What is Music?

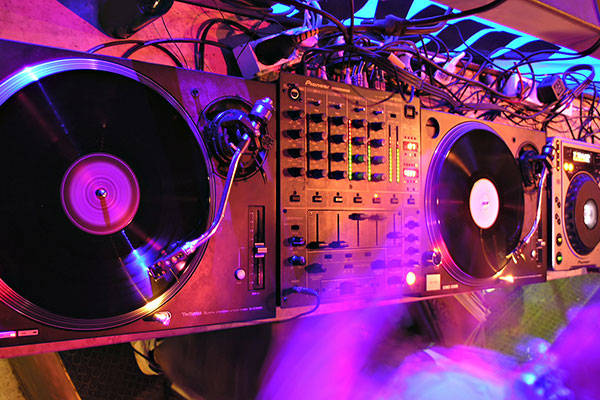

Because the canon of popular music has been losing its variation in song writing for a while, it has entrenched the idea of the ďproperĒ way a recorded song should sound to us: full, robotically perfect, loud. Statistically, music isnít just getting blander; itís all getting louder, a whole lot louder. That uniformity has led to the perception that no matter how amazing the song is, if it doesnít ďsoundĒ as good/clear/loud as another song, itís worse. There is an expectation, solidified by years of banal popular music, of how a song should sound or be recorded. This is fine, I can accept that. I admit that I am not enamoured with sound production in any way. Itís laborious and dreadfully boring, and for me itís just a means to an end so people can listen to my music without me being in the room playing for them. Even I have my limits, though. No matter what type of music it is, production needs to be accessible enough for people to enjoy the songs in the first place. For example, Daniel Johnston is one of my favourite songwriters of all time. He can be childish yet harrowingly sad and painfully accurate with simple technique and an eccentric voice, yet I can only listen to a few songs at a time due to the recordings being the musical equivalent of a person dragging the claws of a hissing cat down a chalkboard being played through a distortion pedal down the far end of tunnel as child pokes you in the face asking you if you are there yet when clearly you only just left the house. Itís the worst kind of torture. So I get it. But no matter how hard the recordings try to kick my soul in its balls, they are fantastic songs, in spite of the production. ďThe Story Of An ArtistĒ will always affect me immensely. But if Daniel Johnston wrote a club banger tomorrow, the recording quality would kill any chance of success. It would be a bad song in the mind of the masses. But if Rihanna sang the same song with David Guetta on a beach pretending to DJ even though his mixer is clearly not even plugged in, the kids would froth that shit.

I could perhaps accept that bad production should be equated to a bad song, but only if everyone who held that opinion had tried to record something themselves. When you hear a song live, you listen as much with your heart as you do with your ears. You feel the swell lift you up, tug you through emotions, and hold you on a string ó at least, you do if the artist is any good. When you hear a recorded song recorded, you listen less with your heart and more with your brain. And to create something that people listen to with their brains demands even more brains. Thereís not just one microphone in a room with a band. There is a microphone for every piece on the drum kit, two on the snare, up to four on just one amp and more microphones just sitting in the middle of the room. Itís crazy, and they still have to be mixed to sound good together, and thatís not even thinking about all the extra vocals, added guitars, kazoos, and the challenge of playing all of it correctly. Rihanna does it perfectly, but she can also afford to. Not every musician has her money or her team of production brains, but many of them have amazing songs, and nothing should take that away from them.