Happy Avatar; Dead Human?

It is 3pm. My parents are still at work; the house is silent. A tired groan suddenly reverberates throughout the house. I feel myself grow frustrated. He’s waking up. Dishes clink together in the kitchen; I sink low in my chair at the sound of approaching footsteps. My brother appears in the lounge with a large bowl of cereal in his hand. The hair on his head is a fiery mess. He grunts at me. I’m unsure as to what he wants, so I retreat to a corner of the lounge to let him eat his cereal in peace. A few minutes later, after finishing his breakfast, my brother has dragged the dining table in front of the television in the lounge. On this table his laptop omits a breathy hum as it whirs to life. At 3:30pm the day has just begun for my brother. I remain in the corner of the lounge, observing him.

Many days during the summer break involve the same routine for my brother. They start at two or three in the afternoon, and end at some unknown time in the early morning when everyone else in the house is fast asleep. Although my brother would probably despise this label, during this free time, he is a gamer. He loves the strategies, combat, and online interaction with various virtual, often astoundingly beautiful, worlds. And, apart from those who share his interest, it’s hard for people – especially my parents – to accept this habit. After several fervent family arguments over dinner, with my brother presenting strong defenses for his cause (typical of a Philosophy major – confusing people with his questions on semantics: “But what does it mean to be happy, anyway?”), I have begun to wonder if any of us are in a position to question this kind of habit or how my brother spends chunks of his free time. I have also come to be fascinated with the allure of online gaming.

Most online games can be split into a range of popular genres. Three particularly common genres are massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPGs), multi-user domain games (MUDs), and first-person shooters. MMORPGs involve networks of people, all interacting with one another to play a game to achieve goals, accomplish missions, and reach high scores in a fantasy world; examples include World of Warcraft, Guild Wars, EverQuest, RuneScape and Dofus. MUDs, on the other hand, combine elements of role-playing games, with fighting and killing in a real-time virtual world that is often text-based; this type of game is also what many MMORPGs evolved from. “First-person shooter” is hopefully self-explanatory in its name, and includes Call of Duty, BioShock and Halo.

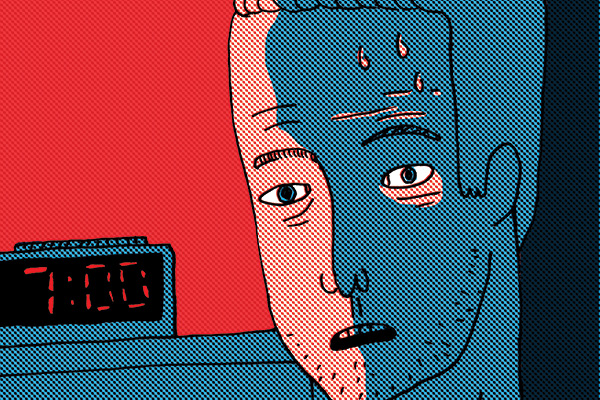

My eyes snap open. I look at my cellphone’s clock. It’s three in the morning. A maniac laugh echoes throughout the house followed by a frantic frenzy of mouse clicks – the collective sounds of someone seriously getting screwed in their game. I wonder what my brother has done. The next morning he explains. He was in the middle of an online quest on Guild Wars 2. On this particular quest, there were four others in his team. He starts laughing hysterically as he recounts the scenario to me: “On this quest,” my brother begins, “the group must make their way through a small maze of tight corners and hallways. At the end of each part of the maze are electricity turrets, which all go off simultaneously every two or three seconds. The aim is to turn off the switches in the maze. If you’re new, you don’t know where to go to dodge the electricity bolts. (He pauses dramatically.) You often get smashed up by the bolts, your body flies up in the air, and you lose a lot of health. However, if this happens, you’re never completely dead – you have last-moment health. You wait and hope for an ally to heal you. But the ally has to get to an unsafe spot and often they get hit, too. Then both of you keep getting hit. Soon two people are dead and the maze can’t be completed. The whole team comes to heal you. At that point, everyone starts to die.”

My brother is part of this world, a global community he can interact with without even stepping out of the front door. It’s almost utopian. Gamers, regardless of their personal backgrounds, are “reborn” again each time they start a game. Everyone begins at level one with equal opportunities to advance in seemingly infinite directions. There is no privilege, no class structure. Gamers can also go wherever they want in the virtual world despite any physical incapacitation (like a broken limb, a wheelchair, or morbid obesity). They can accomplish quests or win battles, which provide them with money, level-ups, and interesting gifts. There are moments of hilarity, of comradery, and of failure (never complete, perpetually redeemable). In fact, to some extent, most online games can fulfill every desire a person could have – what’s more, everything is so much more attainable than in real life. Why choose taxes and laundry chores when you can build and wear full Rune armor in Runescape, or (male or female regardless) you can fight as the beautiful Ahri the Nine-Tailed Fox in League of Legends?

However, despite these idyllic aspects of gaming, it seems there is a general feeling of unease felt by non-gamers towards those who enjoy adventuring in a virtual world. In some ways, this is understandable. Games are made with the intention of hooking the user so they keep coming back, over and over again (just look at the low-budget documentary Away From Keyboard which films a group of gamers who constantly return to World of Warcraft over six years, while their social and working lives crumble). Game-developers, in their quest for lucrative business, can act similarly to those who run tobacco companies. In an interview with Mez Breeze for The Next Web, Transmedia Game Designer Andrea Phillips explains that game developers have “rampant and intentional use of the compulsion loop, which is a term ultimately derived from Skinnerian psychology ... The core appeal of gambling is the compulsion loop, too … It’s that tension of knowing you might get the treat, but not knowing exactly when, that keeps you playing. The player develops an unshakeable faith, after a while, that THIS will be the time I hit it big.” While the compulsion loop isn’t inherently negative (it’s actually a fundamental aspect of human nature) it can be used in negative ways – just watch any long-term gambler (dead eyes, pallid skin) at a slot machine.

Other essential elements to the hook factor of these games are the intense satisfaction in achieving a goal or moments when a gamer is so close to achieving said goal but fails at the last moment and therefore must try repeatedly to achieve it. As Mez Breeze writes: “This idea of ‘fun failure’ links directly to the psychological concept of attentional bias. Attentional bias is where an individual constantly prioritises their attention towards emotionally dominant stimuli in one’s environment and to neglect relevant data.” The low amount of effort required for gaming, and the large amount of reward that’s gained – along with the flow of easily attainable goals, and online friends who convince you to play for longer to keep up with the team – are also factors that keep a player returning to a game.

The general unease and suspicion of gamers may be aggravated by the constant flow of shocking new stories. Daniel Petric, from Ohio, was convicted in 2007 of shooting his parents (killing his mother) with his father’s 9mm handgun after they confiscated his copy of Halo 3. His sentence was 23 years to life in prison. Alexandra Tobias, at 22 years old, shook her three-month-old baby to death because he cried while she was playing games on her Facebook page. She was sentenced to 50 years in prison. Tobias, a person with a troubled history, told the judge: “I hate myself for what I did, but not for who I am.” These stories continue. Rebecca Colleen Christie, from New Mexico, received a 25 years prison sentence for the death of her daughter (malnutrition and dehydration) while she spent hours chatting and playing on World of Warcraft. Reports of this case from the U.S. attorney’s office described Christie’s house as having an “overflowing litter box and pervasive smell of cat urine [... with] so little food that the child ate cat food.” In Shanghai, Qiu Chengwei stabbed Zhu Caoyuan when he discovered that the fellow gamer had sold his virtual sword (won in the game Legend of Mir 3) for 7,200 Yuan. In February 2012, Chen Rong-yu died at an Internet cafe while engaged in a marathon gaming session on League of Legends. He was found by one of the cafe staff slumped in his chair with both arms stiffened in a pose that suggested Chen was still attempting to reach the keyboard whilst undergoing a suspected cardiac arrest.

“My dad brought me here to see the doctor. But he locked me here instead,” sobs a young Chinese man in the short New York Times Op-Doc by Shosh Shlam and Hilla Medalia called “China’s Web Junkies” (a segment part of a much longer documentary to be released this year called Web Junkie). As the man speaks to the camera he sits on a bunk bed in the Internet Addiction Treatment Centre in Beijing, where he will be for three to four months, often behind bars and guarded by soldiers, in order to recover from his addiction. His days are highly regulated and disciplined, with controlled meals and regular group-therapy sessions. There are also sessions for the parents. One professional at the Centre says, “Some kids are so hooked on these games, they think taking a restroom break will affect their performance at these games. So they wear a diaper. That’s why we call it electronic heroin.” The “loneliness” of these addicted kids is also emphasised. The Centre, established in 2004, was one of the first of its kind, but now there are hundreds in China and South Korea, with numbers increasing around the rest of the world, too.

In 2008, four years after the Beijing Centre’s establishment, China declared Internet addiction to be a clinical disorder, believing it to be a major health threat to its teenagers. However, after filming the Web Junkie documentary, its directors were still not convinced that the children were being accurately evaluated (especially if other complex social and behavioural issues were also apparent.) They also questioned the effectiveness of the treatment itself. This uncertainty as to whether compulsive gaming and excessive Internet use are really addictions in the clinical sense is not unique to the Web Junkie directors; it’s everywhere. The American Psychiatric Association, in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, identifies Internet Gaming Disorder as a condition that requires more clinical research and experience before it might be considered for inclusion in the main book as a formal disorder.

On the other hand, Jerald J. Block, writing for the American Journal of Psychiatry, believes that Internet addiction in general should be viewed as a common disorder. Furthermore, Block identifies four components that make up the disorder: “1) excessive use, often associated with a loss of sense of time or a neglect of basic drives; 2) withdrawal, including feelings of anger, tension, and/or depression when the computer is inaccessible; 3) tolerance, including the need for better computer equipment, more software, or more hours of use; and 4) negative repercussions, including arguments, lying, poor achievement, social isolation, and fatigue.”

New Zealand, however, has no specialist treatment centre for this problem (disorder or not). One exception to this may be Nelson’s Nayland College, which started a gaming club back in 2012 to help students “addicted” to gaming by both recognising the importance of gaming while encouraging the development of their social skills and a sense of belonging outside of virtual realities.

“You want me to say gaming is bad for you, but you’ve got to first define what the good life is,” my brother asserts in a conversation over lunch one day. “Maybe the Internet simply clarifies our immobility – what we can’t do – then games actually address this issue. And if you can’t win in your physical reality, why is it not acceptable to enjoy winning in a gaming one? Maybe, for many, a gamer’s success is intangible, but to them, they can see it right there on their screen. It’s not like gamers all turn to games because they’ve been rejected by society – many might view themselves as simply lacking opportunities.” In a similar vein of thought to my brother, theorists like McKenzie Wark (author of Gamer Theory) questions this “addiction” status. “Is ‘addiction’ even the right term? Or is it just a metaphor?” Wark queries. “Why do we stigmatise certain engrossments more than others? When my kid reads books all day, my partner and I are happy about it. When he plays games all day, we are not. Who is to say one is better or worse than the other?”

For several weeks in the break, I had trouble sleeping. Each night I’d turn my bedroom light on after trying to sleep for an hour or so. Despite the imminent exhaustion, I’d continue to read my book until the early morning. After a while, I’d look at the clock and my heart would sink at how late it was. Two in the morning. Again. Sometimes, as a sort of distraction, I would get up to go to the bathroom and each time I noticed everyone was asleep – including my brother. I would finally fell asleep at a very late hour, which meant that I would miss half the next day, and often oversleep. It’s the same pattern seen in gamer stereotypes. But instead of games, I had my fantasy fiction novel.

“Addiction” may be a question of semantics, “disorder” may be a question for psychiatrists, but, intentional or not, games – like most consumable products – are designed to hook. However, what these games do that many other things can’t, is provide, as my brother tells me, “opportunities to make the powerless feel powerful.” Which leads to the basic question: why do these people feel powerless in the first place?