Life in the ‘student city’ is a point of debate, disgust, and drama across the country. From falling off roofs on St Patrick's Day (which traditionally starts at 6am) to law camp scandals, endless Student Health AA referrals, flat initiations, the dying art of couch burning, and, of course, the infamous Castle Street riots… there’s a lot to unpack.

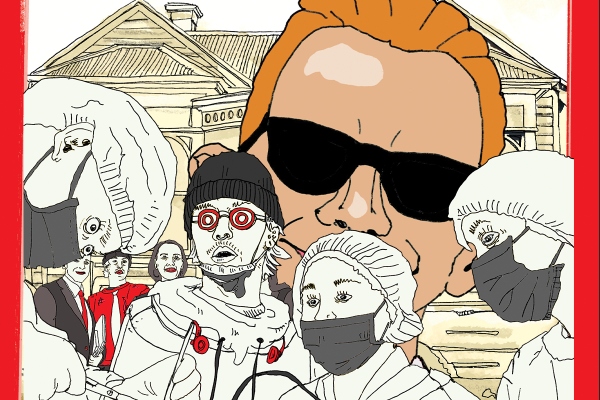

The media regularly describes student behaviour as “chaotic”, “out of control”, and “wild”. Last year’s documentary video by the Department of Information is a testament to this fascination. But even in its quieter, less sensationalist hours, North Dunedin holds down its reputation with ease. As the stereotype goes: the flats are cold, the students are bold, and the reputation is old, old, old.

As New Zealand’s oldest university, Otago has long had this particular image, even if it is only a minority of students contributing to headlines. In the 1890s, public graduations were cancelled after students kept showing up drunk and yelling abuse at guest speakers. This drunken, menacing vibe has extended to modern times. In 2004, National MP Sam Uffindel’s Dundas Street flat was declared a health hazard after competing in a contest for North Dunedin’s grossest flat, with his alleged behaviour being fuelled by “drug and alcohol abuse” according to an ex-flatmate. Uffindell “enjoyed” what he described as the “Otago lifestyle” after attending King's College, a decile 10 private school. But his choice to live in faux poverty is far from unique. For many of us in studentville, it’s a sort of rite of passage. To subject oneself to warzone-like conditions is almost a badge of honour.

Sometimes, media coverage of this “tradition” can overshadow the gap between those who (very temporarily) choose to live like this, and those who were born into it.

New Zealand tertiary education has always been riven by class inequality. This was cemented in our system when the free education access that baby boomers enjoyed was reversed after the fourth Labour Government introduced university tuition fees in 1989. An internal report carried out last year by the University’s Strategy and Analytics Office found that 60% of first years come from decile 8 - 10 secondary schools (a decile 10 school has a catchment area in the wealthiest 10 percent of the country). While decile 10 schools contributed 24% of students, only 1% of students came from decile 1 schools. If Otago was a perfectly egalitarian institution, each decile would be represented by 10% of students. The reality, however, is that undergraduates are 24 times more likely to come from schools located in the 10% wealthiest areas of the country than from schools located in the poorest. The reasons behind this are a whole article in themselves; what matters here is why that class of silver-spooners are walking, talking, and acting like they’ve come from nothing. As if poverty was inevitable.

When picturing the breatha lifestyle, Deathstar is one of the first examples that comes to mind. A complex of 26 boys joined by the aptly named ‘Methstar’, the flat’s reputation as a feral party hotspot is deserved. The current tenants were very gracious, welcoming me into where they’d all gathered on the sofa. Outside, the flat looks like a Soviet-era bunker. Inside, the boys were playing a golfing video game.

While the complex’s reputation conjures up images of glass shards and a frigid atmosphere, the living room was in a much nicer state than expected. The boys answered my questions with genuine consideration in between bouts of piss-taking banter directed at one another as they passed the controls.

Monty, Seb, Adam, and Will were joined by their two friends and fellow Castle residents Xavier and Tom. They took turns introducing themselves and discussing their backgrounds. Monty’s mother helps out with a vineyard and works as a wellness instructor, while his father is the head of a company, though he doesn’t know which (“you sound really close to them”). Seb’s father is a pharmacist, his mother a barrister (“not ‘barista’ mate. ‘Barrister’, you fucking twat”). Adam’s father manages a scaffolding company and his mother used to teach, but now doesn’t work. Will’s father runs online businesses and his mum doesn’t work either.

All came from King’s College and are in their second year of Commerce. The group are a near mirror-image of each other when it comes to their backgrounds, prompting Xavier to joke he experienced the “hood life” in comparison to his friends because he went to public school and is eligible for student allowance. None of the Deathstar tenants are eligible for an allowance, with Seb, Will, Monty, and Adam all maxing out their student loan and using savings to pay their bills. They said that the other two tenants, who weren’t there at the time, are financially supported by their parents.

Generations of breathas have not-so-gently passed down Deathstar to one another, furnishing the flat with additional destruction every year. In 2020, one group of tenants racked up $34k worth of damage, including boarded up windows and holes in 19 separate walls (that allegedly had been vomited into). It’s also rumoured by another source that, in the same month, a group of tenants were left unable to shower due to the shower head being ripped off and received a near $1k power bill primarily from stereo speaker use.

So why would anyone who has the means to live in far more comfortable conditions choose to live in the most infamously rank flat on Castle Street? This is something that baffles Zahoor, a second-year Neuroscience student and refugee: “Of all the people I’ve met in my life [from] different parts of the world, I don’t think any would want to downgrade. To start living in a place where there's no shower, broken glass… It makes no sense to me. I guess they want to experience what poverty is like.”

Zahoor is one of the few students at Otago who knows true poverty. Though he identifies as Afghani, Zahoor grew up in Pakistan until he was thirteen. “In Pakistan I had a wonderful life, I had everything,” he said. “But then I lost it.” As a Shia Muslim, Zahoor became the target of extreme sectarian violence and was forced to escape to Indonesia before being selected to come to New Zealand as a refugee. “The fact I got a scholarship from the University of Otago, I consider myself very lucky. If I don’t make good use of my time while I study, I can’t call my parents.” He said that couldn’t ask them for a loan to do another course, for example, while others “have a safety net underneath them if something goes wrong, tons of opportunities. Whereas I don’t have that many opportunities.”

Zahoor explained that when he was a refugee in Indonesia, there was no education. “I lived in a limbo, I did nothing for five years. It was a very harsh life. I don’t fear anything in life, but [the one thing] I do fear is ending up where I started. This is all I have. I have to make the most of it.”

Though he doesn’t drink and party, Zahoor said that even if he wanted to, he wouldn’t be able to afford it. Though he doesn’t see the appeal of Castle Street anyway. “Here’s the thing: Castle Street is the only street in the whole of New Zealand I’ve been to that reminds me of a third world country,” he said. “That’s the only street, every time I walk in I’m like, okay, am I in Pakistan, Afghanistan, or Indonesia?”

Back in Deathstar Seb admitted that the flat was the boys’ last choice on Castle: “In all honesty, we were late signing compared to most flats here, but they made us a pretty good pitch.” The property manager’s pitch included multiple renovations including fixing the floors, walls, and the front yard’s ‘mudpit’ - an infamous collection of moulding couches, trash bags, litter, and glass shards that was paved over last summer. “The boys before us, they absolutely fucked up the place. We were mates with them and saw what they posted on their stories, destroying walls and shit. There was so much damage, we were hoping it would get renovated and it did. Not fully, but it did.” It’s an improvement, said Will, even if the bedrooms are “still pretty shit.”

Still, for this life of pseudo-squalor, the boys pay $185 a week. They also forked out over $4.6k for a bond with a high risk of not being seen again, though they’re committed to doing their best to keep it. Seb explained that it’s not that they wanted to live in a disgusting flat; it’s for the experience. “Our mates in Christchurch, they have the nicest houses but not the proper experience, you know? That’s not what we’re [in Dunedin] for.”

Part of this experience is the annual tradition of last year's tenants returning to Castle in O-Week on the night of the Deathstar host, which had the theme of ‘pimps and hoes’ this year. “They were pretty respectful to our flat, because they knew us,” said Monty. “But the others… they broke windows, doors, punched holes in the wall. It's because they’d already been through it themselves and so, in a way, it was our turn.” His tone hinted at a passive acceptance of this ‘old boys’ mentality and the hazing behaviour that comes with it.

When I asked what their parents thought of their decision to sign Deathstar, Seb said his understood perfectly well: “They came from Otago themselves, lived in Dunedin. They’ve been through it. They understand. I didn’t really have a choice [to come here], it was kind of like this is the place to be.”

“It's a stereotype that you’d come from a nice place, a private school, and want to keep experiencing that lifestyle,” Monty said. “The fact we’re from there means we want to experience different aspects of life.” Xavier agreed that it's a rite of passage, saying he couldn’t care less about the quality of a flat as long as there’s a bed, kitchen, toilet, and shower (“shower’s pretty fucked, though”). “For a couple of years you live like shit, it's good fun.”

“You come down here, obviously in your halls, you see everyone else doing it, hear everyone else doing it,” Seb added. “If you're in Dunedin, if you like partying, this is the place to be.” Another one of them chirped that someone in the circle dropped $300 last week on a night out. I asked what they spent it on and was met with some wry chuckles.

But not everyone else is doing it. Zahoor sure isn’t. Does his abstinence from partying and drinking ever make him feel isolated from this “university experience” the Deathstar boys speak so lovingly of? “As far as student culture: am I excluded? Am I included? I don’t give a damn about it, with all due respect,” Zahoor said. “I think people are different, that’s all. It’s not like I feel bad about myself, I’m actually proud of it. It’s a different thing when you accomplish everything on your own.”

Self-sufficiency is something Zahoor regards as ideal at this age. ”I don’t call my parents and ask them for financial support at all, I try to be independent. That’s what university life is all about, right? That's the thing, a lot of you guys came to Dunedin from different parts of New Zealand so you can be independent. If you’re calling your parents for support to fund your lifestyle, you’re not really independent, are you? When you come from a background like me, you tend to work a little bit harder,” he said with pride.

“I don’t think if [my circumstances] were any different it would have been helpful for me.”

Though he’s no stranger to it, party culture wasn’t at the forefront of Nikau’s* decision when he picked Otago; scholarships were. The son of an ex-kindergarten teacher and a war veteran on a medical benefit (who helps at-risk youth), Nikau is one of the first in his family to attend university. Having not been offered any scholarships to Lincoln University, his next choice was Otago. Here, his passion for rugby led him to pursue a degree in Sports Development and Management. Coming from a decile 4 scholarship-based boarding school, Nikau didn’t consider anywhere in the North Island, wanting to get “as far away from there as possible.” He described the home lives of many on the East Coast, where he grew up, as “real rough”. The young people his father comes into contact with are often being impacted by domestic violence and substance abuse.

His fresh start at Otago, however, came with unexpected challenges. Nikau, who is of Ngāpuhi and Te Whānau-ā-Apanui descent, describes the culture here as “pretty white-washed” where he felt harshly judged by the mostly Pākehā upper-class peers he was surrounded by.

“I haven’t found much of my culture down here, so I felt out of sorts a bit. Down here no one speaks the way I do, no one acts the way I do. ‘Cos, for me, I casually walked around in singlet and gumboots and whatever. I saw no one else wear gumboots around town. I speak like a stereotypical Māori, and people judge on that because they think it’s hori. Just things I do that would be a normality back at home,” he said. “They have their own sort of world.” This world, of course, is filled with binge drinking, a culture he described as “black out until you tap out… pretty much half of my hall would be drinking from Tuesday to Sunday.”

On one fateful night, coming back drunk from the rugby club, Nikau went to a function at a nearby flat that was hosted by returning students from out of town. At the party, Nikau bore witness to a tradition that centred around a sort of hazing ritual. “It was really weird,” said Nikau. “I guess you can expect it from Dunedin culture and how it goes way back… all the traditions and stuff. They’ll be giving you shit, yelling slurs in your ears, pouring drinks on you, stealing.”

The trigger point for Nikau was the continual pilfering of his drinks. It began with one girl stealing out of his crate: “I was like, ‘Nah. that’s not on’ and got it back while I walked through the line.” Shortly after, a group of boys stole two more, resulting in an argument. He told them,“Give me back my drinks, I didn’t take yours. I know what it’s like, but treat people with respect although we’re freshers and stuff.” After getting his drinks back, they were stolen a third time — this time the entire crate. “I was like, ‘Can I have that back?’ trying to talk with him nicely, he was being really aggressive.” Then an argument broke out.

The events of that night resulted in Nikau receiving an alcohol ban, which he was then caught breaking when he dropped a bottle in front of a security guard. A third strike resulted in him getting kicked out of his hall - though it’s not quite as simple as it seems. Halls at Otago don’t exactly jump at the chance to kick out students and, in this case, the hall in question tried to help set up a chain of support for Nikau.

“I wasn’t just pissed off one night and wanted to hit someone. It was all the things that were going on prior that influenced and led to my behaviour, and the behaviours of others as well.” Nikau explained that those were the conversations he had with the Heads of College. His frustrations weren’t with the hall, but with wider Dunedin drinking culture. “I don’t have any beef with them at all, legit, cos they looked out for me. But it's the environment I was put into in the first place, I guess,” said Nikau. “Like alcohol for first years, [it’s] mad.”

After getting kicked out, Nikau’s hall arranged for him a motel for two nights. Struggling to afford food, he asked the motel to charge the college, becoming further in debt to them. After this accommodation lapsed, Nikau found himself homeless at nineteen, sleeping in the backseat of his car at the top of Signal Hill and stealing food from supermarkets while trying to hold down a hospo job. He could’ve stayed at his girlfriend’s place, but he didn’t want to burden their power bills or take advantage of rent. He could have called his family for help, but he didn’t want to burden them, either: “I had too much pride to even ask for help.” So he said he resorted to staying at a mate’s house. This lasted a month and a half.

“It brought [my grades] down so much. There were times when I didn’t even want to go to class because I was too tired from the night before.”

Isolation didn’t help. “All my family is back at home, all the people I could talk to were my mates, but they were on the same party vibe as me. You can’t really talk to a drunk person [about your problems]. There was nobody to give me any of that wisdom, that guidance down here when I was struggling.” He also attributes it to his pride getting in the way: “I didn’t want anyone to know.” So he didn’t tell anyone.

Wanting to make a change in his life, Nikau - in a sort of full circle moment - reached out to the Māori Centre who he said “helped out a lot”, offering him accommodation as well as counselling. There he reconnected with an old rugby coach and found a club where other Māori and Pasifika students go, which “feels like home.”

Despite having been at high risk of dropping out with all the “hardships and crap” he went through, Nikau said it’s never something he considered: “If I dropped out, I’d just be giving up. Waste of money, waste of time.” He currently works two jobs to pay his bills and tuition, planning to take five papers in semester two and three in summer school to complete his degree. “If had [their] lifestyle, if I was in his shoes, fuck, life would have been so much easier. Money can get rid of all your problems.” He admitted that “there’s a lot of that feeling of jealousy, not why are they here, but what are they actually trying to pursue?… I have to push more, work hard, get my head straight in the game so I don’t fuck up like, you know, getting kicked out.”

Getting kicked out would have meant that all of Nikau’s hard work would have been for nothing. It would’ve been the end of the line. A non-option.

But that’s not the case for everyone.

There’s an urban legend at Otago about a guy who wanted to get kicked out of his prestigious hall. They say he did all sorts of shit in the hopes of getting dropped. People usually joke about him, call him a legend, that sort of thing. From what we can tell, the story’s real. Only in real life, he ended up getting bailed out by his parents.

Faux poverty is all the rage. It’s a time of suffering, to look back on and say: “See? I did it. I did it, too.” But to be in the in-group, not only do you have to be able to withstand and enjoy the decrepit conditions, you have to be able to afford them. Faux poverty is a choice. An expensive one. And for all its presentation, it’s as much a mark of class as a fur coat.

*Names changed.