The ability of broad media campaigns to reinforce cultural hegemony is enormous and we must scrutinise the world of products, services and their accompanying brand aesthetics. What kind of societal ideals, vices and fears are the creators of these well-crafted messages tapping into? By continuing to manipulate these ideals, vices and fears, they construct an image of normality.

The wittiest media campaigns are those that make consumers forget they are unscrupulously hunted prey. The purpose, often through passive and subliminal modes of engagement, is to create wants and needs, from which we purchase products and services. It is easy enough to take a well-crafted campaign and engage with it on a superficial level. It is something else entirely to break apart the narrative that so many of these advertisements buy into. One of the critical impacts of corporate media is to shape and maintain our everyday perceptions and reinforce cultural norms. An exploitation of societal norms only serves to solidify issues such as our shocking drinking culture, double standards when it comes to sex, and our weakness for modern technology. A failure to challenge these norms is a failure to change them.

RTDs Baby

It is no secret that ready-to-drink beverages, commonly known as RTDs, are a bewitching alcoholic concoction for young drinkers. Promoters are careful not to breach legal standards in marketing them, but from an ethical standpoint a grey area exists. Sickly flavours such as passionfruit, raspberry, and whipped cupcake are lined up in perfect solidarity in bottle stores. Combine this with the associated taboo that makes alcohol “cool,” and it is foolish not to question what the target market of these drinks really is. It is quite ignorant to claim that young, or even underage drinkers are not drawn in by the charm of these cheap products with their brightly-labelled bottles and cans, which are easily consumed and therefore dangerous. Access to alcohol is not difficult for underage drinkers once an older friend or sibling or trusty fake ID becomes part of the equation. In a Select Committee address on the Alcohol Reform Bill late last year, Labour MP Maryan Street succinctly summed up the dangers of RTDs, dubbing them “the most flagrant attempt of the alcohol industry to lure young people by disguising what is otherwise the bitter flavour of alcohol, and an acquired taste, as a sweet drink.” Street essentially observed that youth drinking culture is not a matter of fine liquor appreciation à la Ron Burgundy but one of getting drunk for the sake of it and using alcohol as a vehicle for having a good time. The ability to “hook in” young drinkers is critical – thus the need for candy-coloured, saccharine beverages.Our culture has accepted alcohol as an effective social lubricant. It is easy to be drawn into the trap of accepting alcohol as just another ingredient to the recipe of having a choice time, bro. We applaud the ready consumption of alcohol, which is seen as the perfect antidote to our insecurities – in particular, the fear that our unaltered personalities are inadequate to interact with our peers.

One cannot ignore the power of targeted ad campaigns, from the rugged “Southern Man” of Speight’s to James Bond-wannabe Heineken drinkers. Although RTDs are usually advertised in print, it is valuable to consider how pivotal the packaging and point-of-sale displays are. The RTD is a class of product that trades on the existing climate of alcohol acceptance and, paradoxically, the taboo of alcohol – making it all the more exciting to younger drinkers. Thus the clichéd criticism of the sinful Vodka Cruiser, which is artificial and magnetically appealing to its baby-faced consumers. The Cruiser’s utterly offensive flavour offerings and unashamed tackiness is concerning in itself, let alone the way it fuels wider social problems.

What We Really Mean:

#lol #otp #wastey #yoloHouse of Durex

Durex ads have their ups and downs (you didn’t think you were going to escape reading this without a bad pun, surely?). Their flagship products do of course serve a useful purpose in preventing unwanted spawn and undesirable infections with highly unfortunate names. However, Durex is a brand and a business, offering more than just rubbers. The creatives employed to generate brand recognition play their cards in a risqué fashion. For example, an advertisement for a magical orgasm-inducing gel – even the astronauts can hear this lass coming thousands, if not hundreds of thousands of kilometers away. Screw intimacy and privacy and just let everyone know that you’re getting some, because everyone should be doing it. But you also need their product to truly enjoy yourself. Playing on the eternal fear of rejection – we are social creatures after all – Durex has astutely wrapped up its message into a relatively humorous ad. Their product is so out of this world, every girl will be a screamer.What We Really Mean:

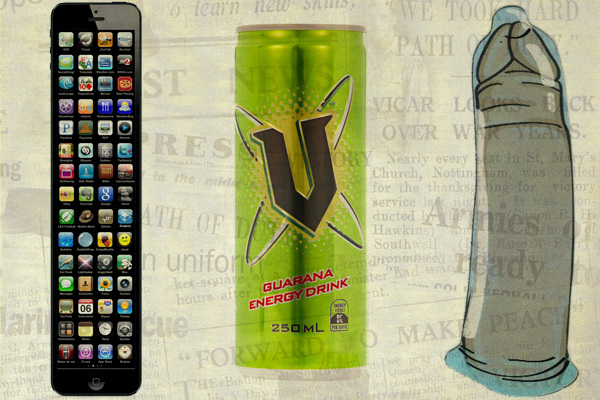

If you weren’t already uncomfortable with your body in an overly-sexualised world, now you can feel liberated as space(wo)men listen to your cries of delight – better than being a cat lady, right?The Apple Establishment

Apple’s simple design aesthetic carries through the brand’s entire range, from its products to its ad design, with succinct, catchy text and an appreciation of white space. This underpins campaigns dating right back to Apple’s inception, with an ongoing focus on the product as the pinnacle selling point: it is pitched in such a way that it “just sells itself.” However, it is not quite as simple as that.The tool for depicting an utterly fresh brand is a constant influx of new products, or at least, updated versions (hello, iPhone 5). Consumerist culture values the acquisition of stuff, which ties in perfectly with the minimalist print, web and television commercials thrust upon us. Apple constantly pushes “the new.” New ways of communicating with each other. New ideas. However, in Apple’s “effortless” cool, there is an overwhelming confidence in its constantly fresh products. The sweet irony is that when a new model enters the market, older models become somewhat less hip.

Our society values the use of technology, and rightly so – but to a degree. We instantaneously communicate and acquire new ideas with ease. This is certainly useful, but it is equally important to question the role of technology and its omnipresent existence in our lives. Apple relies on our fetish for groundbreaking technology and the perceived inherent value in its products to propagate its message, such as in the above web ad, which self-assuredly claims the latest model to be “the biggest thing to happen to iPhone since iPhone.”

Hidden beneath the clever copy is an outspoken confidence in the singular importance of the iPhone. Scared of losing touch with one another, we keenly buy into the Apple mantra (both literally and figuratively) at the expense of frequent face-to-face interactions. Actual interactions. Genuine interactions. So, tied up in Apple’s new product releases and irresistible brand image, there is in fact a crucial dependence on our love of technology and our fear of not having it and losing touch with one another. Despite the apparent simplicity in their brand offering, all is not what it seems. Question the Apple monolith and the dedicated worship of its holy offerings.

What We Really Mean:

If you want to be a real member of Western society in this technological age, the only way is Apple. It’s a really unique brand. Which is why everybody buys into it. We’re mainstream, but like, hip, you know?V: Poison of Choice

The V “Steal Your Share of $100k” pseudo-robbery operation is an elaborately executed campaign. Intricately played out but toying with an otherwise straightforward idea, it is a notable example of the kinds of interactive campaigns waging wars against each other in the 21st century consumerist jungle that constantly seeks to surprise and shock its targets. You can interact on the online platform by “stealing” money in the hope of winning actual money from the final prize pool. The project glamorously encourages people to unleash their inner crim – in line with a culture that accepts and normalises criminal behaviour – but with a carefully-worded disclaimer in the fine print to legally distance themselves from any mavericks who interpret their instructions too literally.Perhaps it is only a game, a cleverly fabricated battle in the competitive beverage world to project a message of V being illicit, cool and dangerous. Street posters include catchphrases such as “Rob thy neighbor,” a cheeky insult to traditional religious values to resonate with those oh-so-sinful non-religious types. One could argue it’s all just a bit of fun, that it is not that provocative, that we have seen worse. But over time, if companies continue to present content which pushes the envelope in a media-dense landscape, soon the once-controversial will become unremarkable, requiring even more provocative content to make a point.