Despite the difficulties that the queer community continues to face, society overall has come along way in its treatment of homosexuals. However, there is a final burden to overcome, a final group still pushed to the margins and ignored, still treated with a level of disrespect that we would consider unconscionable; this is the world of the transgendered.

Transphobia seems to be one of the last acceptable taboos in western culture. Children that do not conform to their biological gender are over 40% more likely to experience childhood abuse; their lives are likely to be are plagued by discrimination, barriers to health services, and limited legal and public recognition of who they really are. They are blocked from enjoying the same rights and responsibilities as everyone else. Zane Pocock looks into the lives of the transgendered, and the struggles that they face.

Trans-NZ

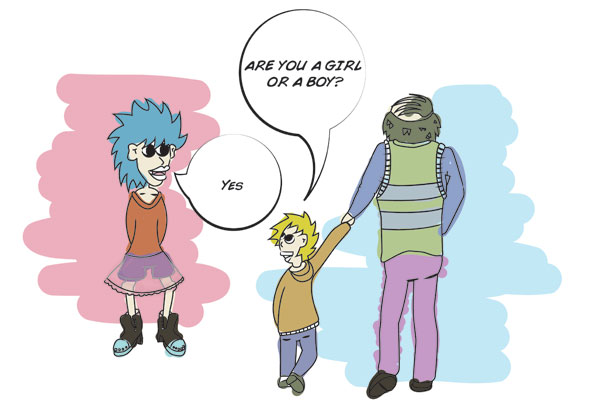

Transgendered people are those who innately identify with a different gender to their biological sex. Most “cis” individuals (those who align with the gender they were assigned at birth) are ignorant of what it is like to live as a transgendered person, or of the immense challenges they face every day: Transitioning or living as a trans person can be immensely difficult. Jamie Burford, queer/trans activist and former OUSA Queer Support coordinator at the University of Otago, says that, “of all the students I worked with, the trans-identifying or gender-questioning students often had the roughest time.” This takes the form of challenges around access to healthcare, being able to have their gender identity recorded by the University, or simply being able to find a bathroom to use safely on campus.Because some trans people may not “pass” easily as the gender they identify with, they can “bear the brunt of the worst violence and verbal abuse,” Jamie says: “There have been times when we’ve had to take complaints to the Proctor because trans people have been walking around the campus area and have had abuse hurled at them: ‘What is it? Is it a boy? Is it an it? Is it a girl?’ – that kind of stuff. I remember one student who didn’t even feel safe enough to go back and collect his car at the end of the day.”

The University seems to be trying to make changes for trans students at Otago: Recently, there was a successful request to get preferred gender listed on University documentation. “But it’s a difficult, exposing process,” says Jamie. “It’s not just an opt-in. Students are having to do this work on top of their school work, on top of the work of possibly getting hormones, possibly contemplating surgeries and probably talking to their family, friends, partners, and employers about it. It’s a lot of work.”

As a result of transphobia, trans people experience a higher number of negative indicators for health and wellbeing, including higher rates of rape and sexual assault than cis-people, drug and alcohol dependencies, and poor educational outcomes. “Many trans people struggle to get the care, services and support they are entitled to,” Jamie concludes, but “most trans people are strong, amazing and awesome in spite of it.”

Transgendered people are those who innately identify with a different gender to their biological sex. Most “cis” individuals (those who align with the gender they were assigned at birth) are ignorant of what it is like to live as a transgendered person, or of the immense challenges they face every day: Transitioning or living as a trans person can be immensely difficult. Jamie Burford, queer/trans activist and former OUSA Queer Support coordinator at the University of Otago, says that, “of all the students I worked with, the trans-identifying or gender-questioning students often had the roughest time.” This takes the form of challenges around access to healthcare, being able to have their gender identity recorded by the University, or simply being able to find a bathroom to use safely on campus.

Because some trans people may not “pass” easily as the gender they identify with, they can “bear the brunt of the worst violence and verbal abuse,” Jamie says: “There have been times when we’ve had to take complaints to the Proctor because trans people have been walking around the campus area and have had abuse hurled at them: ‘What is it? Is it a boy? Is it an it? Is it a girl?’ – that kind of stuff. I remember one student who didn’t even feel safe enough to go back and collect his car at the end of the day.”

The University seems to be trying to make changes for trans students at Otago: Recently, there was a successful request to get preferred gender listed on University documentation. “But it’s a difficult, exposing process,” says Jamie. “It’s not just an opt-in. Students are having to do this work on top of their school work, on top of the work of possibly getting hormones, possibly contemplating surgeries and probably talking to their family, friends, partners, and employers about it. It’s a lot of work.”

As a result of transphobia, trans people experience a higher number of negative indicators for health and wellbeing, including higher rates of rape and sexual assault than cis-people, drug and alcohol dependencies, and poor educational outcomes. “Many trans people struggle to get the care, services and support they are entitled to,” Jamie concludes, but “most trans people are strong, amazing and awesome in spite of it.”

Trans what?

Being trans-gendered basically means moving from one gendered space to another. There are lots of terms and it can be difficult to get your head around them all. As Jamie puts it, “we have the word trans*, which is often used as an umbrella term for lots of identities such as gender queer, trans-gender, trans-sexual, fa’afafine, and other kinds of culturally specific ways of being ‘trans’. Some people may just identify as trans, but we can also use trans* as the gender-diverse composite term.” The two main terms to know are “trans-man” – a man who was assigned female at birth – and “trans-woman” – a woman who was assigned male at birth. Jamie himself identifies as gender queer: “Obviously I haven’t transitioned from male to female, but I exist in a realm somewhere between those two genders.”It is important not to make assumptions about trans people: They may or may not decide to take hormones, or have surgeries performed. They may be gay, straight, bi or any other sexual orientation. They might be out, or they might not be. The complexity of each individual’s situation means that the easiest way to know for sure is simply to ask.

Interestingly, Jamie wants us to “think about cis-sexism, as opposed to transphobia. While cis-sexism might be a new word for some people, it is perhaps a more accurate reflection of the systematic de-valuing of trans* folks (in the same way sexism devalues women – we don’t call sexists woman-phobic) – whereas transphobia minimises the structural element of this kind of bigotry, instead focusing on the so-called ‘phobia’ of the individual.”

Whether you call it cis-sexism or transphobia, Neill Ballantyne, the current OUSA Queer Support coordinator, thinks he can understand the reasoning behind it. “Initially, being trans is obviously quite hard to understand for cis individuals because they don’t feel that way – so they think, well, ‘why would you go down that track?’ But I think it’s also quite challenging to our society’s stereotypes and norms around gender in general. So as you’re aware, with media, societies traditionally perpetuate stereotypes around the butch manly man and the fairly docile, submissive woman.

“So media and advertising have got this very polarised idea of gender. And trans-gender completely leaps all of that, because you’re born a man but you want to become a woman, or you feel that you identify as a woman, and then that whole gender thing starts becoming less like boxes and more of a fluid spectrum that can sort of flip as well. So I think people find it challenging, hard to understand, and it can be quite confronting for people as well, as they sort of go ‘well, what’s my gender?’”

Recently, it seems trans issues have struggled to receive the limelight, especially compared to the experience of gays/lesbians. “Trans people haven’t emerged on our TV screens in the same way. It’s not as visible. Lots of people don’t realise that there are trans people walking around this campus,” Jamie remarks.

It should be easier

I caught up with Andrew (not his real name), a third year Otago medical student who identifies as transgendered. Andrew was assigned male at birth, but wants to transition to life as a woman. At the moment, he is fine using male pronouns. “For me, being transgendered is weird, because I’ve been taught to be a guy for 20 years. I went to an all-guys boarding school, for example. But basically from when I was 12, I’ve felt like I wished I was a girl.”Since his early teenage years, Andrew would lay in bed at night, wishing he’d wake up female. “But it was a fantasy. That’s what I thought: I’m a guy. I’m not allowed to be a girl. It doesn’t work that way. In my mind I just told myself ‘be realistic and be a guy’.”

Interestingly, it wasn’t until university that he got the courage to experiment, but that experience quickly turned sour. “When I first started it was pretty positive. I was like ‘Oh my goodness, I may be able to look like a girl!’ and I had hope that this may just work. But when you’re coming out in public, people close to you are the hardest. I had friends at UniCol who I thought were quite open-minded. But the first time I was cross-dressing in front of them, one girl just cracked up laughing and couldn’t stop. Another guy was like ‘I’m totally fine with it, but just don’t do it in front of me.’ But that’s not tolerance, you know?”

This makes it difficult to choose whom you tell about it. Andrew has told a lot of people – even his parents – but as for showing them pictures, or dressing as a girl in front of them, “I haven’t had the courage. People can say they’re really supportive of what you’re doing, then just shut off once they see you as a girl.” Andrew thinks it’s difficult for friends who know him as a guy to suddenly be confronted by “BAM! I’m wearing a dress! They don’t know what to say or even think.” He does, however, find girls in general to be a lot more accepting.

As for coming out of the closet completely, well, that’s yet another challenge. He’s trying, but “it’s not as easy: I’m not a naturally extroverted person. Some trans people just don’t give a shit, and I’m jealous of that. For me, it’s about taking small steps – three steps forward and two steps back. I hope to be completely out and be able to live as a girl every day at some stage, but it’s hard to see exactly when that’ll happen or the best way to go about doing it.”

It can be very difficult for trans people to realise their goal of physical transition. Andrew would love to have genital reconstruction surgery, “because I don’t see myself getting intimate with anyone else as a guy.” Having this surgery in New Zealand is difficult due to long waiting lists in the public health system, and it’s a huge sum of money to undertake surgery privately. Still, this is a route taken by many.

There are a few resources for trans people, but not many in Dunedin. Although OUSA’s Queer Support do a really good job running SPACE on Tuesdays – which is basically just a safe place for people to talk – there are no specific trans groups in Dunedin. UniQ is a great place to go, but the purpose of it is to socialise and mainly meet gay guys/girls, which isn’t necessarily what a trans person wants.

Rather than physical violence, Andrew identifies social awareness and acceptance as the biggest challenge. “It’s just the general attitude that is really crap,” he says. “Being gay, when you come out people don’t really need to know, but when you come out as trans, especially those who don’t pass as the opposite gender well, you feel like you’re wearing a giant badge asking to be abused.”

In 2008, the NZ Human Rights Commission published a report entitled “To Be Who I Am”. The report recommended four areas for immediate attention: Increasing participation of trans people in decisions that affect them, strengthening the legal protections making discrimination against trans people unlawful, improving access to health services, including gender reassignment services, and simplifying requirements for change of sex on a birth certificate, passport and other documents. This report is a stepping-stone in ending discrimination against trans people.

One of the most striking things Andrew says is that “even some gay guys get a little freaked out, which is really disheartening.” This mistreatment within the wider LGBT community is, in fact, well recognised. As Jamie says, “I think that the wider queer community needs to take some responsibility for that. Often GLB people aren’t good at standing alongside trans people. There’s an unfortunate history of that too, of trannies being the weirdos on the fringe. And middle-class white gays and lesbians going like, ‘ooh that’s a bit intense for us; we just want to be seen as normal.’

“So I think there’s some wider responsibility there from the wider queer community to step up and advocate for trans folks. Because there’s lots of queer people who are ‘yup, as soon as we get marriage and adoptions, we’re sorted’ – forgetting the experience of trans people altogether. So I think not only are trans people marginalised within wider society, they’re also marginalised within GLB(t) communities. The T is often a silent T, a very small T. I think that makes it doubly hard.”

It’s so bad that there was even a report published by the American National Center for Transgender Equality in 2008 on “nine keys to making lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender organisations fully transgender-inclusive”, entitled Opening the Door to the Inclusion of Transgender People.

CIS-ADVICE

Jamie says that cis-gendered people should treat transsexual people exactly as you do with any other. Take cues from their presentation: How people present themselves is generally a pretty good indication of the pronoun (“he” or “she”) they want you to use. “If you’re in doubt, ask the person in the most private, discrete and sensitive way possible,” says Jamie. “But in most cases that won’t be necessary. What it’s not okay to do is purposefully mis-gender a trans person – referring to their biological sex, name, pronoun, any of that stuff. That’s just not okay. Many trans people are really generous, and will be okay with people making mistakes. So don’t be afraid, but be sensitive and try to get it right.” Being transgendered is a small part of who these people are, it’s not an exhaustive definition. What they want is no different to what we all want: Respectand dignity.

As a middle-class, straight, cis, white guy, I was accepted with open arms by the queer/trans community while researching this article. It’s high time that cis-heteros repaid the favour. With recent reports on the experiences of transgendered people, the framework for positive change is definitely there. Transgendered people are already working hard to realise their rights, often without the support of others. To cure transphobia/cis-sexism, the challenge is for the rest of us to step up to the plate and challenge our own assumptions about gender – the problem is not with the trans people, it is with society’s inability to accommodate, accept and celebrate them.