“Help! I need an adult!” I cry upon discovering that my lamp is still not turning on, even though I’ve replaced the bulb and tried it out on five different power points. No, you don’t need an adult, my self-affirming internal monologue says, you are an adult.

No one teaches you how to be an adult. There’s no sudden “a-ha” moment of realisation when you are crowned “Ms Adult”. Instead it is far more likely that you will gradually stroll through life’s perpetual light drizzle and one day notice how absolutely drenched you are. Being a “grown up” is all about perspective.

From the late and great author Maya Angelou’s perspective, adulthood is all a big charade. “I am convinced that most people do not grow up,” she wrote in Letter to My Daughter. “We marry and dare to have children and call that growing up. I think what we do is mostly grow old. We carry accumulation of years in our bodies, and on our faces, but generally our real selves, the children inside, are innocent and shy as magnolias.” Dr. Seuss had a similar opinion, saying, “Adults are just obsolete children and the hell with them.”

If some of the weirdest and most wonderful literary minds on Earth struggled to come to terms with being an adult, then it is little wonder that I find the thought of being “responsible” somewhat daunting.

As a frequent daydreamer and mind-wanderer, I often find myself zoning out in the middle of the day and silently pondering the complexities of life. Among these complexities regularly comes the dilemma of adulthood: Am I an adult? Do adults even exist? Legally, yes I am, but in every other aspect, hell to the no.

In an effort to better understand what being an adult is all about, I approached the most professional adults I could think of: my grandparents. Mavis and Roland Adams are both originally from Dunedin and have, between them, more than 140 years worth of worldly experience. They have raised three boys, one of whom turned out all right — my Dad. When asked about their experiences of emerging into adulthood, Mavis was quick to point out the differences between growing up “then” versus growing up now. “When Rolly and I both grew up, there were no such things as teenagers; they didn’t exist. Teenagers were an American invention from the mid-50s. When we left school to work, even though we might’ve only been 16 at the time, we were adults.”

Rolly, who attended Otago Boys High School, is a man who within the last year not only underwent hip-replacement surgery but also learned how to use Google. He has travelled the world, lived in a brothel and found solace in a ride-on lawnmower, and he spent his first ever pay (17 shillings and a sixpence — around $15 today) on a Morse key for his radio set. “His father nearly killed him!” Mavis says. “He was absolutely aghast that [Rolly] should waste his money when he was supposed to bring some home and pay for his board.” Responsibility for oneself came far earlier for our forebears than it does for many of today’s youth, but that doesn’t mean we have it easier. “I see what young people have to go through,” says Rolly, “and I sure am glad I’m not [one of them].”

Mavis states that she finds a person’s sense of responsibility to be equivalent to their sense of adulthood. “[Being an adult] is about having responsibility,” she says. “That’s what sort of wakes you up to the realisation that you’re a grown up; supporting yourself, no longer being dependent.”

Although this is my third year living away from home and my parents have relocated to a different continent, I still feel substantially dependent on them. Through carefully timed Skype calls and text messages, my emotional requirements are met via “Hello? Can you hear me? Hi! I miss you!” and “Goodnight/morning xxx” moments. If being independent means I can’t Snapchat my Dad a picture of my laptop screen with the caption, “HELP WHAT IS THIS?”, then honestly I don’t know if I want it.

I knew my adulthood dilemma couldn’t be something that I was suffering alone, so I decided to “take it to the streets”, as it were, to gauge how others feel about growing up.

Upon being asked the question, “When did you realise you were an adult?”, many people had to stop and think for a while. Sarah Thomas (19) said: “I’m not, but buying my own toilet paper for the first time came pretty close.” James Stevenson (32) said: “When socks for Christmas became exactly what I wanted.” Matt Hughes (25) said: “Somebody called me ‘sir’ at the supermarket. I had an internal meltdown and went home with a tub of hokey pokey just to prove I’m not [an adult].”

“It was Margaret Atwood who said ‘I believe that everyone else my age is an adult whereas I am merely in disguise,’” said Julia Reynolds (24), “and there are few quotes I feel I can relate to as much as I relate to that one.”

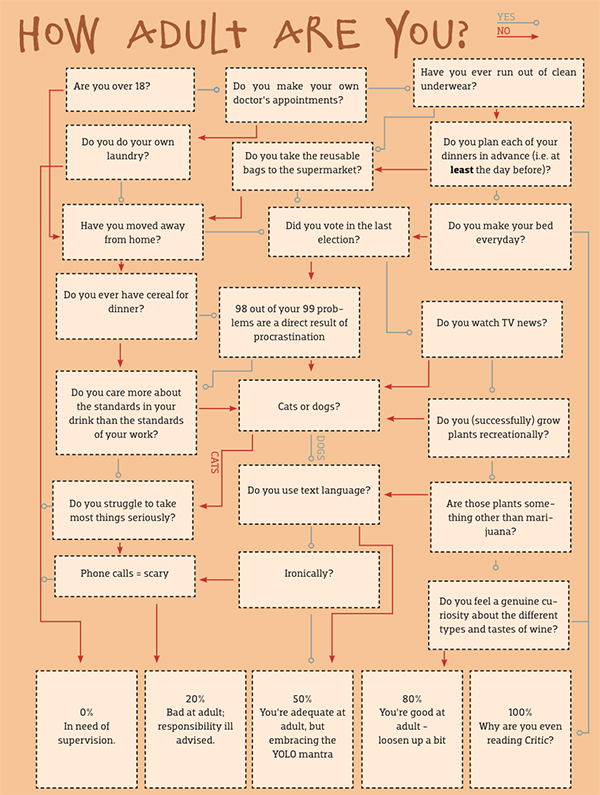

Taking into account the wisdom of both the consulted “professional adults” and the numerous members of society on the streets, I compiled a list of the ways in which I and people of my generation may or may not be properly functioning adults (this is, of course, in no way definitive).

Five Signs You’re Not Yet a Functional Adult

#1 You have no idea where your money goes, or you know exactly where it goes (see: alcohol and online shopping) and have no desire to accept or change this behaviour.

#2 Your inability to plan ahead means that you will often spend significant amounts of time doing nothing in particular. Although this may seem great at the time, it is unproductive.

#3 You don’t have a laundry routine and always seem to run out of clean underwear when you need it. N.B. Buying new underwear does not excuse you from the massive amount that still needs to be washed.

#4 You have several morning alarms set at 15-minute intervals, and you still manage to hit “snooze” almost every single time.

#5 You still call your parents to help fix everything and hope that they can make all your problems disappear.

Five Signs You Might Be Turning Into a Functional Adult

#1 You feel more accomplished after paying bills on time than you do after finishing an entire season of your favourite TV show in one day.

#2 You go to the supermarket before you’ve completely run out of food.

#3 You fold your laundry on a semi-regular to regular basis.

#4 You’ve stopped stressing out about accomplishing certain things by certain ages. So your three-year degree is taking four and a half years, so what? Keep doing you.

#5 You no longer feel the need to sugarcoat things when giving advice and/or excuses to friends (e.g. “I think you’re being an idiot, which is fine, and I don’t want to come out tonight because I truly, deeply don’t want to.”)

The blog Hyperbole and a Half is run by Allie, who uses both her artistic talents on Paint and her wonderful sense of wit to detail experiences from her life. One of her entries, “This is Why I’ll Never be an Adult”, fits in perfectly with the adulthood dilemma I am currently observing. She writes: “A few times a year, I spontaneously decide that I’m ready to be a real adult. I don’t know why I decide this; it always ends terribly for me.” Like my grandparents and the innocent bystanders I approached on the street, Allie agrees that adulthood as a concept is inherently flawed. Those of us on the precipice (see: anyone aged 18+) might struggle with the independent, responsible side of growing up, and as Allie puts it: “It is important for me not to surpass my capacity for responsibility. Over the years, this capacity has grown, but the results of exceeding it have not changed.”

Undoubtedly for many of you readers, the following scenario will be somewhat familiar: It’s the first day of Semester One, it’s a new year and you’ve promised yourself a new attitude towards studying. You attend all of your first week’s lectures, you’ve checked your tutorial and laboratory times don’t clash, and if you’re really on top of things you may even have done one of the assigned readings. The second week goes similarly well, and soon you’re so proud of your initial efforts that you think: Hey, I should treat myself for this — I deserve a break. Cue the beginning of the end. Henceforth comes the all-too-familiar period of procrastination with Game of Thrones binges.

The issue with this scenario is not the procrastination and responsibility-avoiding so much as it is the guilt-spiral associated with it — the idea that until you feel like an adult, you’re not succeeding. Why must we beat ourselves up so much for it? As the renowned philosopher, Hannah Montana, once said: “Nobody’s perfect! I gotta work it! Again and again ’til I get it right.” Being an adult involves accepting responsibility for the actions you make, accepting and growing from them.

Nobody walks into their kitchen, notices the pile of dirty dishes and gets excited about the thought of washing them. Household chores and responsibilities are generally very annoying, but as we grow older, our reasoning changes. When you were a child and your parents asked you take out the rubbish, you did it not because you wanted to but because you were told. Through your emergence into adulthood, however, you will take out the rubbish not because you have been told, but because you enjoy living in a house that doesn’t smell like a dumping ground.

If an adult is defined as someone who has fully developed into a functioning person, then can anyone really be an adult? There’s always room to grow. “I may be in my 80s,” says Rolly, “but I’m not the same person I was 10 years ago.”

After further examination, albeit in a fair amount of darkness, I deduce that the bulb and lamp are both fine, so it must be the power points stuffing up. The circuit board! With my phone’s light guiding the way, I find the circuit board and take a peek inside. Switch number 11, “power points”, is off. I switch it back on, and across the room my lamp comes to life. See? Who says I can’t do this adult thing?