“People piss themselves, shit themselves,” says Rory Foley casually as he shows us through the empty prison. Foley delights in terrorising people, for charity.

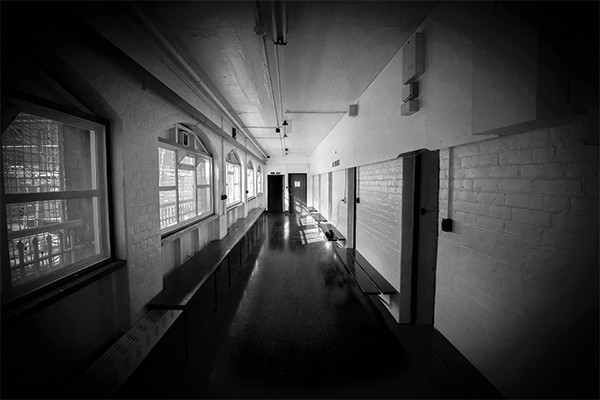

It’s a grim place to walk around. The Dunedin Prison was completed in 1896 and used for over a century until its closure in 2007. The old prison cells are worse than I imagined they would be. The old beds are tiny. I look up at Matt McKay, our photographer, who is tall. He reckons he could just fit on the bed if he curled up. Foley says the toilets were installed in the 2000s. “Before that, they used a bucket. There was a real rotting flesh smell.” He tells us that the barred windows along the length of the building used to have no glass, so the freezing Dunedin air could blow straight in. The only light was from small gas lamps embedded in the walls between the rooms.

While we were visiting, the prison was being set up as a haunted house. Fear NZ is New Zealand’s biggest horror charity company. They go to traditionally scary locations - empty hospitals, prisons, and warehouses – and set up an immersive experience to literally scare the living shit out of people. The company sets up scenes in the chosen setting and employs actors to dress up as terrifying characters. Foley says there are two “so-called nasties” (ghosts) floating round the prison. I asked what they do, and he said, “annoy me”.

Foley started Fear NZ despite being told it wouldn’t work out. He was working in North America when a friend suggested they go to a haunted maise maze. He got chased by a guy with a chainsaw and had a blast. When he got back to South Canterbury, he decided he wanted to make his own haunted experience. “Everyone said no, it won’t work. I decided to do it anyway.” He cut all the tracks by himself, created a Facebook page with a friend, and put up some posters. They had seven actors and only had masks for them to wear - no costumes. They had one chainsaw. Foley took bookings on his cell phone. The first weekend sold out, then the second weekend, and then the third. They donated the proceeds to the Cancer Society, which helped get people on board. Then a school asked if they could set up in an old hospital. “Now we have around a hundred people on our booking staff; we’re all over NZ; we’re considered the biggest and best to be dealing with now.”

The team design the experience to fit the space. No two set ups are the same. “I have to keep walking through to get the flow right.” Foley says he’ll start by going through what was in his head, but will often realise it’s not going to work because of how the scares are going to happen. “We want to stagger them. We don’t want the adrenaline to plateau; we want it to peak over and over again.”

Critic sent reporter Chelle Fitzgerald to Fear NZ. The first thing she was made to do was sign a liability waiver and say she was not pregnant, did not suffer from epilepsy, heart conditions or high blood pressure, and wasn’t under the influence of alcohol or drugs (she says, “I possibly might have lied, but what’s a bottle or two of wine anyhow”).

Chelle was accosted by the most intimidating mad she’d ever seen. “He was at least seven feet tall, muscular, broad and had a prosthetic skeleton face.” He got right up in her face and told her to “hurry the fuck up and get going through a door”. Strobe lights started flashing and “a motherfucking dude came sprinting at us with a goddamn running chainsaw. Fuck me sideways. I didn’t even realise I had a fear of chainsaws before this ordeal.”

Later, Chelle was shoved into a black cell and the door was locked behind her. She sensed a “presence in the room,” and felt uneasy and claustrophobic. Then something happened – a shuffle, coming from the corner of the cell. “Fuck. It came at me, illuminating itself only enough for me to see its general shape. I still don’t know what that fucking thing was but it screeched at me and I started pounding on the cell door. I was let out, and a clown followed me, breathing down my neck.”

In the US, extreme haunted houses are getting more and more daring as the demand for them grows. Blackout Haunted House makes patrons suck on bloody tampons and occasionally does faux-waterboarding. Dead of Night in Long Island zips people up in body bags. Scarehouse: The Basement in Pennsylvania gives electric shocks. The Cult in New Hampshire lets cockroaches loose on people’s bodies.

McKamey Manor is a nonprofit haunted house located in Russ McKamey's backyard in San Diego, California. Guests there are put through possibly the worst (consensual) torment of any haunted house in the country. They give the patrons unwanted haircuts, drench them in fake blood, submerge them in water, force them to eat and drink unknown substances, and even bind, gag, and drug guests in order to induce hallucinations. The house permits just a handful of patrons every weekend. They used to accept payment only in the form of dog food, but now they take donations to the local dog shelter. The tour can last anywhere from 4 to 8 hours, and nobody has made it all the way through, despite there being no safe word. There is a waiting list of around 20,000 people.

Foley told me that in New Zealand they can’t go anywhere near what America does, “in terms of nudity, the forced feeding, or even the sexual insults and things like that. We can’t do that kind of stuff, legally and morally.” He says that even if they could do those things, our population is too small for there to be enough demand for it. Only a small percentage of people have any interest in an experience like McKamey Manor. Foley and his team try to make sure their patrons get a really good scare, but they don’t want them too traumatised to ever come back. He gives the example of a haunted house in America where they do military-style torture. “They put bags over people’s heads and then send them into a room where there is a continuous siren playing for ten, twenty minutes. It’d just drive you nuts.” They’ll drench people in water, chuck them in a river, and pour pigs’ blood over them. “We can’t even do that. We can’t even use pigs’ blood because it’s a health and safety issue. We have to make fake blood.” He sounded a bit annoyed. “We’re looking into smells, but there are some people who react to smells, just like there are people who react to strobes. We have the odd vomiter. People faint. We had a guy faint last year.”

They try to make the scares completely different at each location. “A military asylum is different to a prison.” The waiver that patrons have to sign says that the actors can touch them, but they can’t touch the actors. “If you touch us, you soon find out why you don't.” Patrons can put their hands up to communicate they’re not enjoying this part of the experience, but they wish to continue. The safe word is "purple". As soon as an actor hears the word “purple” they break character and immediately make contact with the person, then get them to a security person who will see them out.

Foley says that different people react differently to different things. “Some people are very scared of the darkness, confined spaces. A lot of people will just freak out when the door clangs [prison doors are loud] - you imagine that with the strobe lights going and us walking round. We have a whole population of clowns.” They also play music, made by Foley, with a tempo slightly above a human heartbeat.

A session with Fear NZ takes around 15-20 minutes, depending how long people last. Chelle lasted about 20. At one point she found herself in a derelict hallway full of “neglected insane patients. They were horrific and some had open wounds and looked to have escaped the operating table mid-surgery.” At the end of that hallway, there was a psychotic surgeon performing surgery on a screaming patient on a filthy gurney.

Moving through, she was grabbed by soldiers and told harshly to stand against the wall, before being sent into a pitch-black corridor. “In there we were accosted by all sorts of fucked up creatures who wanted to touch.”

She finally made it out, heart pounding, to be farewelled by a friendly staff member and the St John ambulance staff. She gave the experience, “18/10, highly recommended”.

The St John staff are there in case someone gets into a dangerous state, like a heart attack. One of the charities Fear NZ raises money for is the New Zealand Heart Foundation. I asked Foley if anyone had ever had a heart attack while inside one of his haunted houses, and he said, “not yet”.