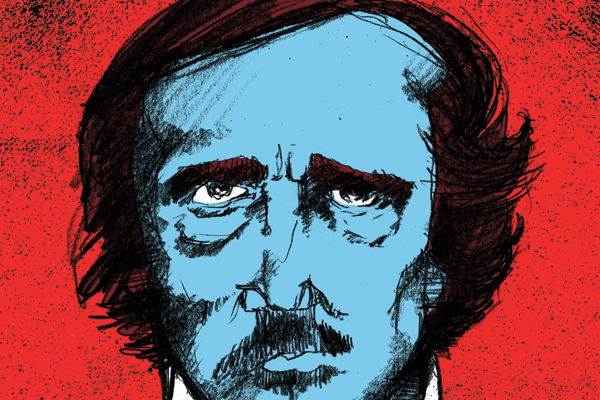

The original Goth

Dunedin’s children are the mildly unhappy descendants of a darker past. Goth is tempered, but not dead, and history has much to teach us. Had Lord Byron not exercised so much, perhaps he could have been the father of goth; instead, it is the famous Edgar Allen Poe, and his life holds inspiration and warnings for us all.

Poe’s melancholic mug was pale as Snow White’s, and framed with dark, softly curling locks; he even tried to straighten his hair, just like the darkly-inclined do today. His eyes were grey and “flashing,” and the popular images do not lie: his head was big, for it held many secrets: “His forehead was, without exception, the finest in its proportions and expression that we have ever seen.” The French poet Stéphane Mallarmé described his countenance as one any modern goth would be proud to have: Poe was “devil from head to toe! His tragic, black stylishness worried and discrete.”

Poe liked his colours dark, or preferably absent: he seems to have dressed invariably in black, except for a white shirt that peeped through the surrounding protective black layers. He was said to have sometimes worn a hat, and his clothes were beautifully cared for though well worn; he was never a wealthy man, “though his manner betrayed no consciousness of the fact”. Anyone wishing to emulate his style – the “romantic” goth – should consider a cravat, a small top hat, or, surprisingly, a Panama hat.

At home, he had a friend in what more spiritual goths might call a “familiar:” Catarina was a sweet, smart, tortoiseshell cat, and she shared a close connection with Poe. It’s said she would go into a “depression” whenever he went away, and to him she was something of a muse. He wrote often of “sagacious” black cats, which must have been witches in disguise; Catarina was never accused of this, but her clever antics helped Poe to describe the machinations of his fictional cats. Thankfully, the house-pet never endured the same awful fate as The Black Cat: she died two weeks after her owner’s death of what can only be imagined to be heartbreak (or starvation.)

At the heart of most modern goths is a tortured artist. Like many artists today, Poe dug out the harshest, most gut-wrenching inspiration when he was at his lowest. He wrote, with bleeding emotion and sympathetic insanity, heart-breaking and haunting poems and stories. Gothic literature existed before Poe, of course: Frankenstein, The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, and the lesser-known The Castle of Otranto, written by a man who went by the ridiculously un-goth name “Horace Walpole” are some examples. However, Poe went the extra mile and actually became a black-clad, ill-fated hope vacuum. His name is synonymous with horror and nightmares about ravens, but the dark subjects of his work and the fits of insanity his characters endured were often inspired by his own life.

When he was two, his mother died, and his father soon afterward. He and his siblings were split up and fostered, which, for Poe, meant a tumultuous relationship with his new father figure, John Allan. At eighteen he was heartbroken, trying to escape the military, and begging for more loans from his foster family. He dropped out of college, but managed to get Allan to fund a very small print run of Tamerlane and Other Poems, anonymously published and, like all good poems about ruined young love, inspired by the works of Lord Byron.

Tamerlane tells the tale of a great conqueror on his deathbed, lamenting the loss of his youthful love. It contains the beautifully bleak line: “And boyhood is a summer sun/Whose waning is the dreariest one,” alongside an angry adolescent challenge: “O, I defy thee, Hell, to show/On beds of fire that burn below/A humbler heart – a deeper woe.” These lines are completely stereotypical of the misunderstood, pained heart that lurks within every eyeliner-d scenester.

At the age of 27, Poe married his 13-year-old cousin Virginia, with whom he’d been living on and off. It wasn’t so unusual to marry his cousin, but the age difference did not abide by the classic “add seven to your age and halve it” rule, and they knew it: on the marriage certificate, Virginia is listed as twenty-one. Plenty of fears could ensue for Virginia’s safety here, but the reality is conjectured to be that she and Poe were close in a brother-sister kind of way. He nicknamed her “Sis,” after all. He’d lived with her family in the past, and after they married the two of them lived together with Virginia’s mother, Poe’s aunt. Some people believe Poe was never interested in sexual relationships, and some believe Virginia died a virgin, but friends of the couple said that the two slept separately until Virginia was 16, from which point they had a “normal” married life.

“Normal” insofar as a marital life plagued by flirtations and fans could be: we have enough problems with rumours and drama today; imagine how much worse that would be if you were in the midst of a losing battle with tuberculosis. A huge scandal suggesting improprieties by Poe, Osgood, and a woman called Elizabeth Ellet rose up to hound Virginia. Ellet, especially, was the bane of the married couple’s life: she worried Virginia and spread rumours that Edgar was “intemperate and subject to acts of lunacy”. In a pathetic act worthy of most second-year students, she labelled Poe an alcoholic. On her deathbed, Virginia allegedly said it wasn’t just the TB that got to her in the end: “Mrs E. had been her murderer.”

He had now lost both parents, his brother, his foster mother, and his wife to tuberculosis. The disease haunted many people in the 19th Century, and while those who contracted it had a habit of dying horrible deaths (a lethal stage of the infection involves death by drowning in your blood-filled lungs), the pallid skin, rattling breaths, and flecks of blood in the breath are all horror description staples. The disease was tragic, and could make for a grim writing prompt.

Scattered among these deaths were intense romances with beautiful women ripped away from him by fate, parents, or marriages. It is no surprise, then, that the loss of female figures in his life heavily impacted his writing: Poe believed there was nothing worse than “the death of a beautiful woman,” which is possibly why he wrote about it all the time. When a character had to be morose, bereft, or otherwise blue, it was these heartaches he drew on to portray emotion.

The angriest of his emotions were brought out by his career competition: like any good historical character or rap star, Poe had a nemesis. Rufus Griswold had a rough-sounding name and an even gruffer personality. He managed to match Poe in a lifelong despondency, if not literary ability: he described himself at 15 as a “solitary soul, wandering through the world, a homeless, joyless outcast”.

Both members of the publishing world, Griswold asked if Poe would give him something to put in The Poets and Poetry of America, a well-respected anthology. When it was published and Poe saw that he was shoved into the back of the book, which was filled with works he deemed inadequate, he wrote a scathing criticism of it. Wherever they toured, they threw massive shade at each other. Griswold succeeded Poe as editor of Graham’s Magazine, and they both vied for the attentions of the writer Frances Sargent Osgood, which Poe won. Though stressful, none of those competitions seem reason enough to launch a posthumous smear campaign, which is exactly what Griswold did.

It began with Poe’s obituary, written by Griswold under a pseudonym and containing such snarky phrases as “This announcement will startle many, but few will be grieved by it.” Griswold somehow became Poe’s literary executor, and wrote a biography painting him as drug-addled and mad; it became the popular view of Poe, despite the claims being untrue. Interestingly, when Griswold died eight years later, the three portraits in his room were of himself, Osgood, and Poe.

The dark and deranged image of Poe caught on, just as the “mad, bad, and dangerous to know” Byron had; but it’s not quite the truth. Poe had a tragic life, and certainly wrote on deranged topics, but he was not mad; nor was he bad. Like every other person who’s been a picture on a T-shirt, there is much more to his life than was thought; and it’s all even more sadly goth than we thought.

Poe had to have a vice; he was surrounded by death, prone to sadness, and spent long periods being a full-time author of the macabre. He chose the tried-and-true destructive escapism of alcoholism. Slander spread by his nemesis Rufus Griswold after his death painted him as drug-addled, and accused him of abusing laudanum (“tincture of opium”); there is no evidence that he ever took drugs outside of alcohol. Although it is still popularly believed he was into opiates, most experts put this down to people confusing Poe with his fictitious narrators.

Ellet was right about his drinking, though: alcohol was his vice. Guillaume Apollinaire called him “the marvellous drunk from Baltimore,” but others could see that his drunkenness was anything but marvellous. Charles Baudelaire was the main translator of Poe’s works, and a big fan. Even he could see that the drink was a symptom of Poe’s depression and not a quirky character trait: “literary jealousies, the vertigo of the infinite, marital woes, the insults of poverty: Poe fled all of it in the darkness of his drunken stupor, as if in the darkness of the grave.” We can all relate to enduring “the vertigo of the infinite,” but we must watch our binge drinking, and ask ourselves from time to time: would this be better dealt with by writing a poem?

At the age of 40, he finally became engaged to his childhood sweetheart Elmira Royster, who he thought he’d lost when he went away to college. He joined the Sons of Temperance, a kind of 19th-century Alcoholics Anonymous, and looked to be entering a happy spell. Months later, he was found deliriously wandering through Baltimore “in great distress” and wearing someone else’s clothes. He died a few nights later, repeatedly calling out the name “Reynolds.” The cause of death is unknown, and his death certificate has been lost.

Not all of Poe’s fans have been goth-sympathisers; among the day-walkers was a young Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of Sherlock Holmes. Holmes is consistently listed as one of the greatest fictional characters of all time: he is a mix of inductive-intelligence, a passion for the outlandish, and drug dependence. Despite his positives, he is also an arrogant asshat. Holmes spends his stories trapped in a structure of victim-meeting, plan-presenting, and then smugly masturbating his own ego as a conclusion, all while criticizing his best friend and personal physician. To make Holmes a sympathetic character, it could be as simple as having him explain his deductions through rational argument instead of magically making miniscule observations then picking the right cause out of a hat. However, if Conan Doyle had done that he would be very close to plagiarising Poe. Conan Doyle believed that Poe had invented the detective genre, and I believe that every crap part of Holmes is just a mistake made by poorly copying Poe’s perfect detective, C. Auguste Dupin.

As the astute reader will have guessed, Dupin was a goth who fought crime. He and our narrator take long walks at night, board up windows, smoke indoors, and commit minor extortion. They first appear in The Murders in the Rue Morgue, in which Dupin sets a trap for the owner of a murderous Orangutan, and continue to deduce themselves money and smugness in The Purloined Letter and The Mystery of Marie Rogêt, all before the invention of the word “detective.”

It was The Mystery of Marie Rogêt that demonstrated Poe’s abilities as a deductive genius, not just a literary one. The body of a girl called Mary Rogers was found floating in the Hudson River, and the newspapers went into a frenzy. Using all the information available to the public, Poe wrote Marie Rogêt as an exercise in mystery solving. Poe’s story is set in Paris, but otherwise has the same details as the real murder case. Dupin’s reasoning, which Poe of course shares, leads him to the correct answer. Poe didn’t just create the deductive detective; he was one. Other authors fictionalized the murders, but only Poe solved the mystery; he was right.

In an exciting twist, truth proved far less interesting than fiction: Marie Rogêt was a critical failure. One critic describes the story’s inability to captivate thusly: “Only a professional student of analytics or an inveterate devotee of criminology can read it with any degree of unfeigned interest.” There is no story, just an information-dump and a series of deductions. Interestingly, this is the exact formula used in the Sherlock Holmes stories, although in Conan Doyle’s version the audience is bereft of half the information until the end.

Poe’s legacy is one to interest and inspire members of subcultures – goth and beyond. Today’s popular image of him is a haunted, mustachio-d ravenophile, who took drugs and cried too much; a very relatable character. Perhaps if he could have taken his own selfies, like us, we would know his true beauty. In reality, his vast, subject-spanning intelligence and groovy style got him plenty of party invites: Poe was just like you! His works and lifestyle contain something for everyone: the writer; the criminologist; the fashionista; the AA group leader; and the butterfly emerging from an emo cocoon.

Your boyhood is waning, and adulthood threatens to rip the value from your carefully cultivated sleek black bangs. You can keep them, though, if you go Poe. Go to parties, little goth, and drink your woes away; if you write pretty enough words about it, history will forgive you. Take a logic class, and enjoy Marie Rogêt. Invest in staple items you’ll wear to your grave, and get a pet that will go to it with you.