As someone whose major interest and study of art lies in painting, specifically in the safety and comfort of a wall-fixed picture that orders me to stand still and “read” what I’m seeing, I initially walked straight past the front-end exhibition Negative Space at the Milford Gallery as I headed towards the paintings displayed at the back. Only on my return to the front space did I begin to examine what was at first glance a simple exhibition of black wall-mounted sculptures on the gallery’s clean white walls.

Many members of the public may have admired some of Neil Dawson’s work but never attached his name to them. Neil Dawson, whose works are the feature of Negative Space, has iconic sculptural works displayed in Christchurch’s Cathedral Square and Wellington’s Civic Centre. These widely known works are the large spherical “Ferns” sculpture that hangs in Wellington and “Chalice”, which stood near the cathedral in Christchurch.

While many New Zealanders and tourists view these works as strong symbolic connections to these areas, very few would likely link them to Dawson, let alone compare these large-scale works to his smaller studio- and gallery-based sculptures. This is especially true of the works in Negative Space, with Dawson moving away from his previous approaches towards form, shape and line. Rather than creating the harmonic fragmentation featured in previous shows, Dawson’s works appear to displace the linear outlines of the sculpture, relating to their placement and position in space along with the perceived structural integrity of their form against the geometric contradictions they present to us.

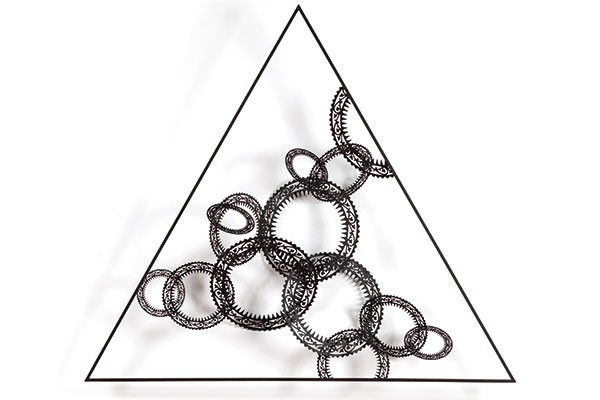

While these works are all wall-mounted and consist of black structures, three distinct styles separate them. The most numerous works are the “Black Halos”, which represent Dawson’s strongest application of space and his often prominent use of shadow. These halos, which have been modelled after sixth-century Spanish church designs, are positioned within thin metal frames shaped to appear as almost solid three-dimensional objects, receding and protruding according to the viewer’s position and the focus of their vision.

As well as this Esher-esque illusion of form, the halos seek to warp the perspective further through a complex series of interlocking loops and rhythmic patterning, which suggest they are floating in time and space. I saw in the Halos something similar to cogs caught in motion, which prevent the passage of time within the linear and structured frames. These works also manage to incorporate the white walls of the gallery into their illusion, with the flat background inhabiting the already ambiguous space of the works and acting like an aether, filling the form in a kind of two-point-five dimensional perspective. Shadow adds the final element, in what is described as the “spirit presence” of the works, reflecting our own experience and interaction within the wider space of the gallery, which is centred around each individual sculpture.

Along with the halo works, Dawson also plays with perspective in “Uccello’s Corner”, a wire-framed structure that seems rounder than it is in reality because of a combination of its mathematical precision and Dawson’s placement of the work. “Spike” is the most energetic of these works in its shapes and appearance. Its animated art style is reminiscent of his grand-scale 1994 sculpture, “Horizons”, and his 2013 show, Cloud 4.

In coming full circle, the sombre piece “Spirit” juts out of the wall in its own darkened area. It is modelled after the fallen Christchurch Cathedral spire, and its significance to Dawson is clear when related to his large sculptural work in the square. The piece seems almost spectral, floating outwards in the haze of black, defying gravity as the spire once did, but still presented horizontally, suggestive of its fallen state.

There is a lot to be taken from the exhibition Negative Space, both in surface considerations and in a deeper concern for our own position in art, but also in space and time. Movement and position are relative, so make sure you know where you stand.