Asleep: The Forgotten Epidemic That Remains One of Medicine's Greatest Mysteries

Written by Molly Cadwell Crosby

Probably because that would require talking about it, and talking about it would require thinking about it. People donít want to do that. Because this disease is terrifying.

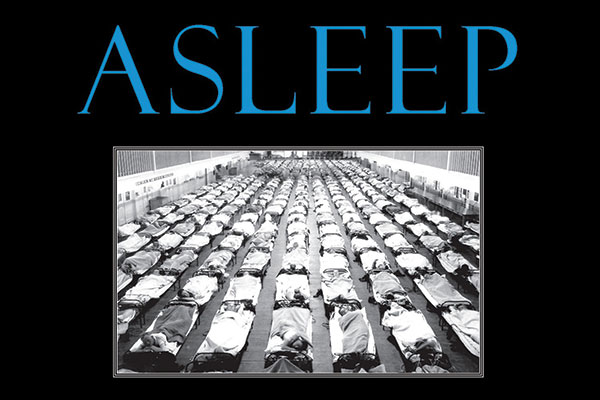

It was colloquially known as sleeping sickness because the most famous cases often involved people staying asleep for months before dying, but some who suffered from encephalitis lethargica instead lost the ability to sleep at all, which can kill you and did kill them. The symptoms varied wildly from person to person. People who survived the initial outbreak would often alter dramatically in personality, to the point of seeming like different, and much less pleasant, people. In particular, children who had seemingly recovered would lose all control of their impulses when going through puberty, becoming so dangerously violent that it was considered necessary to isolate them from society.

Since they donít really know what caused it (the accepted answer is ďsomething something flu somethingĒ) they donít really know why it went away. It could come back as an epidemic, cases do still occur occasionally, and there isnít a cure. You may now understand why the usual reaction to this disease is to just avoiding thinking about it.

Asleep takes case studies of seven patients and combines them with a focus on the physicians who studied encephalitis lethargica. Probably the most frustrating thing with the book is a result of what makes it so frightening: itís all true. Crosby has to work with what was recorded and, sadly, people at the time werenít especially invested in keeping track of those who suffered from this disease. The case histories Crosby presents have a tendency to vague out into question marks once the subjects are no longer receiving medical care. This works as a pretty excellent allegory for how the medical world as a whole treated encephalitis lethargica. Unfortunately for most, this results in a book that is in no way suited to people who like closure or happiness.

However, if you are like me, morbid and attracted to any information you can use for disturbing anecdote fodder at parties, read Asleep. Have nightmares.