Why do we, Critic Te Ārohi, release this annual te reo Māori issue, the one that you now hold in your hands? The surface-level answer is simple: because it is Māori Language Week, September 12-19th.

Well, yes. But why is Te Wiki o Te Reo Māori marked out to be these specific dates and not anywhere else on our Gregorian calendars? The answer rests within a wider context of events, which not everyone in Aotearoa (honestly, until very recently, myself included) is entirely aware of. On September 14th 1972, Te Petihana Te Reo Māori was delivered to Parliament by a large hikoi of Māori kaumatua and activists. It was a petition more than 30,000 had signed, calling for the active recognition of te reo Māori by the government in this country, 130 years after the Treaty of Waitangi was signed. It read as follows:

“We the undersigned, do humbly pray that courses in Māori language and aspects of Māori culture be offered in all those schools with large Māori rolls and that these same courses be offered as a gift to the Pākehā from the Māori in all other New Zealand schools as a positive effort to promote a more meaningful concept of integration.”

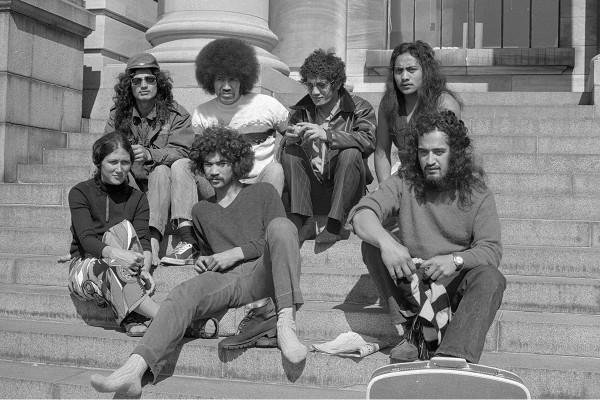

Seems simple enough, right? Not too much to ask for? This petition was the culmination of a mass movement in the shift of mindsets for Māori. The Māori Renaissance Movement, with its lead activist group Ngā Tamatoa (The Warriors), included some notable names such as Tame Iti, and Rewi Paratene – current Greens co-leader Marama Davidson’s father – and they strongly advocated for Māori liberation. This shift was driven by a Māori consensus that the settler government had failed to deliver on the premises of Te Tiriti in virtually all areas.

The ‘link system’ - the teaching of te reo Māori at primary and secondary schools - was incorporated into the curriculum under the administration of Labour Minister of Education at the time, Phil Amos. Beforehand, the speaking of te reo Māori in schools had been discouraged; physical punishment had even been handed out as consequence. The Native Schools Act 1867 had made it official government policy to teach only English wherever possible. Many older Māori today, including former Minister for Development Dover Samuels, can still recall being “beaten until [they] bled” at school just for speaking te reo.

With further support and with the actions of the Ngā Tamatoa activist group, Māori Language Day was introduced in 1975. It came on the anniversary of the day the petition had been delivered to Parliament, and eventually was extended to encompass a whole week for celebrations.

A decade later in 1982, the first Kōhanga Reo (pre-school) was opened at Wainuiomata (Wellington). At the forefront of the Kōhanga Reo initiatives was te reo Māori. In creating a space early on in Māori children’s lives for full immersion, it was hoped that this would revitalise the struggling language, and thus, the strength of the culture itself. This idea, referenced in Kaupapa Māori Theory – an approach to Māori education through immersion in te reo Māori - echoes the calls of Paulo Freire, who argued that the oppressed must be the proprietors of their own liberation; to expect the gift of liberation at the hand of the oppressor is to be considered a contradiction in one’s search to gain true freedom.

The fact that the Kōhanga Reo initiative was community-instigated, and followed a mindset shift for Māori, highlights the incredible mana and resistance of Māori against the unfathomable odds of oppression. A critical understanding and a self-emancipation-focused political consciousness resolved in Māori taking action within their own lives, founding the new era of cultural revival for Māori – one that we’re lucky enough to live in today.

How should we expect all this to be common knowledge when our education system is built entirely on the values of Western Imperialism, a European school of thought that was the basis of the Western colonial agenda? Well, that falls to us. Because if you didn’t know the origin of Te Wiki o Te Reo Māori, well, e hoa, now you do. Talk about it. Share its story around the dinner table next time you visit whānau. Educate them. Continue the mahi that started fifty years ago, and celebrate the victories of our tūpuna. Uphold the mana of our reo. Kia ora.