering what happened. Trying and failing to understand how the human mind can be overcome by lies, and how the human hand can create such pain and death.

Thankfully, I have learned a few things as I’ve trod the grief path, or rode the rollercoaster, or faced the waves – whatever cringey metaphor I’ve internalised from counselling. And it feels like the right time to share. Every grief is different but, from one grieving person to another, whatever grief you’re facing, here are some things that are good to remember.

1. We grieve because we love

Humans have an amazing capacity to love. But when we are separated from the things we love – be they people, places, pets, dreams for the future, physical abilities or something else – we grieve. And it’s an important process to get right.

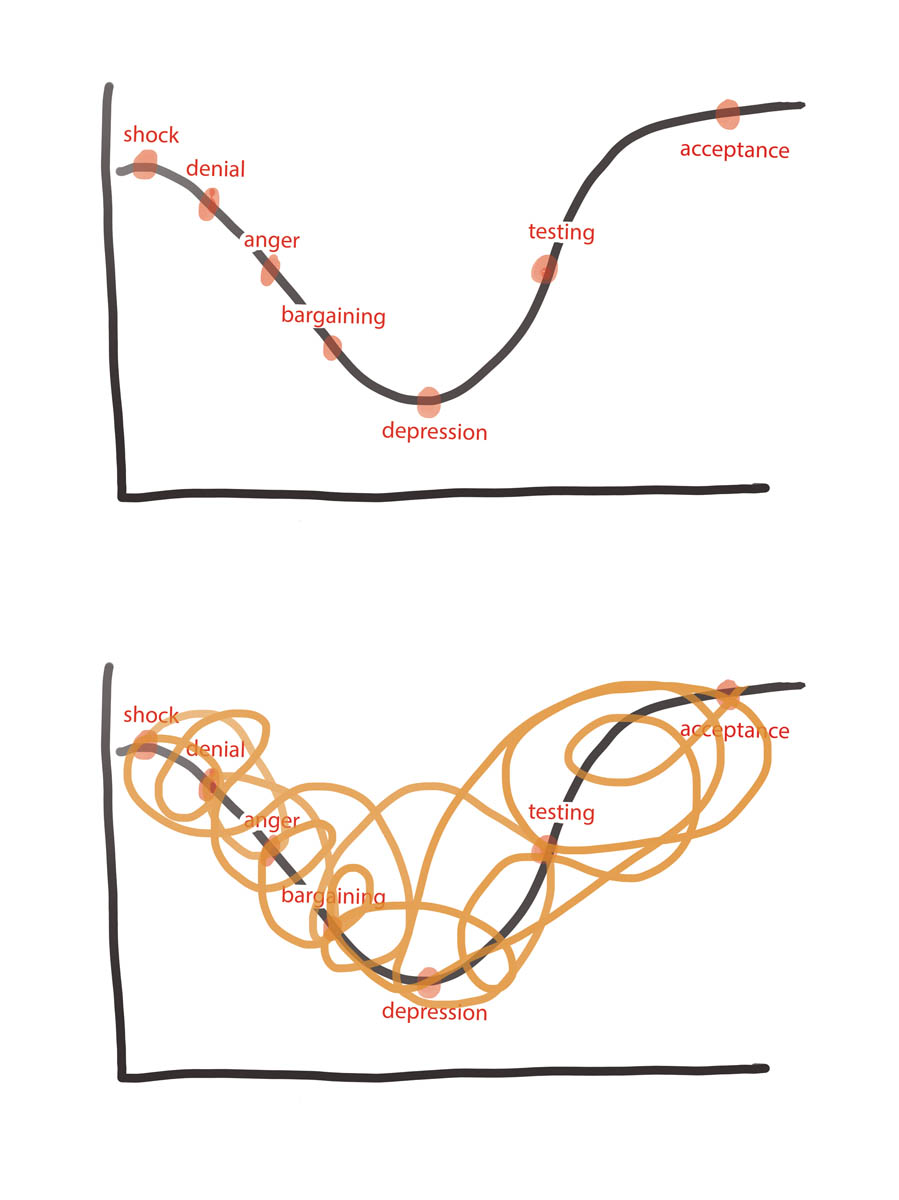

In 1969, Elisabeth Kübler-Ross wrote a book called On Death and Dying as she was frustrated by a lack of instruction in medical schools on the topic. Her book formed the basis for the pre-eminent grief model that describes stages of shock, denial, anger, bargaining, depression, testing, and acceptance. It’s a pretty good basis for understanding grief, but you can already see that those stages can be very general.

One counsellor described it to me like this - here’s the model, and here’s what it’s really like:

Even if your stages don’t match the Kübler-Ross model exactly, the reason the model has stuck around is because it reminds us that we progress through different feelings of grief. We need to watch if we’re getting stuck in one emotion, especially anger or depression. It’s okay to feel angry for days, even weeks, throughout the grief process, but when it turns into months or is holding you back from experiencing joy, you should seek some help to shift your thinking. Give yourself time to face each emotional change as it comes, see it for what it is – grief – then accept it, and let it pass.

Sometimes I forgot that my thoughts were linked to grief. I would have anxiety and dark thoughts or fixate on things like my relationship with my boyfriend or what my friends or flatmates thought of me. I would freak out, until I remembered or (more likely) was reminded by loved ones, that it was tied to my grief. Our brains are really weird, that’s why it’s good that:

2. You never grieve alone

It’s clear that our whole country is grieving the Christchurch shooting. If you’re heartbroken by that, or something else, don’t forget that people will get it. Everyone’s lost someone, or knows someone who has lost someone. In my experience the more you open up, the more empathy you will encounter.

It can be hard to share. If you’ve lost a loved one, especially to suicide, you may not be at the point of talking about them yet. Words are hard to find when your heart feels empty. Other people might not want to bring your loved one up because of how they died, or because they don’t want to upset you further. That can make it tough when you get to the point where you do really want to talk – people’s silence can make it seem like they don’t care. That isn’t true.

People might not know exactly how to help, but that doesn’t mean they don’t want to. Often, they’re taking cues from you as to how to treat your grief, so it is okay to tell them what to do. Cam Haylock said he instructed his friends to ask him about how he was doing with his friend’s suicide whenever they saw him. I felt the most isolated about six months after my best friend died, and that was when I tried this too. It helped. Sometimes I was really sad and needed someone to ask me how I was doing so I could share with them. Other times I was fine but I was always glad they’d asked.

3. You’re going to live through this

When I first found out, I didn’t know what I was supposed to do. I tried to go to class as normal, but all I could hear was white noise. It started to almost physically hurt me that the sun was out and people were going about their lives. How could they carry on when such a precious, creative and loving person had left this earth? The next day, I just cocooned. I didn’t leave bed all day.

It is okay to cocoon and avoid everything. Sometimes you need a good cry. It won’t be this bad forever. Those intense feelings will subside if we give ourselves space to experience them. You will get to a point where you can look back with joy, and have hope for the future. Don’t rob yourself of that by holding your grief in and not facing it.

4. Grief brings up other grief

It is very important that we let ourselves grieve because, like most things in life, it doesn’t go away if we ignore it. If we just bottle everything up, it’s going to come out eventually, usually when another traumatic event happens. As one counsellor said to me, new grief brings other unprocessed grief up to meet it.

After my best friend died, I saw our friends process other trauma they hadn’t faced from the past. Things like sexual assault, questions of belonging or their own mental health issues. I realised I hadn’t fully grieved the loss of security I experienced as a teenager facing the Christchurch earthquakes. The tragedy of the Christchurch shooting can bring up other tragedies we’re grieving. That’s natural. Don’t feel like your pain is not valid because you think it’s not ‘as bad’ as the pain of the victims’ families. You still need to grieve.

5. There’s no rush

The stages of grief are not assessment criteria you need to whiz through as soon possible for extra credit. Grieving can last a long time because the people we lose are never coming back. That won’t change as long as we live. As we pass birthdays, anniversaries, graduations, significant political events, start new relationships or face break-ups, get married, change careers, have kids or age without the ones we love, we may experience feelings of grief again. That’s okay. It takes as long as it takes.

I couldn’t write this article a year ago because it was too soon. I was measuring myself against people who were years into their grief, wanting to get to the acceptance stage when I was really still in shock. So, know your limits and take care of yourself. There’s no rush.

6. Counsellors aren’t scary, but they’re also not ‘one size fits all’

Counselling is very helpful. A good counsellor can help counter your painful feelings with truth and give you tips to keep going. But not every counsellor is going to work for you. I think I’ve seen ten different counsellors. Some of them offered help, others not so much. Weigh up their words and methods and see if it works for you. If not, don’t panic. There will be someone else that is better suited to you.

7. When things are good, it doesn’t mean they’ll go bad

Sometimes, when I feel good, anxiety convinces me everything’s going to turn bad. Part of this is because before my best friend died I was feeling so hopeful. She’d been seriously mentally ill for five months but we all thought she was turning a corner. I was starting to not worry about her all the time, letting myself relax. Then, she killed herself. That out-of-the-blue shock has made it hard for me to settle into feeling safe and comfortable since.

As life in New Zealand starts to go back to normal after the Christchurch shooting, and we get back into our everyday routines, fear will linger on. This act of terror was unanticipated, unprompted. We might feel like we need to be constantly on edge, prepared for the worst. But that’s no way to live. Even if bad things happen when we’re in that state, did feeling constantly fearful help us prevent them? No. Obviously, as a country we need to make, and are making, changes to prevent this kind of hate erupting again. But that change shouldn’t be to enter a state of constant vigilance and fear. Instead, we need to embrace light and life.

8. Let light in

When we lose people in tragic or violent circumstances, it can be easy to let the darkness of it all engulf us. But the best way to honour those we love is to let light and love win – not death and darkness. Spend time doing things that bring you joy. Relax with friends, make some art, sing, exercise, work hard at your study, make new friends, spend time alone, cook, go to the beach, travel overseas, talk about your lost loved ones, learn something new, help someone else face a tough time. Lean on the community that understands you – whether that is your church or mosque, your family, your friends or a student group you’re involved in. Humans are relational creatures and the best way to grieve is with others.

It’s all very well for the dead. Wherever you believe they are, it’s not here. It’s the ones left behind who have to try and make sense of it all and keep living. That can be messy and exhausting, but grief is the best process humans have got to keep going. And, the best part is, we’re never alone.

If you think someone is in immediate risk, please call:

Emergency Psychiatric Services - 03 4740 999

or Police – 111

If you, or someone you know, is experiencing mental distress or just not feeling quite right, get some professional support. There is funding available via StudyLink to access a subsidy from WINZ to cover the costs of private therapy for students if you can’t afford it.

Student Health staff can provide same-day appointments for those in urgent mental distress:

Student Health - 03 479 8212

Other services include:

OUSA Student Support, 5 Ethel Benjamin Place. Open 9:00am - 4:30pm, Mon-Fri. 03 479 5449, help@ousa.org.nz

Mirror Counselling Service (for ages 3 to 19) - 03 479 2970

Thrive Te Pae Ora (for ages 12 to 19) - 0800 292 988

1737 Helpline - free call or text 1737

Youthline - 0800 37 66 33, free Text: 234

Kowhai Centre - 03 477 3014

Lifeline – 0800 543 354 (0800 LIFELINE) or free text 4357 (HELP)

Suicide Crisis Helpline – 0508 828 865 (0508 TAUTOKO)

Healthline – 0800 611 116

Samaritans – 0800 726 666