Once upon a time, the great being Mata Nui wandered the endless cosmos. But his evil brother, Makuta, plotted to destroy him. Makuta summoned hoards of monsters, but could not take the Great Spirit’s life. Instead, Makuta cast Mata Nui into an eternal slumber. His body came crashing down from the heavens into the sea, forming our pristine world. The first people were villagers called the Tohunga, performers of the Great Haka, children of Rangi and Papu, and they lived in peace with their environment. But trouble is stirring in Mata Nui. Prophecy has foretold the coming of a new Toa, and the forces of Makuta will stop at nothing to control him.

Sound familiar? That’s probably because most of those names and words come directly from te reo Māori. But this isn’t a traditional pūrākau (legend). This is the plot of Bionicle, a line of toys made by the LEGO Group.

I wanted to write a piece about appropriation of Polynesian culture by a Danish toy company, but this quickly spiralled out of control. Turns out, Bionicle isn’t just a toy brand with a loose veneer of Polynesian culture; it has a ten-year history spanning an astonishing 2,000 pages of lore — plus video games, comic books and movies. This lore is so dense and incomprehensible that we had to get one of our volunteers to watch a nine-hour-long video on the backstory, coupled with an 83-page treatise on their language and a bona fide academic paper from the University of Copenhagen to boot.

2001 saw the release of Lord of the Rings, a movie based on a book based on one man’s obsession with creating a language. It also saw the release of Bionicle, a toy line based on one man’s severe illness and flavoured by Polynesian culture, and also centred on a language. I am not exaggerating when I say these two fandoms have comparable troves of background lore, which is why we are explicitly sticking to the 2001-2003 period of Bionicle, from the first release of toys, to the first movie.

Simply put, the basic idea of Bionicle (read: Biological-Chronicle) is that a big robot crashes down because the cells in his body are fighting for control. He goes to sleep in the ocean and the parts of his body above water become islands (sound familiar?). Unbeknownst to the inhabitants, their entire existence is within a larger being, where they must fight off “infections” in the form of the Makuta to save the host body. The canisters the toys come in are even shaped like pill capsules. That’s the “Biological” half.

To build the “Chronicle” half, creators of Bionicle tapped into genuine island culture for “inspiration”. Here is one of many, many examples: most of the Tohunga (villagers of the Matoran species) are on Mata Nui (the main island). They live in six different wahi (biomes), and if they are given the chance to take up a Kanohi mask, they can unlock their elemental powers and become a legendary Toa warrior. Once a Toa feels their duty has been fulfilled, they can transform back into a villager, except this time they’re a wise elder. Every single one of those terms is a direct translation from te reo, except ‘Matoran’.

In 2001, LEGO had just bought the rights to Harry Potter and Star Wars, and while their toys were a hit, their finances were in the shit. Bionicle was there to save the day. Propped up by rich Polynesian history and language, the product line was the only profitable LEGO product for several years, single-handedly keeping the entire company above water. Part of this success was the toys themselves (fuckin’ ripped), but part of it was also due to the vast world imagined by the product line’s designers. This lore was clearly inspired by te ao Māori and other Pacific islands like Fiji and Hawai’i. All this backstory had already been set up when LEGO started releasing the toys and online game, and while Western audiences might’ve thought of it as “cool, exotic nonsense”, a lot of the terms started to seem very familiar to people in Polynesia. Yet again, an overseas indigenous population made it into the mainstream, but only in the role of “alien”, because that’s exactly what they are to their Western designers: alien.

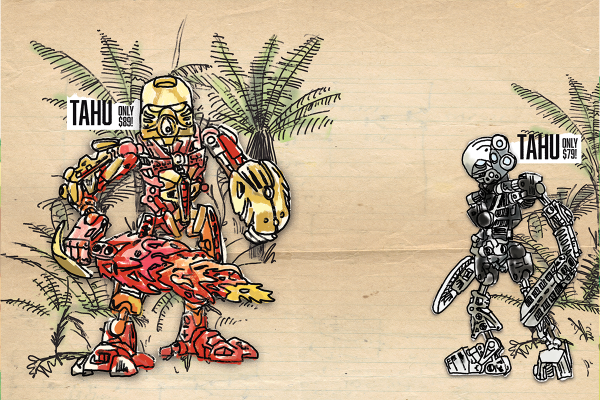

Let’s look at the original line of toys:

We’ll start with the lowly villagers, which were originally called Tohunga. There was Onewa, the grey one from the mountains (whose name literally just means “grey”). Matau, the green one from the forest who was maybe meant to be from the ocean because his name means “fish hook”. Did someone accidentally swap the two? Who knows. And how could we forget Whenua, the one that drills through the earth? Pronounced, of course, “wen-ua”. Which I guess is fine if you’re from Taranaki (it was later changed to ‘Onua’).

Remember: the Tohunga are tiny, 40-ish piece play sets. If you wanted a bigger toy, you had to purchase a whole different playset: the Toa. Also known as the Toa Mata (literally “mask warriors”) and later Toa Nuvu, these elemental heroes gained their power by adopting various masks. These came with new names, giving us Tahu (the fire Toa), Pohatu (the stone Toa) or Kopaka (the ice Toa). Each name is literally just their elemental theme in te reo. Other names came from other Polynesian languages, like the Hawaiian “Lewa” giving its name to the air Toa. Oh, and spoiler alert: if you knew te reo, you’d realise that island of Mata Nui (“Great Face”) was secretly the protruding mask of the sunken deity all along. Plot twist!

And it goes beyond names and places. The Matoran language - which is a fully-fledged thing of its own - has a sentence and grammar structure extremely similar to te reo, with a limited vocabulary made up of a hodgepodge of words from the Polynesian Triangle. And since people are so incredibly invested in Bionicle lore, a whole generation of kids in the early 2000’s ended up accidentally learning rudimentary te reo in the process of playing with these toys. No joke! The 10-part documentary series that I tried to watch (different than the one our volunteer watched) was hosted by a bespectacled geek with about a bajillion Bionicles on the shelf behind him, and at one point he interrupts the video to describe the naming conventions of the various Toa, explaining how the descriptive terms come after the nouns, all in perfect te reo. This man literally taught himself te reo without realising it.

Not every word was ripped from te reo; many just sort of “sound like” they’re Māori. LEGO also seemed to favour the same sounds over and over, undoubtedly confusing parents everywhere when they couldn’t remember if their kid wanted a new Brutaka or Piraka. Or was it a Berocca? But if you look past the early years of Bionicle, you’ll notice that a lot of these Pacific terms seem to die off, replaced with names that just sort of “sound like” they’re from here, or names inspired by Greek, Latin or other European sources. And there's a good reason for this; after the 2001 release of the ads, local iwi caught word that some Danish toy company was making products using their language, and they had a problem with that.

It’s at this point that a lawyer sent a strongly-worded letter to LEGO, basically saying, “Hey can you please not use our culture for this, also don’t you dare trademark any of these words.” And his challenge worked. LEGO apologised and said they’d change some names in the future, most importantly “Tohunga”, which translates to something much more influential than just “villager”. This was worked into the storyline by having the various Tohunga realise they’re one people and suddenly deciding to change their species name to “Matoran” - though this event was pretty quickly dropped from the story and pushed under the rug. The elder villagers were renamed “Turaga”, a clear nod to Tohunga. But this wasn’t the only thing pushed under the rug: the online game had a few lines of dialogue that needed to be changed. For instance, mentions of “Rangi and Papu” were removed, and Jala, the Captain of the Guard, became “Jaller”. He also no longer describes his participation in “the Great Haka dance” because… yeah.

LEGO, fearing a “bitter conflict” with Māori groups over their only viable product line, agreed to demands made by the iwi. The iwi, in turn, agreed that LEGO probably didn’t mean any harm by using Polynesian culture. Roma Hippolite (of the Ngāti Koata Trust) said at the time, “We have been impressed by the willingness of Lego to recognise a hurt was inadvertently made and show that in their actions.” LEGO sent a representative to meet with these groups in person, promising that future sets would avoid appropriation, and that an internal code of conduct would be built to avoid this mistake elsewhere. The next year, 2002, Aotearoa formalised Toi Iho Māori: the recognised trademark of te ao Māori – though, like the characters in Bionicle, it has changed shape over the years.

To make this even crazier, the lawyer that represented these groups would, years later, take on a much more high-profile case of misrepresented islanders. His name is Maui Solomon, and he is the guy that fought for formal representation of Moriori. Maui (Moriori, Kāi Tahu) has somehow been woven into this bizarre story, and despite what the Bionicle legends would say, he’s probably the real hero here. Sorry, Mata Nui.

Following the challenge, Bionicle made some retroactive corrections and changed their ethos moving forward. But the impact had already been made. An entire language and culture had been formed around these cultures, and a dedicated fan base sprung up to chronicle the lore - a fan base that is incredibly active online. Many of them are very aware of the influences of te ao Māori, but many casual fans never had a clue. And that was basically that: a bunch of white kids accidentally learned te reo, Maui Solomon got brought into the fray, and LEGO survived financial ruin by hitching a ride on Polynesian culture.

Now, we’re being treated to ads for an upcoming Bionicle game. Fans are veritably manic over this news, looking forward to a return to Mata Nui early next year. Perhaps we can look forward to a new generation of accidental te reo enthusiasts - though this time someone might want to tell them that the language is more than just flavour for a children’s toy.

LEGO is not the only group to tap Polynesian lore for “inspiration”. How often do we see te ao Māori cast as the “alien” culture, rather than human? Looking at you, Avatar. Each word appropriated a shadow over Polynesian culture. Each kupu not alien, just indigenous. Each set sold separately.

DICTIONARY SECTION BELOW - 1 PAGE�

A (Brief) Dictionary of Bionicle’s Polynesian Words

Yet again, somebody with a lot of time on their hands has come to the rescue. Chuckschwa on Reddit has compiled an extensive list of Matoran words and their Polynesian roots, some of which have been included here:

Characters

Toa - elemental heroes/protectors

Toa (Māori) - warrior, courage, champion, bravery, expert

Tohunga - villagers

Tohunga (Māori) - revered village expert

Tahu - Toa of Fire

Tahu (Māori) - to burn, ignite, set on fire

Pohatu - Toa of Stone

Pōhatu (Māori) - stone

Kopaka - Toa of Ice

Kōpaka (Māori) - ice

Lewa - Toa of Air

Lewa (Hawaiian) - sky, air, atmosphere; to float, swing

Gali - Toa of Water

Gali (Kamilaroi/Gamilaraay) - water, rain

Galu (Samoan) - wave

Onua - Toa of Earth

Honua (Hawaiian) - earth, land, world

Fonua (Tongan) - the whole earth

Vakama - Turaga of Fire

Vakama (Fijian) - burn

Nokama - Turaga of Water

Waka ama (Moari) - outrigger canoe

Noka, Nokata (Fijian) - to tie up, make fast, a boat from going adrift

Noke (Fijian) - woven basket for collecting seafood

Nuju - Turaga of Ice

Nuju (Rotuman) - river bank; beak; mouth; to recite by memory/heart; spokesman

Nuju (Sudanese) - to lead, tend

Onewa - Turaga of Stone

Onewa (noun, Māori) - granite/basalt, short weapon made of stone

Whenua - Turaga of Earth

Whenua (Māori) - ground, land

Matau - Turaga of Air

Mātau (Māori) - to know, be certain of (noun) knowledge, understanding; fish hook

Mata'u (Rotuman) - carefulness, caution; to watch

Matau (Tahitian) - fear, dread; accustomed or used to a thing; fish hook

Makuta - evil spirit, Master of Shadow

Mākutu (Māori) - witchcraft, sorcery, spell or incantation

—

Masks

Kanohi - masks of power

Kanohi (Māori) - face, countenance

Pakari - mask of Strength

Pakari (Māori) - to be strong, sturdy, mature

Hau - mask of Shielding

Hau (Māori) - vitality; breath, air

Kaukau - mask of Water Breathing

Kaukau (Māori) - to swim, bathe

Miru - mask of Levitation

Miru (Māori) - alveolus (part of your lungs)

Mirumiru (Māori) - a bubble

Kakama - mask of Speed

Kakama (Māori) - be quick, alert, nimble

Akaku - mask of X-ray Vision

Akakū (Hawaiian) - vision, trance

Huna - mask of Concealment

Huna (Māori) - to conceal, hide

Huna (Hawaiian) - secret

Rau - mask of Translation

Lau (Tongen) - to talk, to converse, familiar discourse

Parau (Tahitian) - to speak, converse; the shell of the pearl oyster

Komau - mask of Mind Control

Mau (Māori) - to seize, to take hold of

Koma (Māori) - axe head made of stone

Mahiki - mask of Illusion

Hiki (Māori) - to lift up, carry

Mahiki (Māori) - to jump, leap, hop, vibrate

Note: this mask was worn by the air Toraga, Matau, which might explain the words used.

Matatu - mask of Telekinesis

Matatū (Māori) - to be watchful, to keep awake

Ruru - mask of Night Vision

Ruru (Māori) - owl

Aki - mask of Valor

Āki (Māori) - to encourage, challenge, incite; to beat, pound, throw down

Rua - mask of Wisdom

Rua (Māori) - hole, chasm, abyss (where heavenly bodies disappear before returning again)

Vahi - mask of Time

Vahi (Pascuan) - to pass (of the beginning of a season)

Vahi (Rotuman) - to be completed; to be past/gone by (events, time)

—

Places and Nature:

Mata Nui - island home; Great Spirit

Mata (Māori) - face, eye, surface

Nui (Māori) - to be large, many, great

Koro - village

Koro (Fijian) - village

Mangaia - great volcano

Maunga (Māori) - mountain

Daikau - carnivorous jungle plant

Dai (Fijian) - trap

Kau (Fijian) - plant

Hikaki - large fire lizard

Hika (Māori) - to rub violently (to kindle a fire)

Kahu - great hawk

Kāhu (Māori) - hawk

Tarakava - giant water lizard

Tarakuero (Pascuan) - a fish

Tarakona (Māori) - dragon

Vatuka - stone monster

Vatu (Fijian) - stone

Ka (Fijian) - thing

Amaja - story circle

A'maja (Rotuman) - to develop a story/theme

Ignalu - lava surfing sport

Ignis (Latin) - fire

Nalu (Hawaiian) - wave

Suva - Toa shrine

Suva (Fijian) - mound or pile of stones used to mark a place; Capital of Fiji