It Began With a WANK

In 1984, Prime Minister David Lange declared New Zealand a nuclear-free zone, prompting the US to expel New Zealand from the ANZUS treaty and impose a number of trade sanctions. Soon afterwards, Lange took part in that debate at Oxford, delivering one of the most eloquent denunciations of nuclear weapons ever heard and attracting worldwide attention. The following year, French Secret Service agents bombed the Greenpeace flagship Rainbow Warrior, killing photographer Fernando Pereira. Two French agents, Alain Mafart and Dominique Prieux, were each sentenced to 10 years’ imprisonment. After France imposed trade sanctions, the New Zealand government agreed to let Mafart and Prieux serve their terms at a French military base. The frogs served two more years, and were then smuggled home.We didn’t know it at the time, but New Zealand’s anti-nuclear stance spared us from the world’s first “hacktivist” attack. In October 1989, the US Department of Energy and NASA computers worldwide were targeted by the WANK worm. WANK (Worms Against Nuclear Killers) was an anti-nuclear computer bug whose origins were later traced back to Melbourne. Machines that had been affected by the bug had their login screens changed to the WANK logo, with the legend “Your System Has Been Officially WANKed ... You talk of times of peace for all, and then prepare for war.” When the source code was examined, it was found that the worm bore specific instructions not to target machines in New Zealand.

The New Revolutionaries

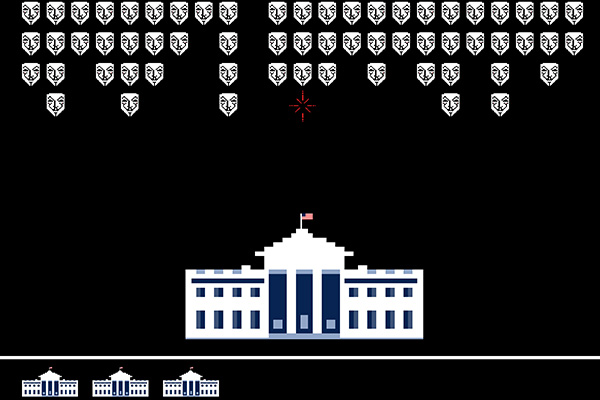

Hacktivism – a form of political protest, often militant, that uses computers and computer networks – has come a long way from these slightly puerile beginnings, and is now one of the major political movements of our time. Hacktivist ideology can take many forms, but for the most part hacktivists adhere to a libertarian worldview that emphasises antiauthoritarianism, human rights, privacy and pacifism. There are also more extreme anarchist and anticapitalist variants.The “Hacktivismo Declaration,” penned from 2000-2001 by members of hacktivist group Cult of the Dead Cow (cDc), reads in part “that full respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms includes the liberty of fair and reasonable access to information, whether by shortwave radio, air mail, simple telephony, the global Internet, or other media,” and “that state sponsored censorship of the Internet erodes peaceful and civilised coexistence, affects the exercise of democracy, and endangers the socioeconomic development of nations.”

In many ways, hacktivism represents the radicalisation of the Internet generation. It is the newest incarnation of the bookish revolutionary, the Lenins and Che Guevaras of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. This was echoed by Julian Assange in an April interview with Google executive chairman Eric Schmidt. “That’s the most optimistic thing that is happening – the radicalisation of the Internet-educated youth, people who are receiving their values from the Internet,” he said. “This is the political education of apolitical technical people. It is extraordinary.”

Hacktivism is also a peculiarly cross-cultural phenomenon, reflecting its twin roots in North America and Western Europe. It borrows the language of the US Constitution and the American preoccupation with freedom of speech and marries it to the revolutionary spirit of 1960s and 70s European counterculture.

In both of these regions, hacktivist ideals have begun to penetrate mainstream political discourse, from the iconoclastic Pirate Parties of Western Europe to the enthusiastic youth following of Ron Paul in the US (a following Paul himself never quite seemed to understand). In the movement’s first real electoral success, the Swedish Pirate Party won 7.1 per cent in the 2009 European Parliamentary elections, gaining two seats. Two years later, the German version gained 8.9 per cent in the Berlin state elections. And this year, the Pirate Party of Iceland won 5.1 per cent of the vote in the national elections, becoming the first Pirate party to win seats in a national parliament.

Trolls and Moralfags

The first wave of hacktivists in the 90s included groups like cDc, the Hong Kong Blondes and L0pht, and insisted on a strict ideological purity in their attempts to free data. This led the groups to condemn tactics like web defacement and Denial of Service (DoS) attacks. In 1998, when hacker group Legions of the Underground announced a cyberwar against China and Iraq in an attempt to disrupt those countries’ Internet access, a coalition of hackers issued a statement condemning the attacks.“We – the undersigned – strongly oppose any attempt to use the power of hacking to threaten to destroy the information infrastructure of a country, for any reason ... One cannot legitimately hope to improve a nation’s free access to information by working to disable its data networks,” the statement read. Following the statement, Legions of the Underground backed down. Oxblood Ruffin, a prominent member of the cDc, later praised the virtue of “civility” among hacker groups, and commented that “there isn’t a whole lot of difference between disabling a Web server’s ability to provide information – even if that information is distasteful – and shouting someone down in a town hall.”

Since the turn of the century, however, these principled, old-school groups have been largely supplanted by more populist movements, whose vocabulary does not contain the word “civility.” These new groups arose when 4chan’s infamous “no-rules” /b/ imageboard – described by Encyclopaedia Dramatica as “the asshole of the Internets” – overflowed and spawned the hacker collective Anonymous.

4chan in general, and /b/ in particular, often resembles a roiling cesspit of pure, unreconstructed mental diarrhoea. Users refer to themselves as “/b/tards” and each other as “fags.” Misogyny and racism, though often laced with heavy irony, pervades the site. Nick Douglas of Gawker.com affirms that “reading /b/ will melt your brain,” and the New York Observer describes posters as “immature pranksters whose bad behaviour is encouraged by the site’s total anonymity and the absence of an archive.”

Anonymous was first conceived as a 4chan meme, and the group itself coagulated during “Project Chanology,” a series of 4chan-facilitated attacks on Scientology websites in 2008. Composed of both politically motivated hackers (“moralfags”) and mere wind-up merchants (trolls), the group has employed DoS attacks and other forms of disruption to push its aims. In doing so the group has drawn the ire of Oxblood Ruffin, but whereas the old school still had cachet in 1998, Anonymous has far outgrown its forebears and has taken on a life of its own.

Lone Wolves

The hacktivist front line, however, consists of a very small and specialised group of computer geeks, and unlike the revolutionaries of yore, it is difficult to gauge how much popular support the movement actually enjoys.Oxblood Ruffin points out that “it doesn’t take a lot of people to change anything. It only takes one good programmer.” US telecommunications company Verizon recently released a report on security breaches that bears this statement out. The report shows that political activism lags far behind organised crime and state-sponsored cyber-attacks, accounting for around two per cent of all data breaches. When it comes to hacking, the main countries of origin are China, accounting for around 30 per cent of all hacks, and Romania, accounting for 20 per cent. However, as might be suspected, political activism is associated with much larger and more audacious data breaches.

This asymmetry – the ability of individual skilled hackers to wreak a disproportionate amount of havoc – works both for and against the hacktivist movement. On the one hand, it means online guerrilla campaigns can be carried out effectively with very few combatants, and it allows new heroes to spring up out of nowhere without having to negotiate the internal politics of activist groups. On the other hand, it also allows hacktivist tools to be used against the movement.

Significantly, counter-hacktivist “vigilantes,” such as The Jester, have the ability to significantly disrupt hacktivist organisations. The Jester is a highly skilled, pro-US government hacktivist who claims to have served in the US military. Since the beginning of 2010 he has targeted, with varying success, Jihadist websites, Libyan newspapers, 4chan, LulzSec, WikiLeaks and Assange.

In 2011, The Jester was responsible (albeit on the third attempt) for revealing the identity of LulzSec leader Sabu as Hector Xavier Monsegur, of New York. This led to Monsegur’s arrest in March 2012, after which he became an FBI informant and, in a major setback for the movement, turned in a number of leading LulzSec and Anonymous figures. As recently as July, The Jester claimed responsibility for a series of DoS attacks on the Ecuadorean stock exchange and tourism website, a reprisal for the country’s protection of whistleblowers such as Assange and Edward Snowden. He wrote that Snowden “is not a goddam [sic] hero, here to save Americans from ‘the government’ because of privacy infringements and breaches of the 4th amendment, he is a traitor and has jeopardized all our lives.”

The Jester has also threatened to take control of the fire alarms in the Ecuadorean embassy in London, in which Assange has been holed up since June 2012. If successful, this would force Assange outside onto UK territory, from which he would face potential extradition to Sweden on sexual assault charges.

An Uncomfortable Alliance

As The Jester shows, hacktivism can go both ways. The Jester also highlights the uneasy relationship between two of the movement’s core ideals – free exchange of ideas on the one hand, and individual privacy on the other. The Jester’s campaign against LulzSec was a campaign specifically targeted at breaching the members’ privacy and revealing their identities to the world.This tension between freedom of information and individual privacy is hardly new, and there are many examples of direct conflict between the two ideals – notably the 2011 News of the World phone-hacking scandal. Of the four legally recognised ways in which privacy may be violated – identity theft, defamation, publication of personal information, and encroaching on an individual’s seclusion or solitude – the latter three all come under direct threat from free speech.

For a group like Anonymous, whose very name invokes the notion of privacy, this might seem like an ill-thought-out marriage; a product, perhaps, of its members living their lives online behind carefully maintained, pseudonymous personas. For those who choose to live and communicate in the real world, total freedom of expression can be an oppressive force, enabling bullies and giving rise to an all-pervading surveillance.

On the other hand, this can also be seen as a particularly pure reimagining of the classical liberal idea of the public sphere. The public sphere, an area in which rights-bearing individuals can freely exchange ideas and debate political matters, was the dream of figures like John Stuart Mill. However, as the role of personality politics and the limits of human rationality became clearer, the public sphere came to be viewed with less of a rosy tint. The anonymity of the Internet, though, removes the problems around demagoguery: if nobody knows or cares who Topiary or Omega or The Jester are, we must focus instead on what they say. If the free exchange of ideas is hampered once personalities become involved, then the anonymity that the Internet offers can actually protect and foster that exchange.

When Edward Snowden, the NSA whistleblower, went public in the wake of his leaking of confidential documents, he cited personal safety as a reason: placing himself in the public gaze would make it harder for the US government to discreetly bump him off. As prudent as this step was, one unfortunate side-effect was to focus much of the media’s attention on Snowden himself – his background, his donations to Ron Paul, the girlfriend and six-figure job he left behind – rather than the leaks themselves. In the process, much of the outrage about what the leaks themselves revealed has been muted, and apathy restored.

Similarly, the impact of the Wikileaks cables became blunted amid fierce (but ultimately irrelevant) debate over the figure of Julian Assange. Assange became a lightning rod, memorably falling out with erstwhile ally the Guardian by being, on most accounts, a giant twat. Particularly regrettable was the aftermath of the Swedish rape allegations: the spectacle of so many otherwise liberal-minded Assange supporters becoming raging misogynists in an effort to defend their hero was extremely icky. But such is the nature of hero-worship, and of personality politics, and it’s easy to see why Anonymous want no part of it.

This Shit is Buzzy

Dunedin band Left or Right recently got a taste of hacktivism, when their website was taken over by a gentleman dubbing himself “Mr. Moro: Moroccan Hacker.” Possibly in the mistaken belief that Left or Right was some kind of political association, as opposed to a roots/metal groove outfit, Mr. Moro deleted the page’s content and replaced it with a picture of a masked Jihadi holding an assault rifle. “DoN’t YoU fEaR MR. MoRo Is HeRe,” he wrote beneath the image. “No PiTy, No MeRcY, No ApOlOgY, No sOrRy.”All of which goes to show that, however switched-on and politically savvy those at the forefront of the hacktivist movement may be, your average hacktivist is more likely some overexcited teenaged geek than a badass Che Guevara type. All the more reason to be nice to the nerds – to paraphrase Bill Gates, they will inherit the earth.